Did you spot the horned “toad” this morning? Robert Lang sent two reveal photos; I’ve put them below. You can see how camouflaged they are!

Category: reptiles

Spot the horned toad!

We’re seriously low on readers’ wildlife photos, so I implore you to send in any good photos you have. Thanks!

If you know some biology, you probably realized that “horned toads” are not toads at all, but lizards (genus Phrynosoma). They are disappearing due to human incursion into their habitats and competition from fire ants, who displace the non-fire ants that are the lizards’ normal diet. But reader Robert Lang has photographed one for the “spot the” photo below. Robert’s words are indented.

We’ve had a relatively cool, wet spring in Southern California, but we’ve now had a series of warm days, which have brought out both wildflowers and wild fauna. The flora and some of the fauna will go into an upcoming Reader’s Wildlife Photos, but I wanted to share one sighting of a relatively uncommon creature: a Blainville’s Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma blainvillii), also called the San Diego horned lizard, but here in the San Gabriels, we’re rather far from San Diego. They used to be quite common, but a combination of rampant collection for the novelty trade in the early 20th century, plus changes in habitat (e.g., non-native ants pushing out the native species that they primarily eat) has reduced their numbers considerably. I’ve seen them occasionally on one particular ridge above Altadena, and was pleased to see one today. They have great camouflage for this terrain; can you see this one here?

Click the photo to enlarge it if you must, but try to spot it first. The reveal will be at noon Chicago time.

Readers’ wildlife photos

Today we have some photos from the Galápagos by Ephraim Heller. His narration and IDs are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

You have published lots of photos from the Galapagos Islands over the years. Here is my contribution to the genre. I took these photos on a March 2022 trip. They are divided into two classes first identified by Linnaeus: birds and non-birds. Each will be posted separately. First the non-birds.Galapagos sea lions (Zalophus wollebaeki). Sea lions use whiskers for social communication (from Chilling Seals):Sea lions, like other pinnipeds, have a highly developed sense of touch, which they utilize both in their aquatic and terrestrial environments. They possess long, sensitive whiskers known as vibrissae, which are dense clusters of sensory hair follicles. These vibrissae play a crucial role in the sea lion’s ability to navigate through their environment, locate and capture prey, and communicate with conspecifics.Research suggests that sea lions do, in fact, use their vibrissae to recognize each other. These whiskers are rich in nerve endings, allowing them to perceive even subtle tactile cues. When sea lions come into close contact, they engage in a behavior known as ‘whisker touching,’ where they gently touch each other’s vibrissae. This behavior is considered a form of non-vocal communication and is thought to serve as a means of social bonding and identification.Each sea lion’s whisker pattern is unique, similar to a human fingerprint, allowing for individual identification. Sea lions use their whiskers to recognize each other by comparing the unique pattern and structure of the vibrissae. This recognition process involves a combination of tactile exploration and visual inspection. Sea lions often nuzzle or touch each other’s whiskers to gather information about the individual they are interacting with.Furthermore, sea lions possess a specialized neural network in their brain known as the somatosensory system, which processes information from their vibrissae. This system allows them to discriminate between different whisker patterns, aiding in the recognition and identification of conspecifics.

Sea lion pup being cute. They are experts at this:

Nursing sea lion pup:

Galápagos green turtle (Chelonia mydas). Per Wikipedia:

A subspecies of the green sea turtle. The species’ common name does not derive from any particular green external coloration of the turtle. Its name comes from the greenish color of the turtles’ fat, which is only found in a layer between their inner organs and their shell.Since green sea turtles migrate long distances during breeding seasons, they have special adaptive systems in order to navigate. In the open ocean, the turtles navigate using wave directions, sun light, and temperatures. The sea turtles also contain an internal magnetic compass. They can detect magnetic information by using magnetic forces acting on the magnetic crystals in their brains. Through these crystals, they can sense the intensity of Earth’s magnetic field and are able to make their way back to their nesting grounds or preferred feeding grounds.

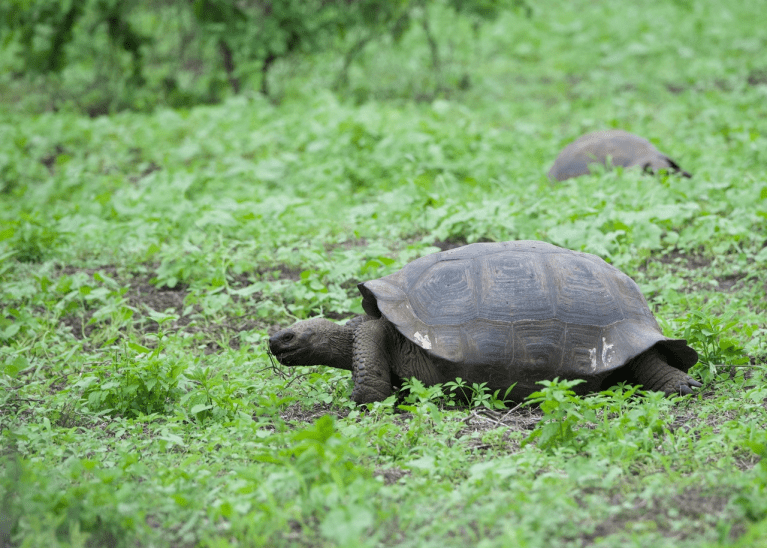

Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis niger). Per Wikipedia:

The species comprises 15 subspecies (13 extant and 2 extinct). It is the largest living species of tortoise, and can weigh up to 417 kg (919 lb). They are also the largest extant terrestrial cold-blooded animals (ectotherms). With lifespans in the wild of over 100 years, it is one of the longest-lived vertebrates. Captive Galapagos tortoises can live up to 177 years.Galápagos tortoises are native to seven of the Galápagos Islands. Shell size and shape vary between subspecies and populations. On islands with humid highlands, the tortoises are larger, with domed shells and short necks; on islands with dry lowlands, the tortoises are smaller, with “saddleback” shells and long necks. Charles Darwin’s observations of these differences on the second voyage of the Beagle in 1835, contributed to the development of his theory of evolution.

Galapagos marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). Per Wikipedia:

Unique among modern lizards, it is a marine reptile that has the ability to forage in the sea for algae, which makes up almost all of its diet.Researchers theorize that land iguanas (genus Conolophus) and marine iguanas evolved from a common ancestor since arriving on the islands from Central or South America, presumably by rafting. The land and marine iguanas of the Galápagos form a clade, the nearest relatives of which are the Ctenosaura iguanas of Mexico and Central America. Based on a study that relied on mtDNA, the marine iguana was estimated to have diverged from land iguanas some 8–10 million years ago, which is older than any of the extant Galápagos islands. It has therefore traditionally been thought that the ancestral species inhabited parts of the volcanic archipelago that are now submerged. However, a more recent study that included both mtDNA and nDNA indicates that the two split about 4.5 million years ago, which is near the age of the oldest extant Galápagos islands (Española and San Cristóbal).The different marine iguana populations fall into three main clades: western islands, northeastern islands and southeastern islands. These can be further divided, each subclade generally matching marine iguanas from one or two primary island, except on San Cristóbal where there are two subclades (a northeastern and a southwestern). However, even the oldest divergence between marine iguana populations is quite recent; no more than 230,000 years and likely less than 50,000 years. On occasion one makes it to another island than its home island, resulting in hybridization between different marine iguana populations.

Galapagos land iguana (Conolophus subcristatus).Charles Darwin personally disparaged these beauties as “ugly animals, of a yellowish orange beneath, and of a brownish-red colour above: from their low facial angle they have a singularly stupid appearance.” But what did he know, anyway?Per Wikipedia:Because fresh water is scarce on its island habitats, the Galápagos land iguana obtains the majority of its moisture from the prickly-pear cactus, which makes up 80% of its diet. All parts of the plant are consumed, including the fruit, flowers, pads, and even spines.The Galápagos land iguana has a 60 to 69 year lifespan.

Galapagos lava lizard (Microlophus albemarlens). Per Wikipedia:

There are seven species within the Galapagos lava lizard population and these species are found on several islands.The major defense mechanism used by these lizards involves dropping their tail; their tail continues to move and thus distracts their predators while the actual lizard will camouflage or flee.

Painted ghost crab (Ocypode gaudichaudii). I love the eye stalks.

Sally Lightfoot crab (Grapsus grapsus). Quite beautiful, IMHO.

Terrestrial hermit crab (superfamily Paguroidea). This individual seems very pleased to have his photo taken.

Readers’ wildlife photos

Today’s photos come from Bill Dickens of Florida. Bill’s captions and IDs are indented, and you can enlarge his photos by clicking on them. By the way, if you have good photos, send them along (see “how to send me wildlife photos” on the left sidebar).

Here are some wildlife photographs over the last couple of weeks around Cocoa Beach and the Kennedy Space Center.

I live a short walk away from Ramp Road Park, which backs onto the Thousand Island Conservation Area on the Banana River. The pier is a popular fishing spot and some of the local wildlife have cottoned on to the fact that humans are awesome fisherman and occasionally generous and willing to share unwanted catch. There is one Blue Heron and an ancient Wood Stork in particular that are very comfortable with proximity to humans.

The local power company, FPL, has installed Osprey nesting platforms over area transmission lines around town. There is a nesting platform a couple of blocks from me and I’ve been hearing the sound of hungry chicks for around 4 weeks now. There is a year-round population of Ospreys on the Space Coast and given the timing of these hatchlings, I would think they are part of the local population vs migratory Osprey.

I’ve been trying to photograph Pelicans diving for fish but a shot of them striking the water is elusive. It’s a challenging shot given the speed of their dive. So I’ll have to settle for now for the easier shot of them at the apex of their dive. One of these days I’ll get it.

I include a couple of shots of a Blue Heron and an Alligator from the Kennedy Space Center. As it’s a restricted zone, it serves as an important wildlife refuge. They are subjected to the surprise of a launch every few days. Everything vibrates, even miles from the launch or landing, however after initially startling they quick settle back into their lives.

Osprey (Pandion haliaetus) nesting platform:

Osprey on the nest:

Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) drying its wings on the Banana River:

Wood Stork (Mycteria americana) at Ramp Road Park:

Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias) at Ramp Road Park:

Great Blue Heron at sunset on the Banana River:

Brown pelican (Pelecanus occidentalis) diving for fish:

American Alligator (Alligator mississippiensis) at the Kennedy Space Center:

Great Blue Heron at the Kennedy Space Center:

Readers’ wildlife photos

Today’s photos come from Borneo courtesy of reader Daniel Shoskes. His notes are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

Just back from an incredible trip to Borneo. Just a smattering of the photos. Please forgive the lack of precision in species naming; I did my best to get the names from our guides.

First, a video of his whole trip can be seen here.

Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus):

Bornean Bearded Pig (Sus barbatus):

Silvered leaf monkey (Trachypithecus cristatus):

Flying squirrel climbing a tree (I have an amazing video of it gliding):

Macaque striking a Review #2 pose:

Sun Bear (Helarctos malayanus), smallest species of bear:

Proboscis monkeys (Nasalis larvatus):

Juvenile female, nose not as pronounced:

Green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) laying eggs and getting measured and tagged:

Newly hatched turtles about to be released to the sea:

Macaque mother and baby:

Crocodile with monitor lizard in its mouth:

Oriental pied hornbill (Anthracoceros albirostris):

Monitor lizard:

Black-and-red broadbill (Cymbirhynchus macrorhynchos):

Rhinoceros hornbill (Buceros rhinoceros) :

An insect eating bat (species unknown) curled up asleep inside a banana leaf:

Tiger leech (Haemadipsa picta). Amazing to see: when you exhale near them they lunge towards the CO2:

Red leaf monkey (Presbytis rubicunda):

Readers’ wildlife photos

We are in serious trouble, folks. I have about three days’ worth of readers’ wildlife photos left, and that feature (like “Caturday felids”, which has a dearth of readers) is in danger of becoming extinct. Please send in your good wildlife photos.

Today we feature ecologist Susan Harrison with some lovely tropical animals and one landscape photo. Her captions are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

Costa Rica Miscellany

Here’s the third and last batch of photos from a February 2024 trip to Southwestern Costa Rica, during which I visited a wildlife-rich field station on the Rio Sorpresa (Surprise River) and saw many colorful birds, both there and in the nearby Corcovado National Park and the towns of Golfito and Puerto Jimenez. Today’s photos mostly feature smaller and/or more subtly colored creatures from this trip.

Basilisk (Basiliscus basiliscus), also known as the Jesus Christ Lizard for its skill of dashing across water surfaces:

JAC: I’ve added this National Geographic video of a basilisk running on water:

Bright-rumped Attila (Attila spadiceus), whose distinctive song (“quit it, quit it, QUIT IT – aaaaah!”) is heard much more often than the bird is seen:

Panamanian White-faced Capuchin (Cebus imitator) looking angsty:

Charming Hummingbird (Polyerata decora):

Cocoa Woodcreeper (Xiphorhynchus susurrans):

Great Kiskadee (Pitangus sulphuratus), screaming its loud squeaky calls straight at me:

Green Iguana (Iguana iguana), a yard-long reptilian lawn mower:

Grey-capped Flycatcher (Myiozetetes granadensis) on Purple Mombin tree (Spondias purpurea):

Grey-capped Flycatcher on branch with Snakefern (Microgramma) epiphyte:

Common Pauraque (Nyctidromus albicollis), a member of the nightjar family, making its weird sounds:

Scarlet-rumped Tanager (Ramphocelus passerinii), which looks to me like a Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus) turned sideways:

Northern Tamandua (Tamandua mexicana), a large placid anteater seen in Corcovado National Park:

Variegated Squirrel (Sciurus variegatoides):

Yellow-green Vireo (Vireo flavoviridis):

One of the many waterfalls on the Surprise River:

Readers wildlife photos

Reader Divy Figueroa and her husband Ivan Alfonso, both of whom run an exotic-animal vet operation in Florida, also have their own menagerie. And today they are proud to announce the birth of two rare tortoises among the dozens that they keep at home. Photos and text (by Divy) are below, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

Forsten’s tortoise, better known as the Sulawesi tortoise (Indotestudo forstenii), is native to Sulawesi, Indonesia. Adults can reach between 10-12 inches. Ivan was lucky to see one in situ when he visited there several years ago, but, due to deforestation and mining, they are severely declining in numbers.

This baby hatched on January 30 of this year. He is the second baby hatched on our premises. Although the first was found in the pen with the parents, this one was incubated.

I placed him next to our first-born who was found in August of 2022, so you can see the difference in size. [JAC: a difference of about a year and a half]

Here’s a picture of an adult male (ours) for reference.

The last is a lagniappe I’m sure you’ll appreciate 😻 (JAC: It’s Jango, one of my favorite kitties!):

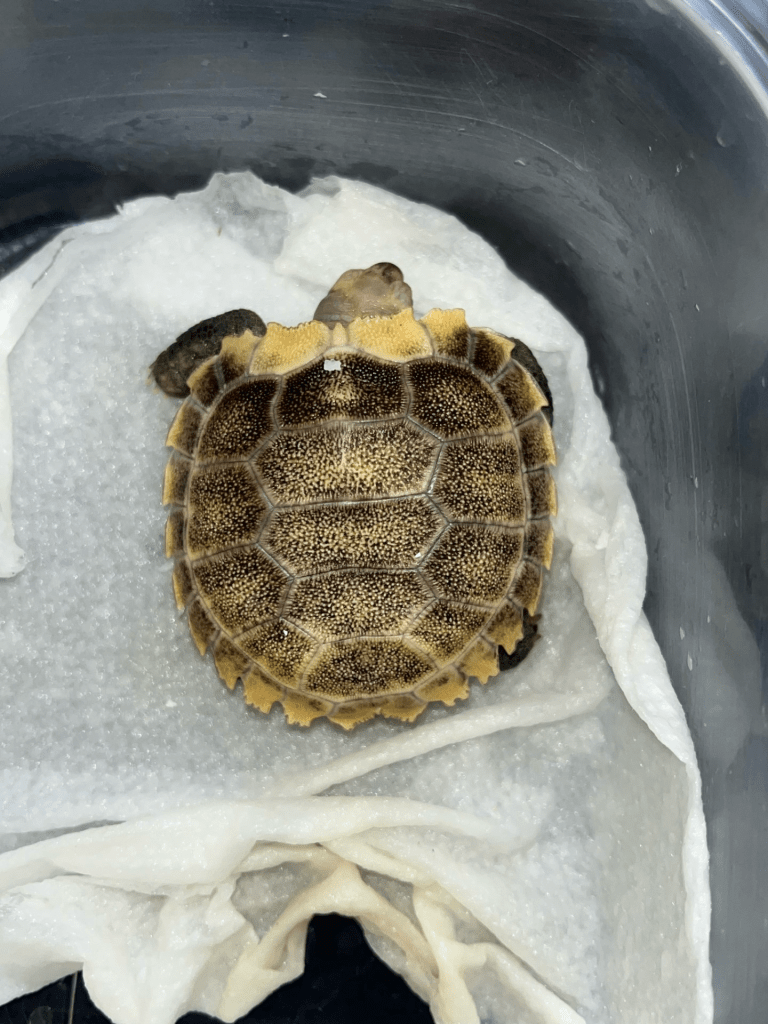

Here’s a newborn Heosemys spinosa, whose common name is the spiny turtle. They can be found all through Southeast Asia, though ours come from Sumatra. They are land dwellers, but like to be in shallow water. This is our first hatchling.

Notice how when fresh out of the egg, they retain the egg shape, but only for a while. They flatten out, and with their sharp ends, they resemble a ninja star. They lose this trait as they grow. Here is the baby in different stages of expansion, and an adult female for reference. This baby also hatched this January 30.

Readers’ wildlife photos

Please send in your wildlife photos! I have enough for a week or so, but the need is constant!

Today we have photos of Australian reptiles taken by reader Chris Taylor. His captions and IDs are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them.

I thought that I would share photos of some of the reptiles that I have encountered.

There are three orders of reptile in Australia: Crocodilia (crocodiles), Testudines (Turtles), and Squamata (Lizards and Snakes). I don’t encounter Crocodiles here, but the other two orders are well represented.

By far the largest order is the Squamata, and the photos here represent four of the families in the order. First of all, there is the Scincidae – Skinks, which are found throughout Australia, and one common species across much of Australia is the Blue Tongued Lizard, Tiliqua scincoides scincoides. This subspecies is found in the east and south of the continent. They are a fairly hefty animal, weighing up to 1kg (2.2lb). We encouraged them to come into the vegetable gardens by putting out pipes and rocks for them to rest in. In return they look after the garden by eating snails, slugs and insects. This particular individual has managed somehow to climb up into our old laundry room window, and doesn’t look happy the we are suggesting it might prefer to be outside again!

As its name suggests, they do have a bright blue tongue, that they use as a warning display, together with a loud hiss. But by and large they are very docile. There is another related species, the Blotched Blue-tongued Skink, Tiliqua nigrolutea, and this individual is demonstrating its warning display!

Cunningham’s skink, Egernia cunninghami. A closely related species is the Cunningham’s Skink. Smaller than the blue tongues, it is variable in colour, ranging from black to a brown that could be mistaken for the blue tongue. They are relatively common here. These were photographed in the Namadgi National park.

Eastern Water Skink, Eulamprus quoyii. Another skink that was common in out garden in our old house in the Hawkesbury Valley to the north west of Sydney, is the Eastern Water Skink. This is much smaller and lighter than the Blue Tongue, but we welcomed it into the garden as well because it helped to control insects.

The second family here is the Agamidae or Dragons. Whereas the skinks generally have smooth skin, the dragons are rather more spiky, culminating in the Thorny Devil (Moloch horridus). There are two species that I see often. First is the Jacky Dragon, Amphibolurus muricatus.

This photo is of an adult climbing up on a tree trunk used as a fence post.

The second photo is of a juvenile Jacky, that I saw outside my bedroom window while I was confined to bed for a while – though I was still able to take in what was going on around! This individual is very small – the pieces of gravel are only 20mm long, so that gives some scale. I suspect it was quite a recent hatching.

Australian Water Dragon, Intellagama lesueurii howitti. These are quite large animals, growing 60 – 100 cm in length, although the tail accounts for more than half of that. The photos were taken at the Australian National Botanical Gardens in Canberra. The first one has been fitted with a collar for tracking.

The second photo shows how long the tail is.

The third family is the Varanidae – Monitors. This includes the Lace Monitor, Varanus varius, which is often called Goanna, though this name is used for a number of different members of the Varanus genus. They do exist in my locality, though not on my property, preferring the rocky and tree covered areas to the open paddocks. But on a property that I used to own near Mudgee in Central West NSW, we would see them often. They are the second largest reptile in Australia, only the Perentie being bigger. They can be up to 2m long, and weigh as much as 14kg (30lb).

They have powerful claws that make them very adept climbers, like this one up the trunk of a eucalypt.

Finally, there are the Ophidia – Snakes. Canberra is often called “The Bush Capital” and as such snakes are found fairly regularly, even in the CBD. This includes the Eastern Brown Snake, Pseudonaja textilis. A very common snake around here. I have had a small number of them on my paddocks, and in the vicinity. It is a beautiful slender snake, and can grow to be 2m long. It is considered to be extremely dangerous, as the toxicity of its venom is surpassed only by that of the Taipans. They are also supposed to be very aggressive, although my few encounters with them have not proved this to be the case. Many years ago, I found that Tansy and Cinnamon, two of our goats, were lying dead side by side near their shelter. I didn’t investigate enough to truly determine the cause of death, but suspect that a brown snake was responsible for this. I encountered this one on a bike ride on a path only a few kilometres from the centre of Canberra. It is probably at least 1.5m long – the path is about 3m wide. I decided to wait until it crossed over before continuing on with my trip!

Red-bellied Black Snake, Pseudechis porphyriacus. The snake that I see most commonly on my place is the red-bellied black snake. It’s venomous, but no deaths have been reported from this snake. One of its food sources is other snakes, including the Eastern Brown, and anything that keeps them away is OK by me. Indeed, it is said although probably apocryphally, that if you have Red-bellied Blacks on your property then you will not see any Browns. They are docile, and I’ve even got up closer than I ever intended to one that was keeping hidden in a patch or pumpkin plants in the vegetable bed. I think I was the more surprised of the two of us. This first one had a home in an old hollow fence post that lay in the front paddock. We knew that it was there, and so were careful when we needed to work in the area, and gave it plenty of space. Here it is on a cold morning just outside its den, trying to get some sun to warm itself up. This is quite a dark morph of the snake.

The second photo is of a lighter morph, with almost orange belly scales.

Common Death Adder, Acanthophis antarcticus. Very rarely seen, in fact I’ve only ever come across one, is the Death Adder. The name probably derives from a corruption of “Deaf Adder”, which is how the first settlers in Australia referred to it. It is rarely seen because of its cryptic behaviour. It will bury itself in leaf litter and coil around so that the had and tail are close together. It will wait there for hours or days, and wait for its prey to come close and so ambush it. To help with this the last part of the tail is very much thinner than the rest of the snake, and it can use this as a lure. When a bird or mammal comes to investigate, the snake has to move very little to strike its prey. While it is in this position it will no move away even if one were to get very close, and so because of this was thought to be deaf. It is very venomous, but because it is so cryptic, few bites are recorded. This photo comes courtesy of my nephew Rich, who has made it a quest to find and photograph snakes!

Finally, there are the Testudinae – Turtles, including the sea turtles as well as land dwellers. This individual is of the Eastern Long Necked Turtle, Chelodina longicollis. This one is determinedly plodding down the drive to the front of my property. We had to wait for it to move before we could proceed down to the front gate, for fear of running it over, a fate that happens to too many of its kin, as they try to cross the roads around here.

Sometimes they just need a little hand to get them out of the road… Unlike some other turtles and tortoises, they don’t draw their neck back into the shell, but instead fold it sideways into the space.