If you’ve listened to National Public Radio (NPR) in the past few years, what you’ve heard is basically a progressive, left-wing radio station, not a station that represents American diveristy of opinions and viewpoints. Several of my friends have canceled their subscriptions, even though they’re Democrats and consider themselves on the Left.

But NPR is also publicly funded to some extent. Although it claims that it gets less than 1% of its funding from the government (i.e., from taxpayers like you and me), The Hill notes that “NPR may receive little direct federal funding, but a good deal of its budget comprises federal funds that flow to it indirectly by federal law.”

Regardless, NPR is suppose to be a radio station that all Americans can listen to with profit, not a megaphone for progressive Leftism. Yet, according to this new article in the Free Press by Uri Berliner, the senior editor of NPR’s business desk (and still with the station!), NPR has not only tilted increasingly leftward, with a changing demographic, but has become more “white” as elitist listeners tune in while blacks (and conservatives) don’t listen much. Further, it has bought into stories that were later found dubious or even debunked, yet has never corrected itself. Right now subscriptions are falling, the local branches are laying off workers, and NPR’s future seems uncertain.

Click to read: I’ll summarize it briefly and give a few quotes. Note at the bottom that NPR has officially responded, and I’m unsure whether Berliner has a future at the institution.

First, the changing demographic of listeners:

For decades, since its founding in 1970, a wide swath of America tuned in to NPR for reliable journalism and gorgeous audio pieces with birds singing in the Amazon. Millions came to us for conversations that exposed us to voices around the country and the world radically different from our own—engaging precisely because they were unguarded and unpredictable. No image generated more pride within NPR than the farmer listening to Morning Edition from his or her tractor at sunrise.

Back in 2011, although NPR’s audience tilted a bit to the left, it still bore a resemblance to America at large. Twenty-six percent of listeners described themselves as conservative, 23 percent as middle of the road, and 37 percent as liberal.

By 2023, the picture was completely different: only 11 percent described themselves as very or somewhat conservative, 21 percent as middle of the road, and 67 percent of listeners said they were very or somewhat liberal. We weren’t just losing conservatives; we were also losing moderates and traditional liberals.

An open-minded spirit no longer exists within NPR, and now, predictably, we don’t have an audience that reflects America.

Berliner then goes into three stories in which NPR took positions that ultimately seemed dubious or even indefensible; but in no case did it ever correct itself (three points below are my take):

1.) NPR glommed onto the idea that Trump colluded with the Russians during the 2016 election. No evidence supporting that came out, and NPR quietly dropped the story without any corrections.

2.) NPR poo-pooed the “Hunter Biden laptop story,” barely covering it at all because it didn’t believe the notion that Hunter Biden would use his dad’s name to advance himself. It turned out that, of course, he did. NPR never corrected itself.

3.) NPR bought big-time into the “wild virus wet-market” theory for the origin of COVID, dismissing the idea that the virus came from a leak in a lab in Wuhan, China. As time progressed, the lab-leak theory became more credible, and now, though we still don’t know for sure, the lab-leak seems more credible than the wet market. NPR, however, utterly rejected the lab-leak theory and hasn’t corrected its earlier insistence.

According to Berliner, after the death of George Floyd the station adopted a form of Critical Race Theory, even accusing itself of complicity in racism. Of course if any station is lily-white, it would be this station with its elitist and progressive listeners carrying NPR tote bags and driving Volvos. But it’s startling how quickly the issue of race came to dominate every aspect of NPR:

And we were told that NPR itself was part of the problem. In confessional language he said the leaders of public media, “starting with me—must be aware of how we ourselves have benefited from white privilege in our careers. We must understand the unconscious bias we bring to our work and interactions. And we must commit ourselves—body and soul—to profound changes in ourselves and our institutions.”

He declared that diversity—on our staff and in our audience—was the overriding mission, the “North Star” of the organization. Phrases like “that’s part of the North Star” became part of meetings and more casual conversation.

Race and identity became paramount in nearly every aspect of the workplace. Journalists were required to ask everyone we interviewed their race, gender, and ethnicity (among other questions), and had to enter it in a centralized tracking system. We were given unconscious bias training sessions. A growing DEI staff offered regular meetings imploring us to “start talking about race.” Monthly dialogues were offered for “women of color” and “men of color.” Nonbinary people of color were included, too.

These initiatives, bolstered by a $1 million grant from the NPR Foundation, came from management, from the top down. Crucially, they were in sync culturally with what was happening at the grassroots—among producers, reporters, and other staffers. Most visible was a burgeoning number of employee resource (or affinity) groups based on identity.

They included MGIPOC (Marginalized Genders and Intersex People of Color mentorship program); Mi Gente (Latinx employees at NPR); NPR Noir (black employees at NPR); Southwest Asians and North Africans at NPR; Ummah (for Muslim-identifying employees); Women, Gender-Expansive, and Transgender People in Technology Throughout Public Media; Khevre (Jewish heritage and culture at NPR); and NPR Pride (LGBTQIA employees at NPR).

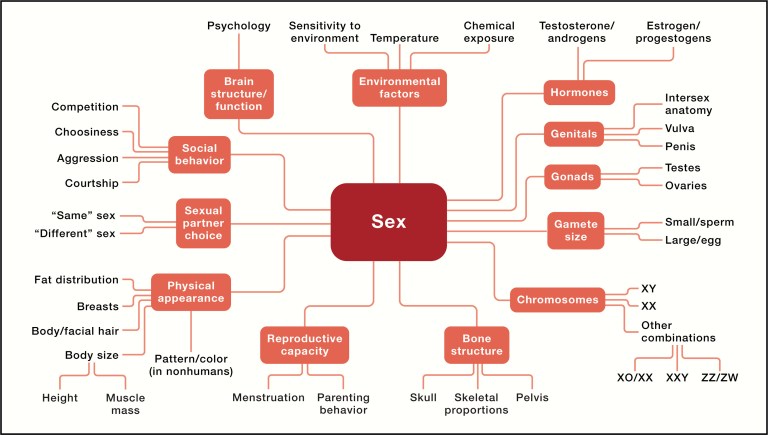

And I read this next bit with utter dismay. Along with the absence of viewpoint diversity in its programs, something that the station simply ignores when it comes up, they’ve bought into gender activism to the point where they can’t use the term “biological sex”! Oy! And of course in the Hamas/Israel war, the station is tilting towards Palestine, because that’s what progressives want to hear: Israel is the white colonialist oppressor. I myself have noticed this even on my short drives around Chicago. Bolding below is mine:

The mindset prevails in choices about language. In a document called NPR Transgender Coverage Guidance—disseminated by news management—we’re asked to avoid the term biological sex. (The editorial guidance was prepared with the help of a former staffer of the National Center for Transgender Equality.) The mindset animates bizarre stories—on how The Beatles and bird names are racially problematic, and others that are alarmingly divisive; justifying looting, with claims that fears about crime are racist; and suggesting that Asian Americans who oppose affirmative action have been manipulated by white conservatives.

More recently, we have approached the Israel-Hamas war and its spillover onto streets and campuses through the “intersectional” lens that has jumped from the faculty lounge to newsrooms. Oppressor versus oppressed. That’s meant highlighting the suffering of Palestinians at almost every turn while downplaying the atrocities of October 7, overlooking how Hamas intentionally puts Palestinian civilians in peril, and giving little weight to the explosion of antisemitic hate around the world.

The inevitable result is that people are tuning out and listening instead to the many podcasts on tap:

These are perilous times for news organizations. Last year, NPR laid off or bought out 10 percent of its staff and canceled four podcasts following a slump in advertising revenue. Our radio audience is dwindling and our podcast downloads are down from 2020. The digital stories on our website rarely have national impact. They aren’t conversation starters. Our competitive advantage in audio—where for years NPR had no peer—is vanishing. There are plenty of informative and entertaining podcasts to choose from.

Berliner offers a solution, which is to return to “traditional” journalism, but in the engaging way it used to. They need to broadcast more diverse viewpoints, perhaps even debates. Since NPR has a new CEO, businesswoman Katherine Maher, only 40, it might change course. I can’t tell enough about her to guess if she’ll change the direction of NPR’s broadcasting.

You may well ask yourself, as I did, “Why on earth does Berliner stay at such a dysfunctional station?” Well, maybe he’s hoping that Maher will effect a big change. But judging from his own narrative, buttressed with emails, names, and evidence, his tenure at NPR now seems to be one big tsuris. And he doesn’t explain why, given this large kvetch, he’s still with the organization.

Sadly, some liberals are dismissing this piece; after all, it’s in the “conservative” Free Press. As one reader wrote me:

A response to it from a friend, a fellow academic:“This guy sounds like a disgruntled MAGA Republican boohoo.”Liberalism is doomed!

*********

Now NPR has pushed back, and it’s not much of a response:

NPR’s chief news executive, Edith Chapin, wrote in a memo to staff Tuesday afternoon that she and the news leadership team strongly reject Berliner’s assessment.

“We’re proud to stand behind the exceptional work that our desks and shows do to cover a wide range of challenging stories,” she wrote. “We believe that inclusion — among our staff, with our sourcing, and in our overall coverage — is critical to telling the nuanced stories of this country and our world.”

She added, “None of our work is above scrutiny or critique. We must have vigorous discussions in the newsroom about how we serve the public as a whole.”

A spokesperson for NPR said Chapin, who also serves as the network’s chief content officer, would have no further comment.

But there are also heated denials from NPR employees rejecting Berliner’s claims. Read the piece to see them. Still, the best way to judge whether NPR is doing what it should do is simply to listen. And, thank Ceiling Cat, you no longer have to listen to the uber-woke and deeply spiritual Krista Tippett, who was let go. As I always said about her, she was so moved by her own profundity that she often came close to tears. Just sayin’.