Today we have an unusual group of photos from reader Rodney Graetz: an Australian landscape changing over 81 years. His captions are indented, and you can enlarge the photos by clicking on them:

One landscape: Interpreting 81 years of Change

Repeat photography is a widely used technique for recording landscape change. Its first use in Australia was in 1925 of a rangeland landscape (’Koonamore’) severely degraded in 1880-1910. I illustrate the landscape changes in a 10-image sequence spanning 81 years (1936-2017). My contribution was to digitize, enhance and align the photographic sequence, then note and interpret changes.

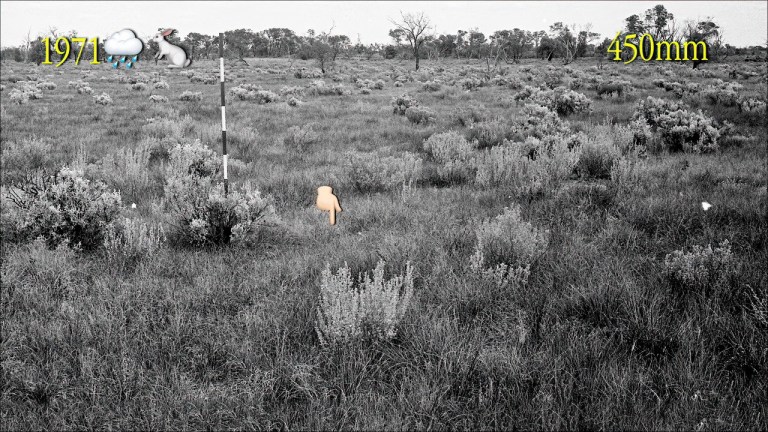

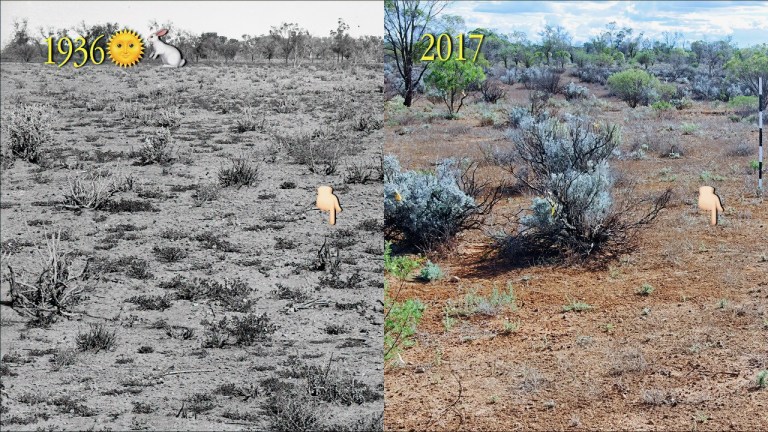

On the left hand side of each image is the year date, plus an emoticon indicating the seasonal conditions: the Sun (🌞) is below average rainfall, the Raincloud (🌧️) above average rainfall, and the rabbit (🐇) indicating high numbers. On the right hand side, is the rainfall in the 12 months preceding the photograph: the annual average is 200 mm. The fixed Pointing Finger is for soil surface changes:

A desolate landscape. In the 1860s, this was once a productive and valued rangeland. The original pasture plants were annual grasses and forbs, along with high-quality, palatable perennial shrubs. Grazing animals generated the degradation: sheep, and principally the uncontrollable, seething plagues of the introduced European Rabbit. The soil surface is now bare, and the clumps of sticks are the dead(?) remains of perennial shrubs. Scattered live perennial shrubs are visible in the near background. The question was ‘with no grazing, will this landscape recover?’ Sheep were fenced out in 1925, rabbits were eventually excluded, and kangaroo grazing was insignificant. In 1936, the inescapable conclusion was that after 11 years of no sheep grazing (1925-36), there were no signs of any response:

8 years on: The soil surface appears even more denuded and eroded but some of near and far shrub ‘sticks’ have resprouted a dense canopy of small leaves. These are ‘Bluebush’, unpalatable to sheep, and a last resort for rabbits. The resprouting was unexpected, but after 19 years of no sheep (1925-1944), but with ever-present rabbits, there appears little recovery. Perhaps there never will be:

14 years on: The last 12 months of rainfall was double the average (200 mm/year) and the landscape response is dramatic, regardless of the rabbit presence. The Bluebush shrubs are now leafier, and the areas in between carry a thick stand grasses and forbs, such as the daisies in the foreground. Now, the inescapable conclusion is that the seeds for all this new plant abundance must have been already present in the soil store and were triggered by the abnormal high rainfall:

21 years on: The dense stands of annual and ephemeral plants of the 1950 ‘wet year’ remain only as litter – fallen dead material on the soil surface. No bare soil is visible. This represents an ecologically significant transformation. The litter, or mulch, changes the functioning of the crucial soil surface, transforming a bare soil surface from one hostile to both seeds and rainfall, to one increasingly receptive to both. The uppermost layer of the soil is the incubator of all plant life:

35 years on: The viewpoint is correct, but the location of the sighting pole is not. The previous 12 months recorded more than double the annual rainfall. The two most obvious results are a dense standing dead layer of annual vegetation, interspersed with a number of now vigorous perennial shrubs. Before the arrival of sheep and rabbits, shrubs were the dominant layer across this landscape:

44 years on: The viewpoint and the sighting pole are now aligned. Colour: the landscape comes alive, and you can clearly recognise Bluebush. The pale green shrub is Saltbush (Atriplex species) in Australia, and its cousin ‘Shadscale’ in the USA. What was a field of dry, dead (?) sticks in 1936, is now a vista of Bluebush, with scattered Saltbush through preferential grazing. Both sheep and rabbits prefer the (high protein) Saltbush and ignore Bluebush. So, under with heavy grazing, ignored Bluebush eventually becomes more numerous than preferred Saltbush. Note the first appearance of a tall green woody shrub just under the rainfall figure:

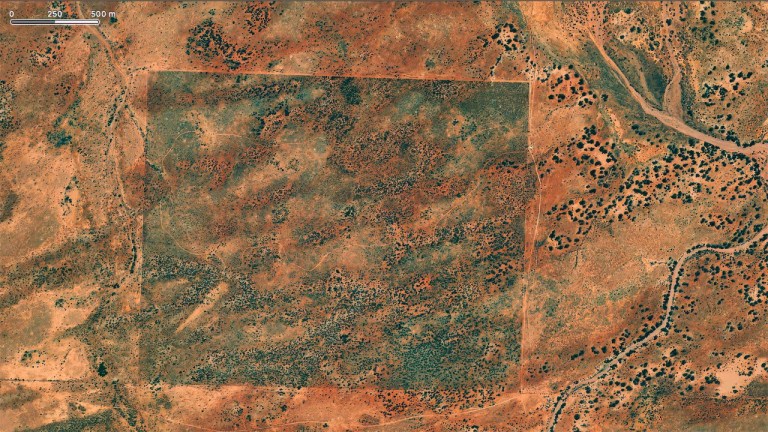

55 years on: The landscape is now visibly dominated by the two shrubs, Bluebush and Saltbush. Saltbush has increased in number while Bluebush has increased in shrub size, but not obviously in number. Numerous small and ephemeral plants are present that look (and are) acceptable to both sheep and rabbits, but both herbivores are now eliminated. Under the fixed Pointing Finger, the soil is dark because it has been covered by a biological soil crust that is visible from space – see later. The green woody shrub has grown and joined by others on the RHS:

65 years on: Bluebush shrubs continue to dominate the landscape because they have grown in size, particularly the pair closest to the Pointing Finger. The Saltbush shrubs, right hand side foreground, have become decrepit and senescent. The biological soil crust is now quite distinct compared with the small patch of bare soil under the Pointing Finger. The tall green woody shrubs grow in size and number:

74 years on: Two immediate impressions. The first is the appearance green sub-shrubs generated by an above average rainfall. The second is that the two LHS Bluebushes, visible since 1944, now appear senescent 66 years later, as does the sea of Bluebushes in the background. The senescing Saltbush shrubs, right hand side foreground earlier, have disappeared:

81 years on: An average rainfall year provides for a foreground almost devoid of annual plants but with a complete coverage of biological soil crust. The 70+ year old Bluebushes on the left hand side are now senescing, as is a tall woody tree, LHS background, that first appeared in 1991. The landscape appears quiet, even tired. But these are not scientific descriptions:

The starkest possible contrast. To the question ‘will this landscape recover?’, the answer is ‘Yes, with zero grazing, it will recover slowly, with rainfall-determined bursts’.

To finish: A satellite image of the Koonamore experimental site. The entire area (400 hectares/990 acres) is a very deep brown because of the biological soil crust that developed since all sheep were removed in 1925. Interesting!