Here are a few misconceptions about college protests being bandied about the internet (in bold) with my responses below them (all text is mine)

a.) If the protests are “peaceful”, then colleges shouldn’t do anything about them

The criterion for colleges to allow free speech, as construed by the courts for state universities, are that speech much be expressed in a “time, place, or manner” in which it doesn’t interfere with the functions or operations of a university (the speech, of course, is not regulated; this rule is ‘content neutral’). Thus state universities can restrict how, when, and where speech can be expressed given the limitations above. Private universities can do the same if “time, place, and manner” regulations are part of their own policy. Note that illegal demonstrations can be peaceful but still prohibited, as when there is loud shouting that disturbs classes or sit-ins that occupy university buildings. Many people who should know better, like AOC or Ilhan Omar, seem to think that peaceful protests on campus must be allowable protests.

AOC instantiates this view below, especially because the protestors were warned but refused to leave. Apparently she wants chaos on the campus. Columbia has already gone to all-hybrid classes, and I suspect that they will cancel graduation, an important time in the life of all students.

Calling in police enforcement on nonviolent demonstrations of young students on campus is an escalatory, reckless, and dangerous act.

It represents a heinous failure of leadership that puts people’s lives at risk. I condemn it in the strongest possible terms.

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) April 24, 2024

This same kind of error is made by many faculty when they sign petitions defending illegal and disruptive demonstrations, like those at Columbia. Here they are prioritizing social justice over the function of their own university. As Jon Haidt would put it, they want to work at Social Justice University, not Truth University.

b.) If the protests are legal under the First Amendment, then colleges must allow them

Again, protests that are legal in public may still be illegal in government institutions like state universities if they interfere with university functions.

c.) Under no circumstances should cops or security people be called to remove protestors

If a disruptive protest is prohibited but protestors refuse to leave, they may and should be gently removed by security or police. Universities don’t like this, but what other way is there to break up an illegal protests that interferes with University function?

d.) Because protestors are practicing “civil disobedience,” they should neither be asked to leave nor be punished with suspensions or arrests

Civil disobedience, as discussed by David French in the article below, means deliberately violating a law that you consider immoral, doing so peacefully, and being willing to accept the punishment. The paradigm for such demonstrations are the civil rights marches and sit-ins of the Sixties. They worked because, by taking their punishment, be it jailing, water hoses, or police dogs, the protestors moved the U.S. morally, showing Americans graphically how segregation was illegal and its proponents immoral. It’s thus almost funny that one of the demands of current protestors, who say they’re engaged in civil disobedience, is that they not be punished for their behavior. Further, what “immoral” law are they violating? Only the “time, place, and manner” restrictions of colleges, though of course they are protesting what they see as Israel’s so-called genocide in Gaza. (And of course they’re protesting their college’s supposed investments in “genocide”.) But they are removed by police not for these things, which constitute free speech, but for illegal and obstructive disruption of a university. The same holds for deplatforming speakers, which is usually not a First-Amendment violation but can be so in government institutions, or for colleges that have a “free speech” policy and take it seriously.

All of these matters are discussed in a new op-ed by NYT writer David French. The NYT original is here, but if you click on the headline below, be able to read it.

French has had a varied career. He grew up in a small town in Kentucky but then went to Harvard Law school and became a lawyer, first a private litigator, then a constitutional lawyer, and finally serving as an Army lawyer. He adds this:

My most recent book, “Divided We Fall: America’s Secession Threat and How to Restore Our Nation,” outlined the dangers of polarization and the need to engage with people who have opposing viewpoints. I’m an evangelical conservative who believes strongly in a classical liberal, pluralistic vision of American democracy, in which people with deep religious, cultural, and moral differences can live and work together and enjoy equal legal protection and shared cultural tolerance. In both my personal and professional life I strive to live up to the high ideals of Micah 6:8 — to act justly, to love kindness, and to walk humbly before God.

We’ll leave aside the God bit as it’s not relevant here. What is relevant is his new piece, which should be sent to every college president, provost, and chancellor in America. If you subscribe you can read it here, but I’ve put an archived version as the link to the headline below, so click on that if you want to read it.

The upshot is that French thinks that universities must observe three principles during this time of protest.

a. Universities must protect free speech

b. Universities must respect peaceful civil disobedience, but

c. Universities must “uphold the rule of law by protecting the campus community from violence and chaos. Universities should not protect students from hurtful ideas, but they must protect their ability to peacefully live and learn in a community of scholars.”

You may notice a bit of conflict between principles b. and c. That means that breaking the rules may be permitted unless it leads to violence and chaos; I interpret “chaos” as the kind of disruption that’s going on at Columbia University. An example of peaceful civil disobedience on campus is the existence of a small encampment of a few tents at Vanderbilt University, the place where Chancellor Diermeier had students expelled and arrested for both sitting in in a campus building and also for injuring a worker as they stormed into the building. Clearly Diermeier (our former Provost) is respecting the right to protest, even though it violates campus regulations, by leaving the small encampment alone.

I’d quote the whole article if I could, but will limit myself to giving French’s take on the issues above. If you’re on a campus, be sure to send this articles to the Powers That Be. French’s quotes are indented. Here’s the gist of French’s “way out” of chaos on campus:

There is profound confusion on campus right now around the distinctions among free speech, civil disobedience and lawlessness. At the same time, some schools also seem confused about their fundamental academic mission. Does the university believe it should be neutral toward campus activism — protecting it as an exercise of the students’ constitutional rights and academic freedoms but not cooperating with student activists to advance shared goals — or does it incorporate activism as part of the educational process itself, including by coordinating with the protesters and encouraging their activism?

The simplest way of outlining the ideal university policy toward protest is to say that it should protect free speech, respect civil disobedience and uphold the rule of law. That means universities should protect the rights of students and faculty members on a viewpoint-neutral basis, and they should endeavor to make sure that every member of the campus community has the same access to campus facilities and resources.

That also means showing no favoritism among competing ideological groups in access to classrooms, in the imposition of campus penalties and in access to educational opportunities. All groups should have equal rights to engage in the full range of protected speech, including by engaging in rhetoric that’s hateful to express and painful to hear. Public chants like “Globalize the intifada” may be repugnant to many ears, but they’re clearly protected by the First Amendment at public universities and by policies protecting free speech and academic freedom at most private universities.

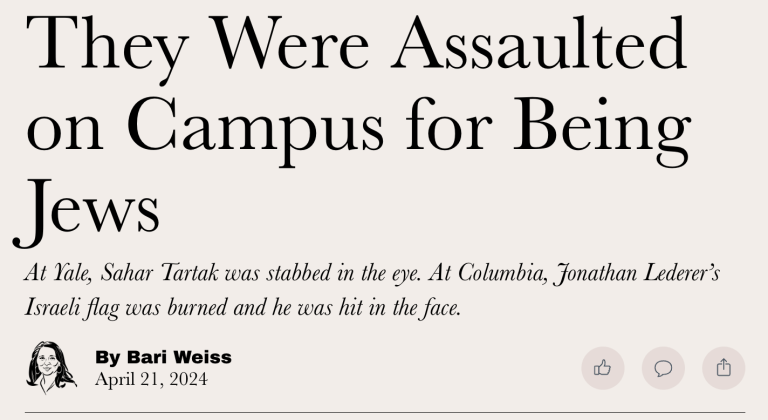

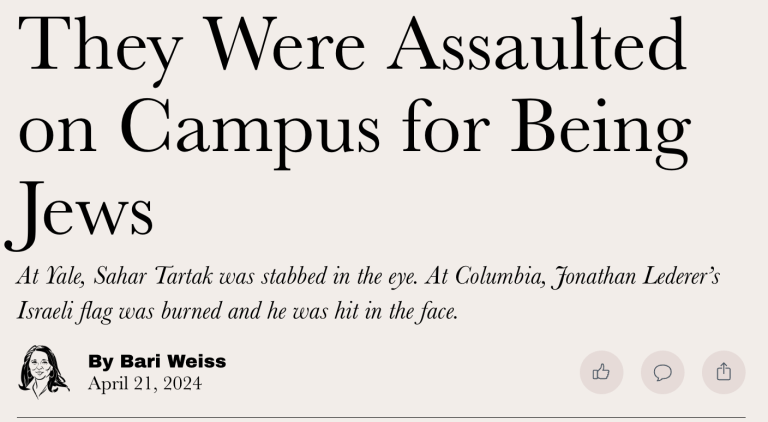

Note that repugnant chants must be tolerated, even if they’re anti-Semitic. I, for one, would not want to punish students for shouting “Gas the Jews,” something that the Columbia protestors come close to. That’s offensive but allowed by the First Amendment. Of course, if the repetition of such sentiments by many create a climate of harassment on campus, that’s a different matter, and a Title VI violation.

It’s a pity that the American public, and especially Representative Stefanik, doesn’t realize that calls for genocide can indeed constitute legal speech. The Presidents of MIT, Harvard, and Penn were accurate in saying that such calls were legal “if expressed in context,” but none of those schools have explicit First Amendment-based speech codes, and the three schools had been irregular and hypocritical in violating what speech codes they do have. This is why it’s essential for all schools to adopt the Chicago Principles of Free Expression—and over 100 of them have done so. (Remember, we’re a private university, too.)

French on time, place, and manner restrictions:

Still, reasonable time, place and manner restrictions are indispensable in this context. Time, place and manner restrictions are content-neutral legal rules that enable a diverse community to share the same space and enjoy equal rights.”

Noise limits can protect the ability of students to study and sleep. Restricting the amount of time any one group can demonstrate on the limited open spaces on campus permits other groups to use the same space. If one group is permitted to occupy a quad indefinitely, for example, then that action by necessity excludes other organizations from the same ground. In that sense, indefinitely occupying a university quad isn’t simply a form of expression; it also functions as a form of exclusion. Put most simply, student groups should be able to take turns using public spaces, for an equal amount of time and during a roughly similar portion of the day.

. . . But what we’re seeing on a number of campuses isn’t free expression, nor is it civil disobedience. It’s outright lawlessness. No matter the frustration of campus activists or their desire to be heard, true civil disobedience shouldn’t violate the rights of others. Indefinitely occupying a quad violates the rights of other speakers to use the same space. Relentless, loud protest violates the rights of students to sleep or study in peace. And when protests become truly threatening or intimidating, they can violate the civil rights of other students, especially if those students are targeted on the basis of their race, sex, color or national origin.

French on the meaning of civil disobedience (his bolding below)

Civil disobedience is distinct from First Amendment-protected speech. It involves both breaking an unjust law and accepting the consequences. There is a long and honorable history of civil disobedience in the United States, but true civil disobedience ultimately honors and respects the rule of law. In a 1965 appearance on “Meet the Press,” the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. described the principle perfectly: “When one breaks the law that conscience tells him is unjust, he must do it openly, he must do it cheerfully, he must do it lovingly, he must do it civilly — not uncivilly — and he must do it with a willingness to accept the penalty.”

. . . . There is a better way. When universities can actually recognize and enforce the distinctions among free speech, civil disobedience and lawlessness, they can protect both the right of students to protest and the rights of students to study and learn in peace.

In March a small band of pro-Palestinian students at Vanderbilt University in Nashville pushed past a security guard so aggressively that they injured him, walked into a university facility that was closed to protest and briefly occupied the building. The university had provided ample space for protest, and both pro-Israel and pro-Palestinian students had been speaking and protesting peacefully on campus since Oct. 7.

But these students weren’t engaged in free speech. Nor were they engaged in true civil disobedience. Civil disobedience does not include assault, and within hours the university shut them down. Three students were arrested in the assault on the security guard, and one was arrested on charges of vandalism. More than 20 students were subjected to university discipline, three were expelled, and one was suspended.

The students demanding amnesty are not practicing true civil disobedience. They want to express their principles but aren’t willing to take the penalty for expressing them in an illegal way. It doesn’t help them, either, that their claim of immorality—that Israel is practicing genocide—is not only wrong, but really does apply to the very entities they worship: terrorist groups like Hamas and Hezbollah. This blatant hypocrisy is called out all too rarely.

French on the importance of viewpoint neutrality:

The message was clear: Every student can protest, but protest has to be peaceful and lawful. In taking this action, Vanderbilt was empowered by its posture of institutional neutrality. It does not take sides in matters of public dispute. Its fundamental role is to maintain a forum for speech, not to set the terms of the debate and certainly not to permit one side to break reasonable rules that protect education and safety on campus.

Vanderbilt is not alone in its commitment to neutrality. The University of Chicago has long adhered to the Kalven principles, a statement of university neutrality articulated in 1967 by a committee led by one of the most respected legal scholars of the last century, Harry Kalven Jr. At their heart, the Kalven principles articulate the view that “the instrument of dissent and criticism is the individual faculty member or the individual student. The university is the home and sponsor of critics; it is not itself the critic. It is, to go back once again to the classic phrase, a community of scholars.”

Contrast Vanderbilt’s precise response with the opposing extremes. In response to the chaos at Columbia, the school is finishing the semester with hybrid classes, pushing thousands of students online. The University of Southern California canceled its main stage commencement ceremony, claiming that the need for additional safety measures made the ceremony impractical. At both schools the inability to guarantee safety and order has diminished the educational experience of their students.

Only about four universities beside Chicago has adopted viewpoint neutrality (Vanderbilt and UNC Chapel Hill are among them), but this principle is just as important as our Principles of Free Expression in keeping open discourse alive at Chicago. Every university should adopt Kalven as well as our principles of free expression. Colleges where I have friends who tell me that their institution refuses to adopt institutional neutrality include Williams College and Appalachian State University. There are many more: for some reason, colleges wish to retain the ability to take political, ideological, and moral stands. Believe me, there is no upside in doing so, for it sets a very bad precedent as well as chilling speech.

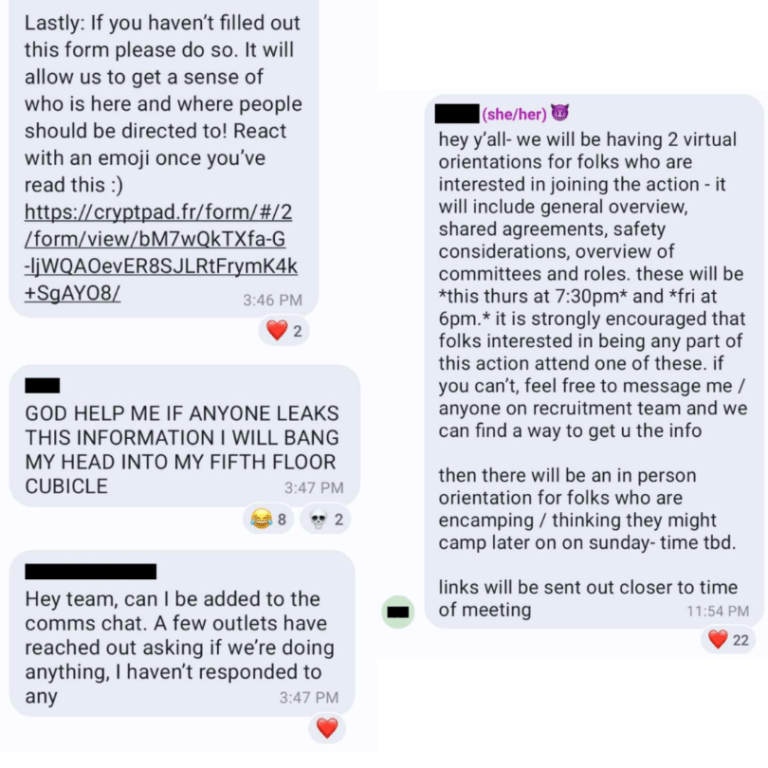

Our own encampment by Students for Justice in Palestine is, says the grapevine, set for Wednesday. The plans apparently call not just for setting up tents, but also occupying buildings—acts that violate campus regulations. I hope to Ceiling Cat that our administration finally grows a spine and enforces those regulations, especially because they have arrantly refused to enforce illegal demonstrations in the past. Right now, our administration appears to be adhering to what French says is a losing strategy:

At this moment, one has the impression that university presidents at several universities are simply hanging on, hoping against hope that they can manage the crisis well enough to survive the school year and close the dorms and praying that passions cool over the summer.

That is a vain hope. There is no indication that the war in Gaza — or certainly the region — will be over by the fall. It’s quite possible that Israel will be engaged in full-scale war on its northern border against Hezbollah. And the United States will be in the midst of a presidential election that could be every bit as contentious as the 2020 contest.

But the summer does give space for a reboot. It allows universities to declare unequivocally that they will protect free speech, respect peaceful civil disobedience and uphold the rule of law by protecting the campus community from violence and chaos. Universities should not protect students from hurtful ideas, but they must protect their ability to peacefully live and learn in a community of scholars. There is no other viable alternative.

**************

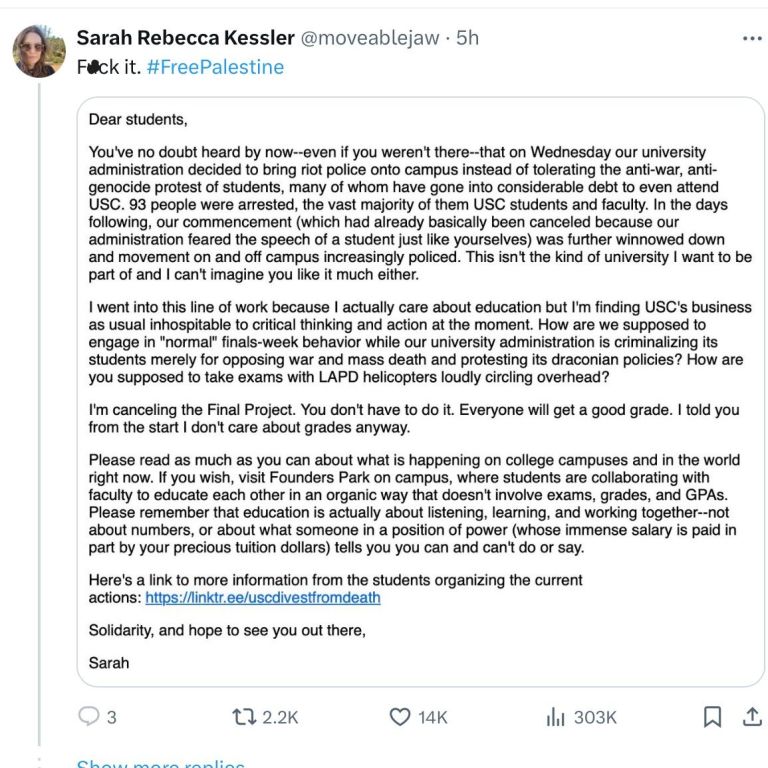

Just for fun, here’s one example of how allowing chaos on campus, and demanding that universities take ideological stands, destroy their academic mission. I don’t want our university to wind up full of faculty like this USC gender-studies professor, whose tweets are now protected (h/t Anna Krylov, who’s at USC). Kessler is using the demonstrations to destroy her mission of educating by canceling their final project and promising that she’ll give all her students a good grade. She’s doing this clearly because she’s pro-Palestinian, as well as a chowderhead (see more here).

Oh, and USC has canceled graduation.

Finally, some advice to Columbia University:

a. If the protestors return, as they have, continue to arrest and suspend them. Your actions have been inconsistent, and that prolongs the demonstrations.

b. DO NOT NEGOTIATE with the protestors.