Today is part 2 of photos of a part in southern Africa from reader William Terre Blanche; this is the second of two installments (the first is here). His notes are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them. I begin by quoting his introduction from yesterday:

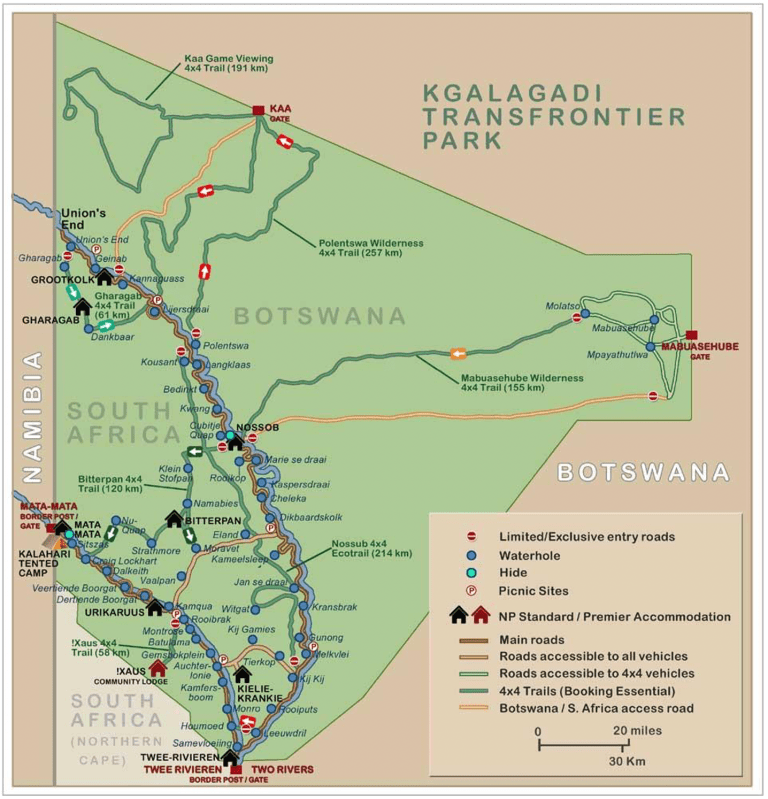

Here are some photos from a visit last year to the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park (Kgalagadi means “place of great thirst” in the San Language).

This vast wilderness reserve used to comprise two separate game parks, the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park (South Africa) and the Gemsbok National Park (Botswana) separated by an unfenced border. However, in a historic 1999 agreement, South Africa and Botswana joined forces to create the world’s first trans-frontier nature reserve, the Kalagadi Transfrontier Park. It covers an amazing 38,000 km², an enormous conservation area across which the wildlife flows without any hindrance.

The Park is famous for its magnificent black-maned male lions, as well as an abundance of raptor species, but the beautiful desert landscape and unique atmosphere is probably what draws most return visitors there (myself included).

In December 2023, I had the privilege of spending almost 2 weeks in the park, and these are just some of the many photographs taken there (apologies, mostly birds, again..).

Three-banded Plover (Charadrius tricollaris) These can often be seen using the typical plover run-stop-search method of foraging at any suitable body of water. The area had unusually good summer rains last year, and these pretty little birds were often seen:

Violet-eared Waxbill (Ureaginthus granatinus). An almost impossibly brightly coloured little bird, they are actually quite common in the Kgalagadi, but the vibrant colours never ceases to amaze me whenever I come across one of them:

Sociable Weaver (Philetairus socius). One of the most iconic sights of the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park is the massive communal nests of the Sociable Weaver. Colonies of up to 500 birds build these nests in trees, telephone poles and sometimes rock faces. The nests are built entirely out of grass, and each pair builds its own nest chamber:

Northern Black Korhaan (Afrotis afraoides). Their raucous kraak-kraak-kraak call is often heard long before they are seen! Spends most of the day on the ground, searching for food which is mostly insects and occasionally small reptiles:

Cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus). The world’s fastest land animal and Africa’s most endangered big cat. This female was presumably calling for the young, although I unfortunately never got to see them:

Urikaruus Wilderness Camp. There are 3 main “Restcamps” inside the Park, plus a number of so-called Wilderness Camps. There are normally well off the beaten track, and mostly only reachable by 4×4 vehicle. There are no facilities whatsoever at these camps, so you have to be completely self-sufficient during the time spent there:

Male Lion (Panthera leo). I spent a couple of nights at the abovementioned Urikaruus Wilderness Camp, and on the second morning was awakened at around 04:30 by a male lion roaring right under the room where I was sleeping (next to my car, in the picture below). This was at the same time exciting and terrifying, but one of the memories that will stay with me for life.

After a while he started moving away, and I was able to get a photograph of this magnificent animal:

Lioness:

Cubs. On another occasion I spotted a single female lion lying in the shade of the tree a small distance from the road. After a couple of minutes she started calling, and these two cubs appeared from a nearby bush to join her. I can only assume that she had hidden them there, and after determining that the area was safe called them out into the open.