UPDATE: I forgot one argument of which readers reminded me: the “slippery slope argument.” To wit:

5. Assisted suicide laws could lead to a “slippery slope” condition whereby shady doctors allow people to be medically euthanized for curable conditions, or even to allow relatives to kill their grandmothers. Yes, this is a danger, though one that can be ameliorated with sufficient stringent vetting laws. The “kill your grandmother” argument can be prevented completely, and certifying certain doctors and shrinks for their objectivity in vetting would be another good step. But when weighed against the suffering eliminated by assisted dying laws, I think the slippery-slope argument, while surely worth considering, is outweighed.

________________________

Assisted suicide for people who have severe and incurable mental illness has always seemed a no-brainer to me, but I’m surprised at the number of people who push back when I bring this up. But, if the procedure is implemented properly, the objections to it don’t seem tenable, and in the end seem to resemble arguments against abortion. That is, the pusher-backers say that people in tough spots shouldn’t have control over their bodies, that the procedure might spread if it’s allowed, and, underneath the objections of many, we find religious feelings—in this case feelings like “God will take you when He’s ready, not when you’re ready.”

Yet it seems to me undeniable that some cases of mental illness, like the main one documented in the Free Press article below, are so severe that they resemble terminal illnesses—illnesses for which enlightened people would favor assisted suicide (I might use the term “euthanasia”) in this post. If you’re terminally depressed, in horrible mental pain all the time, constantly thinking about suicide, and have tried every possible remedy without any success, then why aren’t you in a position similar to that of a cancer patient who, having tried all remedies, now faces a finite term of horrible pain ending certain death? (I presume you’re aware that even in states not permitting assisted suicide, doctors often mercifully end the lives of such patients by giving them an overdose of morphine.)

The difference with mental illness is that death is not certain and the pain will last a lifetime. Sure, maybe researchers will come up with a cure for an intractable mental illness, but that also holds for terminal physical illnesses. People with bad prognoses often hope that a cure will be discovered before they die.

Now for the state to effect euthanasia, there must of course be restrictions. Beyond that, anybody has, in my view, the right to kill themselves by other means, like hanging, shooting, or jumping in front of a train. That kind of suicide is illegal, though I think the illegality is nuts. But for the government to help you die, it’s not proper to provide anybody with the means of euthanasia. There are many reasons, but I won’t enumerate them.

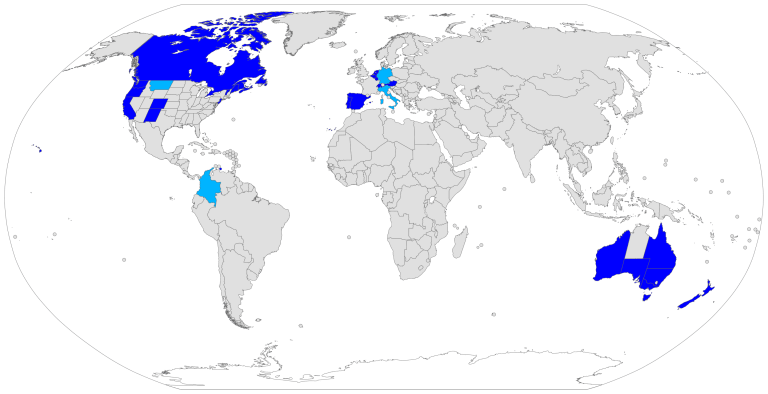

Naturally, in places where euthanasia is officially legal (see the map below), there are such restrictions for the physically ill:

Physician-assisted suicide is legal in some countries, under certain circumstances, including Austria, Belgium, Canada, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, parts of the United States and all six states of Australia. The constitutional courts of Colombia, Germany and Italy legalized assisted suicide, but their governments have not legislated or regulated the practice yet.

In most of those states or countries, to qualify for legal assistance, individuals who seek a physician-assisted suicide must meet certain criteria, including: they are of sound mind, voluntarily and repeatedly expressing their wish to die, and taking the specified, lethal dose by their own hand. The laws vary in scope from place to place. In the United States, PAS [physician-assisted suicide] is limited to those who have a prognosis of six months or less to live. In other countries such as Germany, Canada, Switzerland, Spain, Italy, Austria, Belgium and the Netherlands, a terminal diagnosis is not a requirement and voluntary euthanasia is additionally allowed.

Below is a map of where assisted suicide is legal throughout the world, and there aren’t many places. The states in the U.S. where it’s legal include Maine, Hawaii, Washington D.C., Washington State, Colorado, New Mexico, New Jersey, Vermont, and Oregon. But in no state is assisted suicide permitted for those with mental illness. For physical illnesses or other conditions that are likely to kill you in a few months, here are the general criteria in the U.S.:

- an adult as defined by the state

- a resident of the state where the law is in effect

- capable of using the prescribed medications without assistance

- able to make your own healthcare decisions and communicate them

- living with a terminal illness that is expected to cause death within 6 months as verified by qualified healthcare professionals

Places where assisted dying is legal (see the key for variations):

Places that permit euthanasia for those with mental illnesses include only the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, and—perhaps after 2027—Canada. I haven’t looked up the criteria for state assistance for euthanasia for the mentally ill in all four countries, but here are the criteria for the Netherlands given in the Free Press article below by writer Rupa Subramanya.

Dutch law requires those seeking assisted suicide to show they are in great pain, have no alternative, and are acting of their own volition. They also must get sign-off from at least two doctors, including a psychiatrist. The process can take a few years, culminating with a doctor giving the patient a fatal medication or, if done by oneself, a cup filled with poison to drink. When it’s over, a government panel reviews the case to ensure everything was above board.

Click below to read the article. The woman pictured, Zoraya ter Beek, suffered her whole short life from depression, autism, and borderline personality disorder, and said she was in constant pain. Nothing helped, and eventually the doctors and shrinks said there was nothing more that they could do for her. Tired of living, she applied for and qualified for assisted suicide. She is still alive but scheduled to die in May. (That isn’t final, of course, for I’ve read of such patients who change their minds at the last minute, willing to go on but heartened by the fact that at any time they could choose to die.) Her boyfriend loves her, but agrees with her decision.

Here are some of the objections to assisted suicide for mental illness, and my responses (all text is mine).

1.) The patient could get better but, by taking their life, are depriving themselves of a livable and perhaps enjoyable future. Yes, but that’s true of even physical illnesses. Besides, the prognosis must be confirmed by several doctors and examined post facto by the state. And I would ask those who make this argument, “Who are you to tell someone that they must go on living when they’re in intractable pain?” For those of us who have been severely depressed, it’s hard to convey to others that this kind of severe and prolonged mental pain is fully capable of making you wish to die.

2.) It’s up to God to determine when you die, not you. As an atheist, or even as a rationalist, I find this argument bogus. Here it’s similar to the religious argument against abortion, assisted suicide for physical illnesses, or, as Peter Singer discusses, euthanasia for newborn babies who have a condition that will cause them to suffer and, ultimately, kill them with certainty in a short time. Besides, are you going to base medical decisions on assuming that there’s a god for which we have no good empirical evidence? Isn’t medical treatment supposed to be based on empirical criteria? Do you tell a dying atheist that you can’t increase the morphine drip because God doesn’t want that?

Here’s a quote from the article:

All this pointed to a “dystopian view of the future,” said Theo Boer, the healthcare ethics professor.

“Whether or not you’re religious, killing yourself, taking your own life, saying that I’m done with life before life is done with me, I think that reflects a poverty of spirit,” Boer told me.

. . . . Theo Boer, the bioethicist, acknowledged that none of the suicides in the Bible is condemned, but he added that they are not lionized or commemorated either.

“Suicide in the Bible belongs in the realm of the tragic, and the tragic should not be condemned—nor should it be regulated or celebrated,” he said.

This palaver, including the phrases “Life is done with me” and “poverty of spirit” seems to reflect religious belief, but it’s already clear from opposition to euthanasia in many places (especially the U.S.) that we shouldn’t cut short what is up to God to determine. But if God is omnipotent, wouldn’t He be behind a mentally ill person’s decision to have assisted euthanasia?

3.) It’s contagious. There are several statistics given in the article about assisted dying increasing over time. Most are for physical conditions, with only one for mental illness (my bolding)

In 2001, the Netherlands became the first country in the world to make euthanasia legal. Since then, the number of people who increasingly choose to die is startling.

In 2022, the most recent year for which there is data, Dutch officials recorded 8,720 cases of euthanasia, a 13.7 percent increase from 2021, when there were 7,666 cases. To put this in perspective, there were a total of 170,100 deaths in the Netherlands in 2022—meaning euthanasia cases comprised more than 5 percent.

“This upward trend, in both the absolute and relative numbers, has been visible for a number of years,” the country’s Regional Euthanasia Review Committee’s 2022 Annual Report states. What’s more, the number of euthanized people between the ages of 18 and 40 jumped from 77 in 2021 to 86 in 2022. And the number of people with psychiatric disorders who choose euthanasia is rising: In 2011, there were just 13 cases; in 2013, there were 42; and by 2021, there were 115.

This trend is not limited to the Netherlands. From 2018 to 2021, countries where euthanasia or assisted suicide is most popular saw sizable increases in the number of people signing up to die: In the United States, where ten states and the District of Columbia have physician-assisted suicide, there was a 53 percent jump; in Canada, 125 percent.

But why wouldn’t you expect the numbers to rise as people become aware that they have this alternative? It’s not written about very often, so you have to see articles like this to find out about it. But even so, this is a question of ethics, not of statistics. If the regulations are sufficiently rational and stringent that they prohibit spur-of-the-moment suicides or mental conditions for which every possible cure hasn’t been tried, why should we care about the increase? And wouldn’t you want the ability to die a peaceful and painless death if you had a condition that could be terminated in a peaceful way, at a time and place of your choosing, and when you are surrounded by loved ones? (This is, as I’ve learned, the way it usually occurs.)

4.) It hurts those who are left behind. I’ve heard this argument used often against those who discuss self-inflicted suicide. “If you kill yourself, think of all the people who will miss you and be in pain.” But this seems eminently selfish to me. Everybody who dies before their friends, relatives, and loved ones (and that means all of us) faces that as a certainty. If someone’s in intractable physical pain and dying of cancer, would you tell them to hang on for your sake? Of course not! The same holds for incurable mental illnesses. It’s selfish and boorish to ask someone to stay alive for the sake of your—or other people’s—feelings.

For #5, see the update at top.

For some people, suicide is simply a no-go zone, which is why suicide hotlines exist to talk those who wish to die out of that wish. But that’s different, for someone who calls a hotline has a good chance that they’re simply emitting a cry for help, and want to be talked out of it. (However, some do kill themselves.) That’s why I think those hotlines are great things. But assisted dying with stringent criteria needed to qualify, and the use of drugs that assure a painless death, are not equivalent to a suicide hotline.

I’m sure that ethical philosophers have discussed this issue before, and feel free to cite articles below if you know of them (I don’t). These are of course tentative ideas that I’ve thought about for a long time (note: I’m NOT a candidate!), and were given shape by the article above, but I’m willing to listen to other points of view. If you have them, or if you agree with what I’ve said, weigh in below. But do read the Free Press piece.