Today we have photos and videos of Hawaii sent in by Rosemary Alles, with photography credits to both her and Hale Anderson. The text is by Rosemary and is indented; you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

Background

Sri Lanka lies in the shadow of her giant neighbor India; a teardrop on the vast slate of the Indian Ocean. My family emigrated from our island nation many moons ago, leaving a jeweled landscape ravaged by corruption, ethnic violence, and terrorism.

My first home in the West was in Canada and then on the Big Island of Hawaii. These days, I travel between South Africa and Hawaii centering my work around the protection of iconic mega-fauna.

Hawaii, like Sri Lanka, is home to a myriad endemic species; many are critically endangered, endangered or threatened. Frequently referred to as the “Endangered Species Capital of the World”, my island state is also home to Hawaii Volcano’s National Park. 344,812 acres of rainforest, desert and windswept magnificence that boasts at least one success story; the nearly flightless Nene Goose. (Branta sandvicensis). This once endangered bird has made a comeback thanks to ongoing funding and restoration efforts.

From Jerry: Here are two photos I took on the Big Island of a nene crossing sign and the goose itself: July 1, 2019.

Last month, my sister and I were on the Big Island of Hawaii memorializing my mother’s passing. While there, Kīlauea erupted, throwing molten rock 35-50 feet in the air. A shield volcano, Kīlauea is the youngest and most active volcano on the Islands. I’ve been close to many lava flows during my years Hawaii, and this time, we were -once again- fortunate to see Kīlauea erupt on September 15th, just hours before it stopped. A video is here.

Before we left, my sister to her home in Toronto, and I to South Africa, we sat by the ocean where the water meets the sand. That evening, as the sea swallowed the sun in a crepuscular ritual, the sky turned red, a fiery blood-orange I had never seen before, not in all my years on the islands.

Mālama ‘Āina. Take care of the land, take care of the sea.

Images of the fiery sunset have not been adjusted at all, other than for cropping.

These are the images of the fiery sunset:

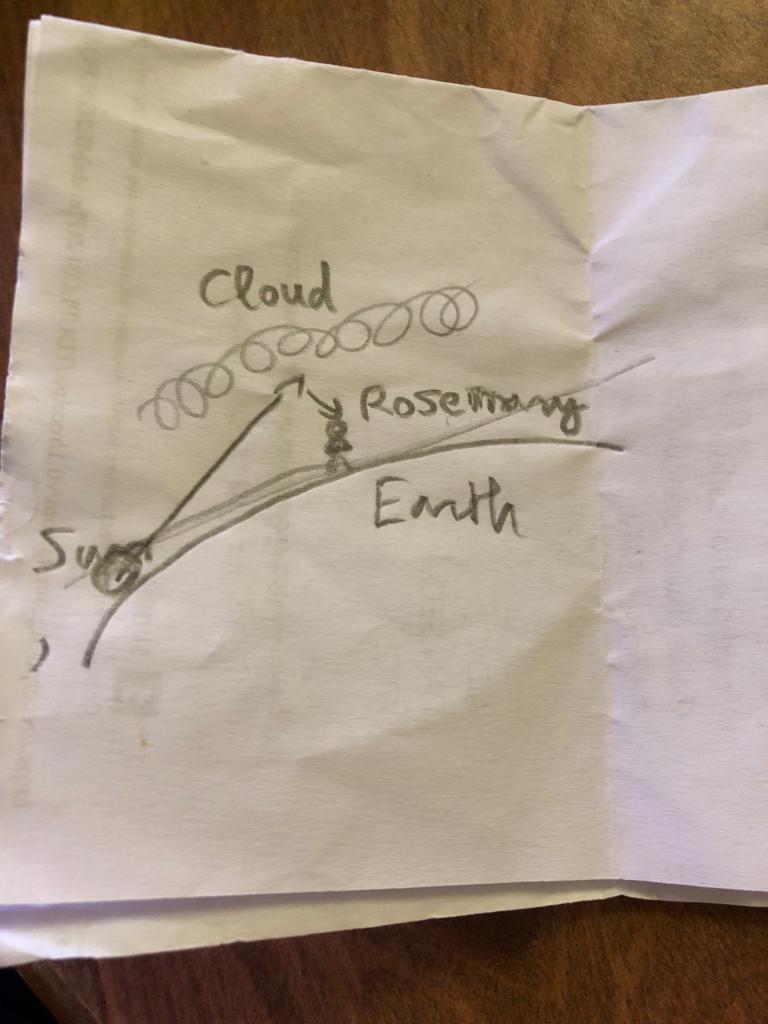

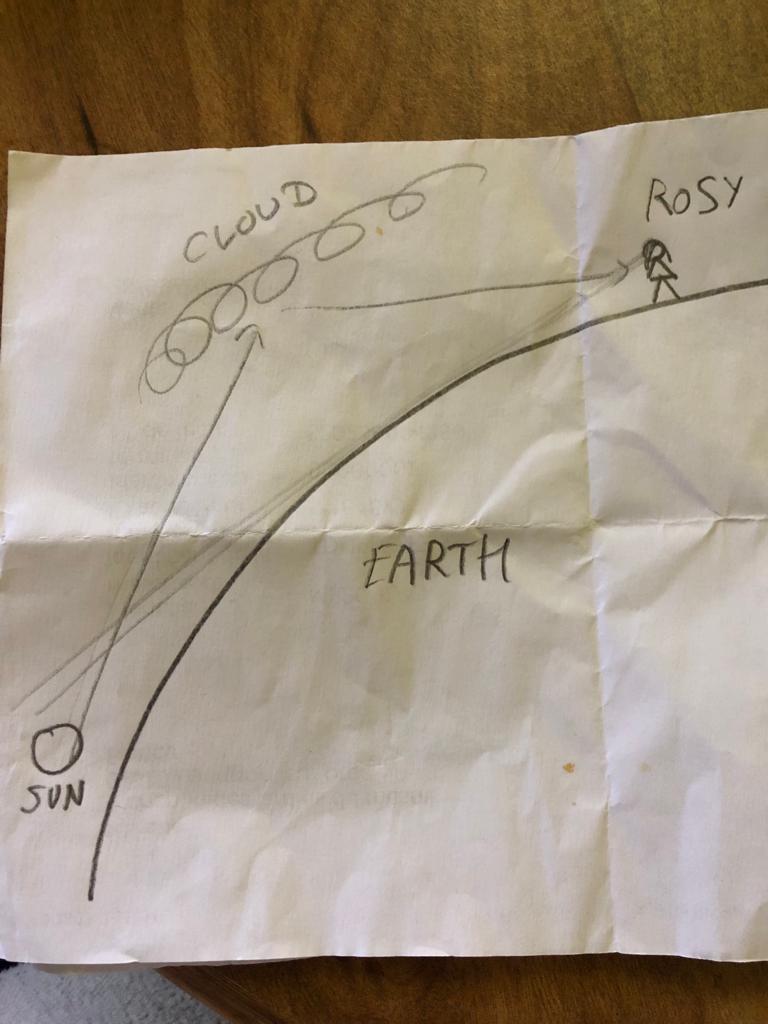

A brief explanation of the phenomena (the vivid nature of the sunset and the detail in the clouds) is explained as follows (by an astronomer-friend in France). Please refer to the two drawings obviously not drawn to scale.

Low hanging clouds are illuminated by the sun from below. The sun has set for the observer (me) but not from the perspective of the clouds. The grazing light enhances the contrast. Essentially the light from the sun is reflecting at a low angle on the clouds causing grazing.

The tree in the foreground of the eruption-image is an Ohi’a lehua (Metrosideros polymorpha). As of this writing, the species, endemic to Hawaii, is suffering from ROD (Rapid Ohia Death) from invasive fungi. Ohi’a is one of the first species to appear on “new” lava – once it has cooled.

Videos and text here: “Kīlauea was erupting at the summit most recently from September 10-16, 2023. Several roughly east-west oriented vents on the western side of the downdropped block within Kīlauea’s summit caldera generated lava flows onto Halema‘uma‘u crater floor, within Hawai‘i Volcanoes National Park. ”

“Halemaʻumaʻu is home to Pele, goddess of fire and volcanoes, according to the traditions of Hawaiian religion. Halemaʻumaʻu means ‘house of the ʻāmaʻu fern’.”

Kilauea after the eruption stopped:

Three videos of the 2023 Kilauea eruption:

” Their technical names are Anoetochilus sandvicensis (the jewel orchid); Liparis hawaiensis (the twayblade orchid); and Platanthera holochila. These native orchids grow in the very highest places within the island’s forests and bog.”

Orchids for my mother on the blue slate of the Pacific.

From this site:

“The Golden Pools of Keawaiki on the Kohala coast are landlocked freshwater ponds (anchialine pools) connected to the ocean. Lava fields surround them, and the only greenery is saplings growing at these oases. The Golden Pools of Keawaiki got their name from the gold-colored algae growing on the underwater rocks.”

Mauna Kea, the White Mountain, so named for the snow along its flanks during the colder months of the year. Mauna Kea is ~13,800 feet high.

Quote: “If we measure the entire mountain from top to its base, which is referred to as the ‘dry prominence’, Mauna Kea is 500 metres (1640 feet) taller than Everest.”

The observatory-domes of several world class telescopes are located atop the mountain; the W.M Keck Telescope, the Gemini, the Subaru, the CFHT (Canada France Hawaii Telescope), and the NASA infrared Telescope Facility are among the ~13 scopes on the White Mountain. I worked for both the CFHT and Keck Telescopes prior to switching career paths. The Thirty Meter Telescope (the TMT) was slated for completion prior to 2019, but was successfully halted after several years of protest by native Hawaiian groups. Hawaiian mythology considers the mountain “sacred”. In a tragedy for science, the compromise, if one is reached, may prove fatal for the future of astronomy on Mauna Kea, the world’s best site for ground-based astronomy.

Quote: “The height of the mountain, lack of light pollution, dry atmosphere, and minimal air disturbances make Maunakea the foremost place in the world for astronomy research.”

Quote: “Crucially, the MKSOA includes representatives from both astronomical observatories and Native Hawaiian communities. Its members say it marks a new approach, one that for the first time gives Native Hawaiians a voting role in overseeing the mountaintop. And although board members don’t want to get ahead of the process, an emerging compromise could see the embattled TMT built atop the peak in exchange for the decommissioning of several telescopes.”

Ironically, Hawaii’s coastline is also “sacred’ to Hawaiians, however, no clarion call has been issued to decommission the multiple hotels along the coastline. Connect the dots. Commerce and skill sets.

Mauna Loa, the Long Mountain, slightly less in height than Mauna Kea. Hawaii Volcano’s National Park lies to the south of Mauna Loa.