Bob Woolley of Asheville, NC, sent photos he took of a biological marvel: a ray in a nearby aquarium that’s pregnant although it didn’t mate! He sent the paragraph below:

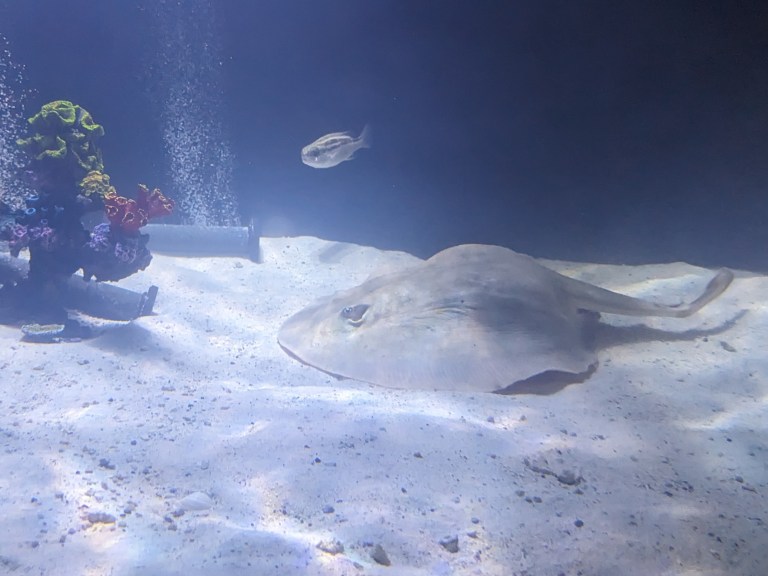

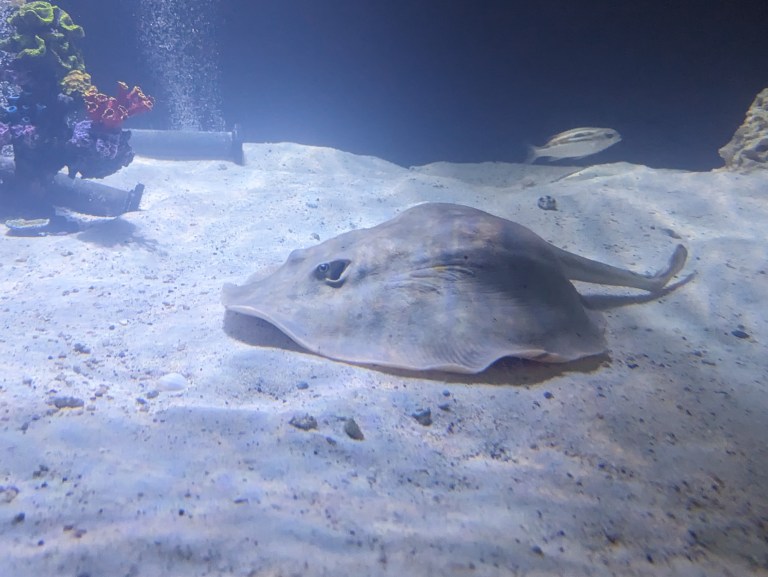

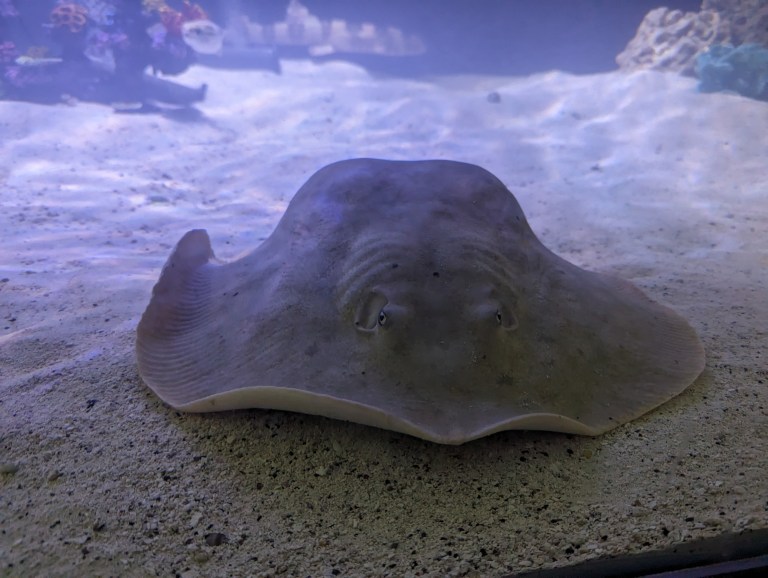

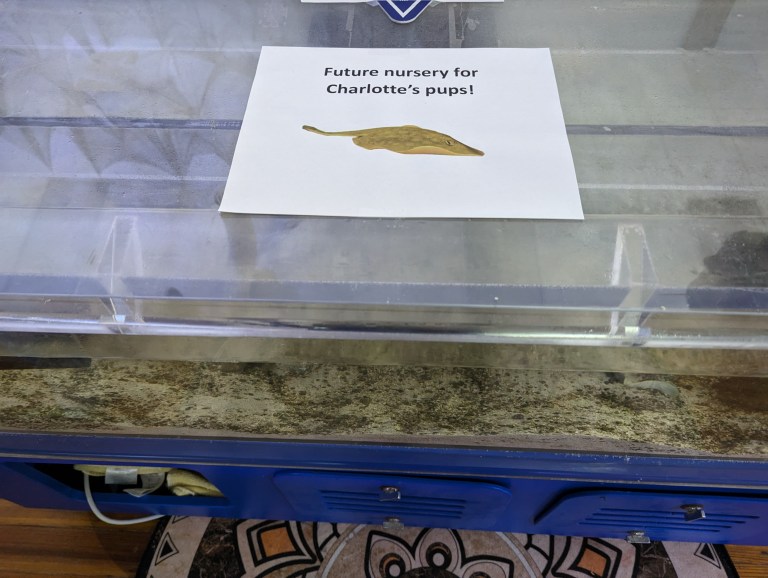

“Charlotte” is a round ray in an aquarium in Hendersonville, NC, who was recently found to be pregnant by parthenogenesis—the first documented case for her species. See this site. Hendersonville is the next city south of Asheville, where I live, so yesterday I drove down there to see her. They seem to be taking very good care of her, with a clean, well-aerated tank–and they’re even preparing a special tank for her babies when they’re born. I thought you might like to feature some photos of this very special girl. You can easily see her “baby bump”; she’s not nearly as flat as most of her kind. In fact, that’s what prompted her human staff to do an ultrasound to see what was going on.

The Associated Press also has the story:

Charlotte, a rust-colored stingray the size of a serving platter, has spent much of her life gliding around the confines of a storefront aquarium in North Carolina’s Appalachian Mountains.

She’s 2,300 miles (3,700 kilometers) from her natural habitat under the waves off southern California. And she hasn’t shared a tank of water with a male of her species in at least eight years.

And yet nature has found a way, the aquarium’s owner said: The stingray is pregnant with as many as four pups and could give birth in the next two weeks.

“Here’s our girl saying, ’Hey, Happy Valentine’s Day! Let’s have some pups!” said Brenda Ramer, executive director of the Aquarium and Shark Lab on Main Street in downtown Hendersonville.

An expert on the stingrays said it would have been impossible for Charlotte to have mated with one of the five small sharks that share her tank, despite news reports suggesting that was the case after Ramer joked about a possible interspecies hookup.

. . . .Its biggest lesson now is on the process of parthenogenesis: a type of asexual reproduction in which offspring develop from unfertilized eggs, meaning there is no genetic contribution by a male.

The mostly rare phenomenon can occur in some insects, fish, amphibians, birds and reptiles, but not mammals. Documented examples have included California condors, Komodo dragons and yellow-bellied water snakes.

Kady Lyons, a research scientist at the Georgia Aquarium in Atlanta who is not involved with the North Carolina aquarium, said Charlotte’s pregnancy is the only documented example she’s aware of for this species, round stingrays.

The pregnancy (yes, it’s developing babies in there, not just eggs), probably resulted from fusion of two of the four cells produced by meiosis, or gamete production. Usually only one of the four cells becomes an egg, which then fuses with a male’s sperm to produce the zygote. But if one of the four cells fuses with another, it’s possible to get an embryo that’s diploid, having the normal two sets of chromosomes,. all from mom. Since different chromosomes assort into the four cells during meiosis, the offspring will not be clones of the mother, or of each other. And this phenomenon has been seen in other sharks, skates and rays, but not this species.

I think they should name the offspring variants of “Jesus” or “Christ” since they were produced without copulation.

Go here to read more about the round stingray (Urobatis halleri), which is in the class Chondrichthyes (cartilaginous fish) along with the sharks, skates, and other rays. Now here are Bob’s photos:

Note that Charlotte isn’t flat (they’re about the size of a dinner plate), but has a big lump towards her rear: the sign of a pregnancy.