There are many things to criticize about this new paper in Science (one of three “woke” papers in the issue), but to me the worst is its denial of the sex binary. For that binary, whose existence the authors even admit, is considered by them to exemplify “essentialism”—the object of the paper’s attack. By including more about variation in traits, including the sex of individuals, say the authors, there can be “a broad decrease in gender essentialist beliefs among US adolescents.” And they demonstrate this push for essentialism and neglect of trait variation by surveying genetics chapters of six high-school biology texts.

This, in other words, is an ideologically motivated paper, and it shows. And the object of its publication is a familiar one: to buttress people who see themselves as “variant” in terms of gender “nonbinary”. But of course the “essentialist” sex binary is simply a fact of nature, and should not lead to demonization of those who feel they’re of their non-natal sex. Nature gives us no lessons about how to treat people outside the “norm.” Yes, binary people don’t feel that they’re either male or female, and that’s okay and should be respected, but you can’t say that the biological sexes in plants and animals form a spectrum. Yet that’s just what the authors say.

Now there may be something worthwhile in this paper insofar as it points out how textbooks have neglectedf genetic and environmental variation that causes differences between groups. But whether one has to go into a long disquisition on variation in high school biology is debatable (see below for one of the confusing changes they suggest). Further, the examples of “essentialism” they show aren’t very convincing. Finally, most of the paper is simply confusing as well as tendentious.

Click on the title below to see the short paper (four pages, the pdf is here):

I read the paper three times, and my marking-up of my copy below shows how many comments I had. I won’t bore you with most of them, though!

The authors go after what they see as three misguided views promulgated in the textbooks they surveyed:

Three basic assumptions undergird the essentialist view of sex and gender (1): (i) there is little to no variation in traits or behaviors within a sex or gender group; (ii) differences between sexes or genders are discrete—the groups do not overlap substantially in traits; and (iii) internal factors such as genes are the best explanation for all forms of variation within and between sex or gender groups. Scientific research on sex and gender is inconsistent with these assumptions (3, 4), yet they are commonly held. For example, substantial portions of US adults (≈40 to 70%) attribute gender differences in traits and behaviors to genetic causes (5).

References 3 and 4 recur throughout the paper as “evidence”. I’ve glanced at one of them, and didn’t see it saying what the authors claimed, but readers should check for themselves. At any rate, certainly biologists recognize that these tropes are wrong. There is ample variation among individuals within a sex or gender group (the authors conflate sex and gender, and eventually combine them as “sex/gender”, which is a mistake); for nearly all traits there is substantial variation among individuals of a sex (I’ll leave gender aside for now); and, finally, saying that “internal factors such as genes are touted as “the best explanation for all forms of variation within sex or gender groups” is, to a biologist, nonsensical. We don’t use terms like “best explanation”. If we want to look at variation within a group, we can measure the proportion of variation among individuals by a figure called the heritability, which runs from 0 (no variation in traits due to variation among individuals in their genes [religion is a likely example] to 1 (all variation among individuals is due to variation in their genes). To say genetic or environmental variation is a “best” explanation is ridiculous because it depends on the trait, the environment, and the population.

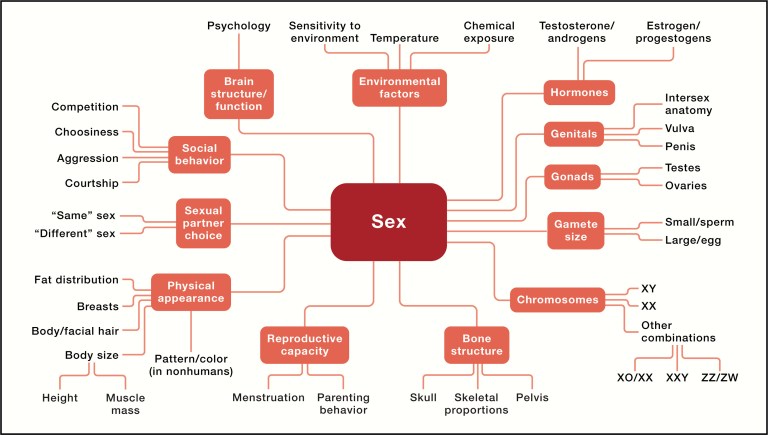

What is the definition of sex? The authors first more or less admit that it’s indeed a binary based on gametes, but then say how “complex” it is, which of course sex determination, particularly with respect to secondary sexual traits is. The first conflation is how many sexes there are, which has a simple answer, with how sex produces an individuals’s appearance and other traits, which has a complicated answer. They then conflate sex with gender, using the term “sex/gender”. Bolding in the excerpt below is mine, and note how they confuse the definition of sex with the determination of sex through development. The former is a simple binary, while the latter is indeed complex.

Sexual reproduction generates new allelic combinations within a species (3). Sex determination is the process by which an organism develops a particular sex—the ability to produce a particular type of gamete, along with any associated phenotypic traits. This process is tremendously variable across species. In some species (such as cichlid fish), an individual’s sex can be determined by the temperature of their physical surroundings and can reverse. Some species have more than two sexes (for example, some fungi have thousands); others have more than two sex chromosomes (for example, the platypus has 10) or sex chromosomes other than X and Y (for example, birds have Z and W sex chromosomes).

But just because how gametes are produced within a species, or sex-associated traits are determined, are complex, doesn’t mean that sex isn’t a binary. It’s also a binary in animals where sex determination is produced by temperature (turtles), haploidy vs. diploidy (bees), or social environment (some fish). They tack on “associated phenotypic traits” as part of the sex definition, which is wrong.

The conflation of the sex binary with the variation in sex-associated traits leads them to somehow implicitly dismiss the binary:

As a result of this complexity, human sex variation is not strictly dichotomous at the biological level; rather, it is best described as a somewhat continuous, bimodal distribution (3). This biological variation intersects with the cultural practices of medical clinicians to influence sex assignment (3), often in ways that reduce the underlying biological complexity to a simpler binary: females and males. However, many intersex humans exist who blur the hard lines between males and females (3).

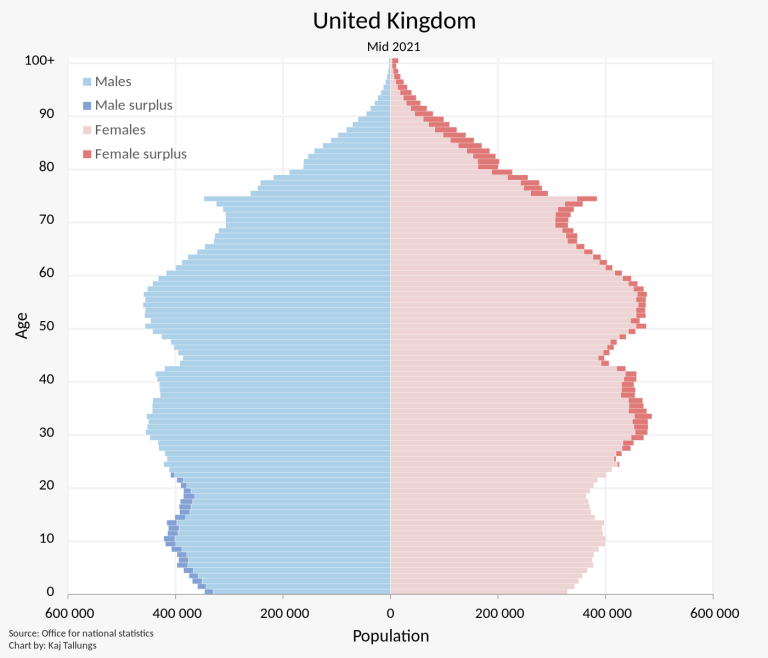

The proportion of individuals who are either male or female, based having the developmental equipment for making big or small gametes, is not “somewhat continuous”. It is nearly completely binary, with only 0.018% of individuals (as the authors admit, about 1 in 5600—they say 2 in 10,000—being of indeterminate sex, including intersexes). That means that 99.982% of individuals lie in the two peaks, or rather two straight lines shooting upwards. This is not at all “somewhat continuous” it is all but binary with a teeny blip in the center. Call that “very very very very strongly bimodal” if you wish, but the proportion of indeterminate individuals is miniscule, and these individuals are not a third sex, but represent developmental anomalies. Essentialism is in effect the case here: there are only two sexes and a very few individuals of indeterminate sex.

Another mistake they make is to claim that although gender (what sex role you think you enact) is socially constructed, that means that gender has nothing to do with biology:

Altogether, nearly all trait variation that exists within and between human sexes is not what essentialism predicts, and neither is the causal source of this variation (that is, there are no genetic “essences”).

The same arguments apply to gender, perhaps even more forcefully, because gender is a socially constructed lay interpretation of the biological phenomenon of sex (3, 4). Individuals who identify as women or girls are often expected to adopt a set of socially and culturally prescribed activities, abilities, and interests that distinguish them from individuals who identify as men or boys (3, 4). Thus, differences in complex traits (such as activities, abilities, and interests) between individuals who identify as different genders have no biological basis and are instead explained by sociocultural factors (4).

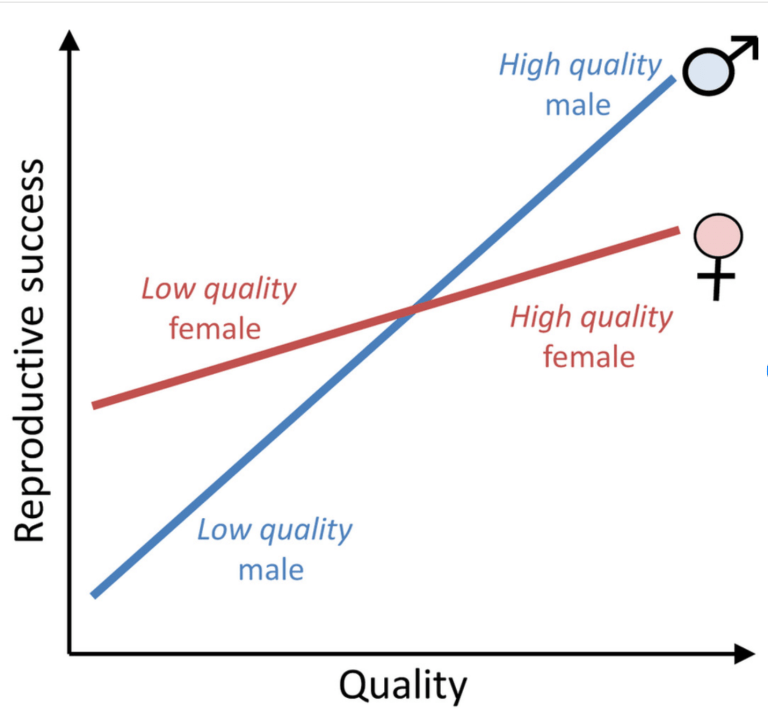

But the vast majority of individuals have a “gender” that corresponds with their biological sex, with individuals showing typical sex-associated traits such as differences in aggression, risk-taking, interest in people vs. things, and so on. As Luana and I showed in our Skeptical Inquirer paper, many of these traits have an evolved genetic/biological basis. If that’s the case, then a hefty proportion of “gender roles” also have a biological component (see #2 in our paper). To say that there is no biology in gender roles is simply ludicrous.

On to the textbooks.

Variation within sex/gender groups. Using rather fuzzy and subjective criteria, the authors argue that sex and gender are presented in textbooks as essentialist, even though the sexes themselves, as a binary, are essentialist. Gender is of course variable, but they don’t show examples of “essentialism” in gender in this paper. Here’s their analysis:

Twelve percent of paragraphs described individuals of a single sex/gender group as uniform [β = 0.12, 95% CI (0.08, 0.17)] (see SM for analytic strategy). In addition, 10% of paragraphs described individuals of a single sex/gender group as differing by type [β = 0.10, 95% CI (0.05, 0.16)]. By contrast, descriptions of continuous variation within a sex/gender group occurred in only 3% of paragraphs [β = 0.03, 95% CI (0.01, 0.05)].

Note that “sex” has now become “sex/gender”. If you mix them together, then there’s a danger of textbooks conflating the sex binary with the variability of gender identification, and you wind up with a nonsensical analysis.

Variation between sex/gender groups. Here, coding the textbook paragraphs, the authors found no tendency for textbooks show discrete differences between sex/gender groups (note again how they confuse the results by mixing “sex” and “gender”) as opposed to showing overlaps and variation. In other words, their hypothesis of essentialism was falsified!

Sixteen percent of paragraphs described categorical differences between sex/gender groups [β = 0.16, 95% CI (0.10, 0.22)]. By contrast, only 11% of paragraphs described similarities or overlaps across sex/gender groups [β = 0.11, 95% CI (0.06, 0.16)]. The difference between these code proportions was not statistically significant [β = 0.05, 95% CI (-0.01, 0.11)].

But they decide the difference is significant anyway—because there is overlap between the groups, ergo no essentialism:

Yet because sex/gender groups overlap considerably on most complex traits (3, 4), even this seemingly balanced presentation of similarities and categorical differences is more consistent with essentialism than with the scientific consensus on sex and gender.

They try to save their hypothesis even though the statistics don’t support it.

Internal versus external explanations. What the authors are looking for here are whether textbooks describe variation within and between “sex/gender” groups as having an internal explanation (genetic) or external explanations (presumably environmental and social factors). Here they find mostly internalist explanations—that is, their hypothesis of textbooks being “essentialist” is confirmed:

Internal explanations were given in 12% of paragraphs [β = 0.12, 95% CI (0.06, 0.20)]. External explanations were given in only 1% of paragraphs [β = 0.01, 95% CI (0.003, 0.02)]. This difference was statistically significant [β = 0.11, 95% CI (0.05, 0.19)].

To see how they coded textbook passages as essentialist (or internalist), and how the authors recommend that textbooks be rewritten, here’s their table (click to enlarge):

It’s true that tongue-rolling is no longer seen as a dominant, single-gene allele, so correcting that is okay. Note, though the authors’ admission (yellow) that intersex individuals are rare, so that one really falls more into “discreteness” rather than “continuity”.

The second paragraph from the textbook (lower left) is much better than the authors’ revision (lower right), particularly for recessive traits, because the “suggested” version is simply confusing. They throw in “variation” simply because, as any geneticist knows, the severity of a genetic disease varies among people. Yet they see the revised version as infinitely superior to the textbook version because their revision less uniform and more continuous. I find it overly complicated and confusing.

The lesson the authors draw from looking at single chapters of six high-school biology textbooks, then, is that essentialism is the norm, and that’s bad. But I suspect, given how they treated “variation between sex/gender groups”, and their conflation of sex and gender, that there’s some cherry-picking going on. At any rate, having taught genetics, though not in high school, I think this paper is making a great deal out of relatively little. It is paragraphs like these that make me think the motive is ideological, and thus the textbooks must be altered to conform with the authors’ preferred ideology:

One limitation of our study is that we did not search for sex and gender terms outside of genetics chapters. We may have thus underidentified messages that are inconsistent with essentialism about sex and gender. However, qualitative studies that have analyzed the nongenetics chapters of biology textbooks by using the lenses of feminist and queer theory—which were developed to uncover and counter gender essentialism—do not support this optimistic view (15).

Readers who are interested in this claim can read reference 15 here.

The authors continuously argue that textbooks are “inconsistent with scientific reality”, as if the sex binary were not “scientific reality” (notice that they concentrate on sex and gender, which itself is telling). Their object is clearly to show that everything forms a spectrum, and so any variation in gender (I won’t admit that there’s variation in sex, except for the 0.018% of indeterminate individuals) is fine. And it is fine, but not because biology is always a spectrum.

Here’s another paragraph

When describing sex/gender groups as uniform, or as composed of different types, biology textbooks are expressing essentialist views that are inconsistent with scientific reality: It is continuous variation that is the norm within sex and gender groups. When describing between-group variation, biology textbooks discuss differences and similarities at similar rates. In actuality, sex and gender groups overlap substantially on most complex traits (3, 4). Rather than reflecting this reality, textbooks paint a picture that is consistent with the essentialist notion that sex and gender groups are discrete.

Note that again they get themselves into the weeds by conflating sex (which is discrete) with gender (which isn’t). They themselves promulgate confusion in this paper which, in the end, seems to me to make no progress in achieving social justice. Yes, the authors correct a few biological errors in textbooks, like the genetics of tongue rolling, but it takes a while for high-school texts to catch up to recent research.

I received a link to this paper from several colleagues I respect, all of them more or less outraged by the sloppy methodology, tendentious analysis, and ideological overtones.

I’ll quote one colleague’s view:

This paper on sex and gender in biology textbooks was recommended to me yesterday, and I was baffled by it. First, I was baffled that a paper with such a short and simple statistical analysis would be published in a journal like Science. Second, I was baffled that the paper promotes a blank-slateist view os sex differences which considers differences between men and women to be the product of “social construction” (note how they support their claims about gender by repeatedly citing the same two papers). Finally, I think the alleged examples of “essentialism” that they cite from biology textbooks are no such thing, and in fact I could not detect mistakes in the paragraphs that they showed.

The worst part is that they claim that their misguided views are the “consensus” in biology, while only citing a few papers that support their views. I think this paper is a perfect example of how ideology is perverting science and science education, because it uses gender theory in place of mainstream biology.

But of course colleagues who liked the paper (I know of none) wouldn’t be likely to send me the link and beef about thje paper!

I should add that there’s one more paper in this series of three, but I won’t bother you with it. The title and link are below, click if you can bear reading more of this stuff. The ideological leaning of the triumvirate is clear: