This is a true test of people like me who are pro-Israel in the current conflict but are also in favor of free speech. But it’s not a hard decision, for if you’re a hard line free-speech advocate, you must accept the fact that it’s most important to allow freedom of speech when what the person says offends you or many others.

And that is the situation in the case of Asna Tabassum, the valedictorian of the University of Southern California (USC), who, apparently because she might talk about (Israeli) genocide or advocate for a Palestine “from the river to the sea”, isn’t going to be allowed to speak at graduation. (Of course, the USC administration uses other excuses for censorship, like “safety”.)

I was alerted to the situation by this tweet sent to me by Luana:

Incredible story. USC offers a minor in “resistance to genocide”, this girl minored in it, was named valedictorian, and then they cancelled her speech because she might talk about genocide https://t.co/Ivk9LFwjAC

— Tom Gara (@tomgara) April 16, 2024

Is this the case? Does USC really have a minor in genocide? Did the valedictorian minor in genocide? And did USC also prevent its valedictorian from speaking because of the possibility she might discuss genocide? The answer to all four questions appears to be “yes”. But I think it’s wrong to prevent her from speaking—not if USC has a tradition of having valedictorians speak, which there is.

First, yes, USC does have a minor in genocide, or rather “resistance to genocide”. Here are part of the details of that minor (click to read), but if you look at the the courses, there’s nothing about Israel/Palestine: most of them are about the Shoah (Holocaust of Jews during WWII), Native American genocide, the Armenian genocide, and genocide and the law. It seems like a creditable minor. Of course one suspects that Tabassum might have minored in this because of a belief that Palestine is undergoing genocide, but we don’t know that, and at any rate it’s irrelevant to this kerfuffle.

This article from the school’s site USC Today (click headline below to read) confirms that Tabassum was indeed the valedictorian:

USC’s 2024 valedictorian, Asna Tabassum, was also recognized. Tabassum, who is graduating with a major in biomedical engineering a minor in resistance to genocide, has studied how technology, immigration and literacy affect the type of medical care people receive. She has also been an advocate for the community through her service with the Muslim Student Union and the Mobile Clinic at USC.

And here are two articles, the first from the Los Angeles Times and the second from USC Annenberg Media, both confirming that Tabassum has indeed been banned buy USC’s administration from speaking. Click both to read, though the quotes below come from the L.A. Times.

And from the USC Annenberg site:

Quotes from the LA Times:

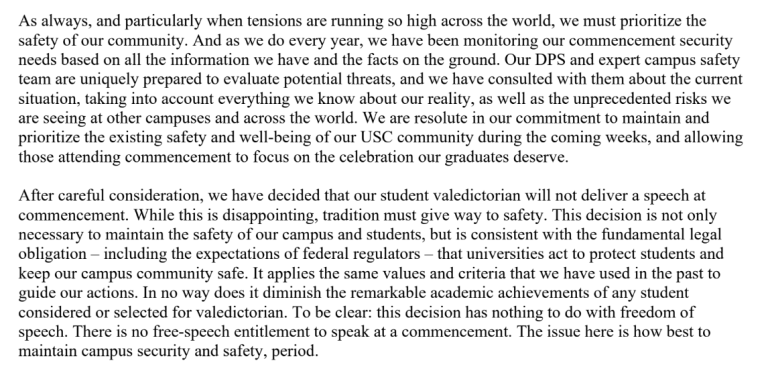

Saying “tradition must give way to safety,” the University of Southern California on Monday made the unprecedented move of barring an undergraduate valedictorian who has come under fire for her pro-Palestinian views from giving a speech at its May graduation ceremony.

The move, according to USC officials, is the first time the university has banned a valedictorian from the traditional chance to speak onstage at the annual commencement ceremony, which typically draws more than 65,000 people to the Los Angeles campus.

In a campuswide letter, USC Provost Andrew T. Guzman cited unnamed threats that have poured in shortly after the university publicized the valedictorian’s name and biography this month. Guzman said attacks against the student for her pro-Palestinian views have reached an “alarming tenor” and “escalated to the point of creating substantial risks relating to security and disruption at commencement.”

. . .“After careful consideration, we have decided that our student valedictorian will not deliver a speech at commencement. … There is no free-speech entitlement to speak at a commencement. The issue here is how best to maintain campus security and safety, period,” Guzman wrote.

The student, whom the letter does not name, is biomedical engineering major Asna Tabassum. USC officials chose Tabassum from nearly 100 student applicants who had GPAs of 3.98 or higher.

But after USC President Carol Folt announced her selection, a swarm of on- and off-campus groups attacked Tabassum. They targeted her minor, resistance to genocide, as well as her pro-Palestinian views and “likes” expressed through her Instagram account.

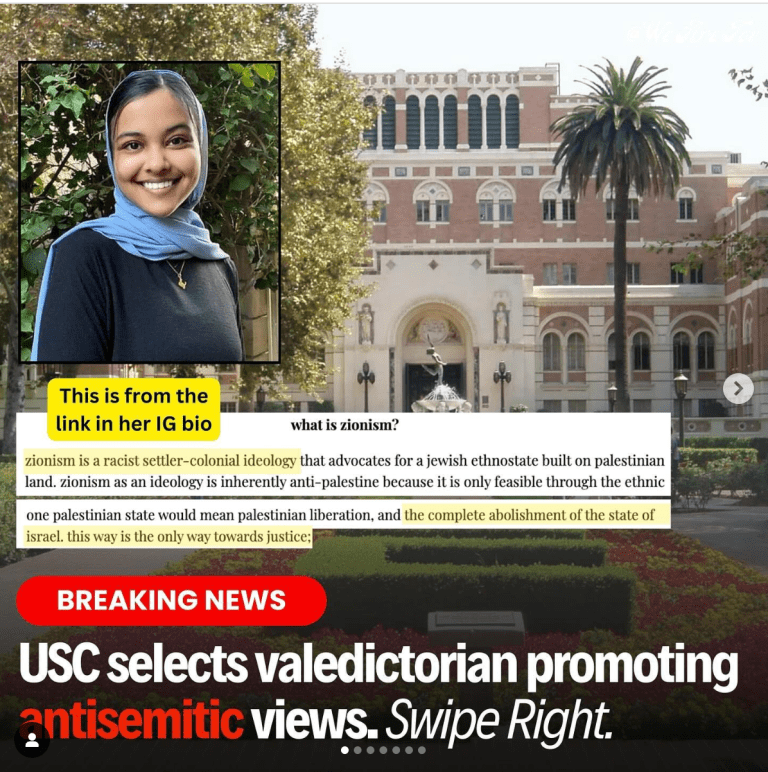

Here’s an Instagram post quoting Tabassum and calling for her deplatforming. Her own Instagram site is now private, but note that the words are probably not hers, but from a link in her own Instagram biography.

And even if the words quoted above were hers, do they promote imminent violence (presumably towards Jews)? Nope. It’s not a First-Amendment exception to call Zionism a “racist settler-colonial ideology, nor to call for the complete abolition of Israel. If it were, half of Twitter would be taken down.

As expected, Tabassum didn’t like this decision, and issued a mature but passionate statement:

In a statement, Tabassum opposed the decision, saying USC has “abandoned” her.

“Although this should have been a time of celebration for my family, friends, professors, and classmates, anti-Muslim and anti-Palestinian voices have subjected me to a campaign of racist hatred because of my uncompromising belief in human rights for all,” said Tabassum, who is Muslim.

“This campaign to prevent me from addressing my peers at commencement has evidently accomplished its goal: today, USC administrators informed me that the university will no longer allow me to speak at commencement due to supposed security concerns,” she wrote.

“I am both shocked by this decision and profoundly disappointed that the university is succumbing to a campaign of hate meant to silence my voice. I am not surprised by those who attempt to propagate hatred. I am surprised that my own university—my home for four years—has abandoned me.”

And of course the university issued a weaselly decision:

In an interview, Guzman said the university has been “in close contact with the student” and would “provide her support.” He added that “we weren’t seeking her opinion” on the ban.

“This is a security decision,” he said. “This is not about the identity of the speaker, it’s not about the things the valedictorian has said in the past. We have to put as our top priority ensuring that the campus and community is safe.”

A screenshot from Provost Andrew Guzman, who singlehandedly decided to ban Tabassum (he doesn’t even have the guts to name her in the letter):

Some of those who objected were, of course, Jewish groups:

We Are Tov, a group that uses the Hebrew word for “good” and describes itself as “dedicated to combating antisemitism,” posted Tabassum’s image on its Instagram account and said she “openly promotes antisemitic writings.” The group also criticized Tabassum for liking Instagram posts from “Trojans for Palestine.” Tabassum’s Instagram bio links to a landing page that says “learn about what’s happening in Palestine, and how to help.”

The campus group Trojans for Israel also posted on its Instagram account, calling for Folt’s “reconsideration” of Tabassum for what it described as her “antisemitic and anti-Zionist rhetoric.” The group said Tabassum’s Instagram bio linked to a page that called Zionism a “racist settler-colonial ideology.”

Well, I have little doubt, based on the above, that Tabassum is pro-Palestinian, may feel that Israel is committing genocide, and has made social-media posts that may smack of antisemitism and perhaps a desire to eliminate Israel. But none of that is relevant here. The only consideration is whether Tabassum’s words are calculated and intended to promote imminent and lawless violence—something that would violate her First-Amendment freedom to speak. And, as a private university, USC doesn’t need to adhere to the First Amendment. They could ban Tabassum without citing freedom of speech. But, like any decent university, public or private, USC should follow the First Amendment. The only exception is that universities should allow “time, place, and manner” expressions of speech that don’t disturb the mission of the university. That means no disrupting speeches or blocking access to university facilities like classes.

Further, USC promotes First-Amendment-like freedom of speech on their website. Here’s one bit from USC’s Policy on Free Speech:

As the Faculty Handbook declares, the University recognizes that students are exposed to thought-provoking ideas as part of their educational experience, and some of these ideas may challenge their beliefs and may lead a student to claim that an educational experience is offensive. Therefore any such issues that arise in the educational context will be considered in keeping with the University’s commitment to academic freedom.

Except, of course, when the issue arises in a graduation speech!

Yes, there may have been threats, but it’s up to USC to have enough security on hand to both protect Ms. Tabassum and also allow her to speak without heckling. The mere citation of threats and palaver about “security decisions” is simply a way that USC can ban a controversial speaker without having to provide the conditions where and when she can speak freely.

Tabassum is a valedictorian, valedictorians traditionally speak at USC, and her speech is almost certainly not designed to incite imminent lawless violence. Even if she accuses Israel of committing genocide in Gaza, that is not sufficient grounds to ban her. (If USC is worried about First-Amendment exceptions, they can vet her speech in advance, but they better have constitutional lawyers look at it, too!).

In my view, USC is cowardly and censorious in preventing Tabassum from speaking at graduation. The school is, as she notes, robbing her of her big moment: her reward for working hard over four years to become the best student in her class. I urge USC to change their minds and let her speak, but of course it’s too late. The gutless wonders, fond of selective censorship, appear to be running USC. And the great irony here is that although the school offers a minor in genocide, it prevents someone from speaking because they might bring up the subject.

_______________

Full disclosure: I was the valedictorian in my college class, too, and was also prevented from the traditional (short) speech because the administration knew I was an antiwar activist. Thus they announced my award from the stage while I was in the audience. I got to stand up when I was recognized, but I was wearing a black armband and made the “Black Power” fist salute. (That cost me a summer job.) I, too, felt a bit cheated, and for reasons similar to those of Tabassum. But I think that the censorship of Tabassum is a much bigger deal than mine given that she was supposed to make a full speech and not just an elongated “thank you”. And, of course, free speech is especially important to emphasize these days. Too many schools are using “safetyism” as a reason to cancel speakers, which merely empowers those who are encouraged to give the “heckler’s veto” and make threats. If a speaker isn’t going to violate the First Amendment, it’s up to the university to protect her and remove those who try to shout her down.

h/t: Luana Maroja