Just recently Ayaan Hirsi Ali announced, after years of professing atheism (and rejecting her earlier Muslim faith(, that she’d become a Christian. This was announced in an article in Unherd, but she also discussed it briefly on a video, both of which I posted.

Although she wasn’t explicit about what exactly she believed about Christianity, it’s clear that it has something to do with Jesus, for otherwise she’d be a Jew, and in her latest answer to her critics (below), she does mention Jesus, though she remains silent on the crucial issues of whether he was the son of God, was reincarnated, or did miracles—or even existed!

She gave several reasons for her conversion. First, she said, it is only the values of Judeo-Christian western society that will enable us to stave off malign forces like Islamism and Putin’s authoritarian anmbition, as well as the threat of Chinese Communism. She considered atheism to be “too weak and divisive a doctrine to fortify us against our menacing foes.”

But of course atheism simply doubts or denies the existence of Gods, and isn’t meant to help fortify us against our foes. But it is connected with a philosophy that does: secular humanism, which can give us a ground for morality without any need to believe in the supernatural. This is among the many good responses to Hirsi Ali’s arguments given by Michael Shermer in the article below on his Skeptic Substack (click to read):

Like Steve Pinker in Enlightenment Now, Shermer touts secular humanism as not only a good substitute for a god-based morality, but as a major factor responsible for moral and material progress in the last few centuries. Shermer:

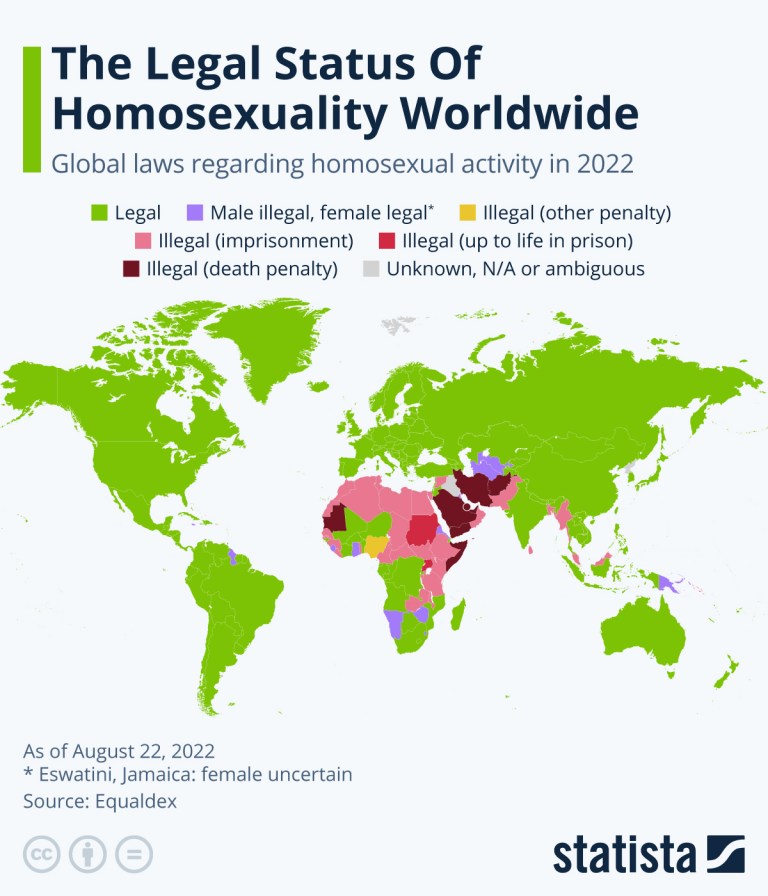

As for Christianity, since Ayaan has declared her fielty to that particular faith over all others, I will concede her point that on the three threats facing the West that concern her (and me)—(1) the authoritarianism/expansionism of Islamism, (2) China and Russia, and (3) woke ideology—Christian conservatives have a clearer vision than atheist (or even theist) Leftists about the threat that Islamism, China and Russia, and woke ideology pose to the West (including and especially the LGBTQ community that would not fare well under such regimes). But this is political pragmatism pure and simple—“Say what you want about Christian conservatives, at least they know what a woman is!” I’m sympathetic to the sentiment, but is it a basis for a worldview? I think not. We should believe things because they are true, not just because they are politically pragmatic.

Consider what’s on demand in Christianity—that Jesus was the Messiah, was crucified, and was resurrected from the dead. (As the apostle Paul said in 1 Cor. 15:13-19: “if there is no resurrection of the dead, then Christ is not risen. … And if Christ is not risen, your faith is futile; you are still in your sins!”) Is that true? My first question is this: Why don’t Jews accept the resurrection as real, either in Jesus’ time or in ours? Jews believe in the same God as Christians. They accept the same holy book as Christians do (the Hebrew Bible, or Old Testament). They even believe in the Messiah. They just don’t think the carpenter from Galilee was him. Jewish rabbis, scholars, philosophers, and historians all know the arguments for the resurrection as well as Christian apologists and theologians, and still they reject them. That’s telling.

And this was my main objection to Hirsi Ali’s switch to Christianity, for, if she’s really a Christian rather than just a secularist adopting “Judeo-Christian values”, it more or less means that she accepts the truths of Christian doctrine, which are summarized in the Nicene Creed (son of God, resurrection, salvation, and so on). Does she believe any of that? She doesn’t say.

Instead, she asks us to accept her Christianity as a response to personal insecurity: a Linus’s blanket of faith. Several readers and friends have said, “Why don’t you leave Hirsi Ali alone, as she’s not proselytizing, only choosing what brings her comfort—and what gives her “meaning and purpose”. As she said:

Yet I would not be truthful if I attributed my embrace of Christianity solely to the realisation that atheism is too weak and divisive a doctrine to fortify us against our menacing foes. I have also turned to Christianity because I ultimately found life without any spiritual solace unendurable — indeed very nearly self-destructive. Atheism failed to answer a simple question: what is the meaning and purpose of life?

Of course the answer to that is that not only can you find meaning and purpose without God (it’s what you choose to embrace in your life, like children, work, music, and so on), but a religiously-based purpose doesn’t go far beyond saying, “My purpose is to adhere to the teachings of the church.” Hirsi Ali, who goes to church, implies that her beliefs are a work in progress:

Of course, I still have a great deal to learn about Christianity. I discover a little more at church each Sunday. But I have recognised, in my own long journey through a wilderness of fear and self-doubt, that there is a better way to manage the challenges of existence than either Islam or unbelief had to offer.

But if you put your beliefs out there, publishing them in a place where you know others will read them, then you open yourself up to criticism and discussion. Nobody doubts Hirsi Ali’s bravery: her books and her movie “Submission,” , the latter criticizing Islam’s treatment of women (which led to the murder of Theo van Gogh and Hirsi Ali’s need to use safe houses and personal security). But, like all of us, if she makes public statements of her beliefs, then she’s not immune from examination and criticism. That’s what Shermer did, and so does Richard Dawkins in a new post on his Substack (click below, and subscribe if you read regularly).

In the video above, Hirsi Ali argues that Dawkins, because of his love of liturgical music, “is one of the most Christian people [she] knows” (48:18). Well, Richard couldn’t let that rest, and wrote a gracious letter to Ayaan which not only denies that he’s a Christian, but denies that Hirsi Ali is a Christian:

As you know, you are one of my absolutely favourite people but . . . seriously, Ayaan? You, a Christian? You are no more a Christian than I am. I might agree with you (I actually do) that Putinism, Islamism, and postmodernish wokery pokery are three great enemies of decent civilisation. I might agree with you that Christianity, if only as a lesser of evils, is a powerful weapon against them. I might add that Christianity has been the inspiration for some of the greatest art, architecture and music the world has ever known. But so what? I once got into trouble for extolling the beauty of Winchester Cathedral bells by comparison with the “aggressive-sounding” yell of “Allahu Akhbar” (the last thing you hear before the bomb goes off, or before your head rolls away from your body). I might agree (I think I do, although certainly not in its earlier history) that Christianity is morally superior to Islam. I might even agree that Christianity is the bedrock of our civilisation (actually I don’t, but even if I did . . .) None of that comes remotely even close to making me – or you – a Christian.

Indeed, as I (and Dawkins and Shermer) immediately recognize, Christianity is a matter of belief, not behavior, regardless of where you think your good behaviors come from. And so, Richard argues, if you act like a Christian and behave like a Christian (i.e., are empathic, nice, and altrustic), that is still irrelevant to whether you are a Christian:

But Ayaan, that is so wrong. How you, or I, behave is utterly irrelevant. What matters is what you believe. What matters is the truth claims about the world which you think are true.

For that is the whole point. Christianity makes factual claims, truth claims that Christians believe, truth claims that define them as Christian. Christians are theists. They believe in a divine father figure who designed the universe, listens to our prayers, is privy to our every thought. You surely don’t believe that? Do you believe Jesus rose from the grave three days after being placed there? Of course you don’t. Do you believe Jesus was born to a virgin? Certainly not. Someone of your intelligence does not believe you have an immortal soul, which will survive the decay of your brain. Christians believe in a frightful place called Hell, where the souls of the wicked go after they are dead. Do you believe that? Hell no! Christians believe every baby is “born in sin” and is saved from Hell only by the redemptive (pre-emptive in the case of all those born anno domini) execution of Jesus. Do you believe anything close to that nasty scapegoat theory? Of course you don’t.

Ayaan, you are no more a Christian than I am.

That may be true, though Hirsi Ali still hasn’t stated what she believes, and it would be good if she did. But of course that would open up a whole can of worms. I, for one, would like to ask her, “If you’re always linking Judaism and Christianity as the source of “Judeo-Christian values,” when why aren’t you a Jew?” The repeated mention of Jesus surely means that she believe something about Christ in particular, though we don’t know exactly what beyond the dubious claim that he existed. But if she starts talking about miracles, crucifixion (some call it “crucifiction”) and resurrection, she loses a considerable amount of credibility among rationalists, for she’s believing in things based on what makes her feel good, regardless of the evidence.

Richard goes on to dispel the idea that there’s no meaning and purpose in life without Christianity. You can read that for yourself, as the article is free.

Finally Hirsi Ali has answered some of her critics in this interview on Unherd with Freddie Sayers, but if you click below you’ll see it’s paywalled. A friend sent me a transcript, and I’ll quote only briefly from it. You might be able to find the article archived, but that failed for me.

In the piece, that I hope will be made public, Hirsi Ali argues that while Jewish and Christian religious schools should remain open, Muslim schools should be closed. This will of course get her in trouble with the First Amendment crowd, or those who believe in simple fairness. And then she explains the personal reason she embraced Christianity (notice the reference to Christ):

FS: A lot of people were also questioning what appeared to be the practical argument for your faith decisions. The argument felt more like a justification of Christianity as a mechanism to resist cultural collapse; it was not so much a personal journey, not so much about your own faith. Is there anything that you would expand on there?

AHA: Yes, it is a very personal story. I don’t know to what extent it’s useful, but on a very personal level, I went through a period of crisis — very personal crisis: of fear, anxiety, depression. I went to the best therapists money can buy. I think they gave me an explanation of some of the things that I was struggling with. But I continued to have this big spiritual hole or need. I tried to self-medicate. I tried to sedate myself. I drank enough alcohol to sterilise a hospital. Nothing helped. I continued to read books on psychiatry and the brain. And none of that helped. All of that explained a small piece of the puzzle, but there was still something that I was missing.

And then I think it was one therapist who said to me, early this year: “I think, Ayaan, you’re spiritually bankrupt.” And at that point, I was in a place where I had sort of given up hope. I was in a place of darkness, and I thought, “well, what the hell, I’m going to open myself to that and see what you are talking about”. And we started talking about faith, and belief in God, and I explained to her that the God I grew up with was a horror show. He created you to punish you and frighten you; and as a girl, and as a woman, you’re just a piece of trash. And so I explained to her why I didn’t believe in God — and, more than that, why I actually hated God. And then she asked me to design my own God, and she said, “if you had the power to make your own God, what would you do?” And as I was going on I thought: that is actually a description of Jesus Christ and Christianity at its best. And so instead of inventing yet another new God, I started diving into that story.

And so far I like this story, as I explore it. The more I look at it, the more I — I don’t want to say I’m fulfilled, but I no longer have this need, this void. I feel like I’m going somewhere. There are standards that I have to live by that are quite high, and that’s daunting. But these are standards that I’d rather aspire to, even if I fail. Maybe the only human being who nearly achieved that was the late Queen Elizabeth! Trying to emulate her is this daily practice of hardship.

Based on this, people will say, “Well, Jesus is better than drink,” and it’s clear that she found Christianity after going through a dark night of the soul. But it’s still fair to ask, “What exactly is ‘Jesus Christ and Christianity at its best'”? as well as “Well, what do you really believe about Jesus and Christianity?” “Do you care that its tenets are true?” And so on à la Dawkins and Shermer. She asks “for respect for her very subjective experience,” but while all of us respect Hirsi Ali as a person, there’s no requirement to respect someone’s beliefs—particularly when she has now written two articles about them and exposed their problems.

I’ll give one more excerpt in which Sayers tries weakly to pin her down about the evidence for Christianity. Here’s that Q&A:

Question 9: Do you believe that we were created by the Abrahamic God? And if you do, have you always believed that’s the case, and simply changed the flavour of that belief over time? If you don’t, is this more a sense of political pragmatism?

AHA: My atheist friends want to see evidence. You say, “Do you believe that God created…?” And then you say, “Well, have you got any evidence for God?” I want to sidestep that question by saying: I believe they are stories, and I choose to believe the story that there is a higher power. What that means I’m still developing, I’m still learning as much as I can. But I choose to believe in that story because the legacy of that story is what we’re living through. So yes, it’s partly pragmatic. And yes, it is partly personal and spiritual. And it’s a story I like because it’s a story that says: human life is worth living because it’s in the image of God. And instead of seeking a God somewhere out there who’s ordering you to do all sorts of things, God is something in you. That’s much, much more appealing to me than the story of: there is nothing there, you have no more value than mould. And that’s atheism. And I think if you tell people they have no more value than mould, then what’s the point?

Here Hirsi Ali explicitly sidesteps the question of evidence and avers that she simply likes the story of Christianity; it gives her solace. But then, with the claim that “God is something in you”, and may not exist at all, we’re back to Richard’s assertion about why she considers herself a Christian. If you simply aspire to be nice, caring, altruistic, and so on, then you might as well say you’re a secular humanist, because secular morality can simply be renamed “God in you,” apparently allowing you to say you’re a Christian.

As for atheism not giving us meaning and purpose in life, yes, of course that’s true. How could it, since it’s simply a disbelief in gods? But once again Hirsi Ali sees atheism as the only alternative to Christianity, completely neglecting secular humanism. After reading the interview, I conclude that Hirsi Ali is in some kind of perplexing trap in which she renames the humanistic instinct “Christianity” and, over time, is learning how to refashion the “god inside her.”

On the other hand, why Christianity rather than Judaism? Sayers doesn’t press the point, for Hirsi Ali would just say, “I don’t know what I believe about the literal truth of Christianity, and I don’t really care. I just like the story because it soothes me.” And there is no answer to that save to say that “well, whatever floats your boat.” It would be delightful to know how Hitchens would answer this.

There are two more pieces that have just come out criticizing Hirsi Ali’s embrace of Christianity, but I won’t discuss them. Here’s a long one by Joseph Klein at Reality’s Last Stand (click to read):

And a shorter one by Freddie deBoer (again, click to read; h/t Steve):

deBoer, too, goes after Hirsi Ali for finding comfort in something for which there’s no evidence. And Remember Victor’s Stenger’s claim that “absence of evidence is evidence of absence if the evidence should be there”? But the evidence is not there, and the priors that there is no God keep increasing. deBoer:

But as you’d expect, my real interest lies in this now-unremarkable acceptance of purely instrumentalized religion. Though their ends are not the same, Haidt and Hirsi Ali share the status of embracing religion purely as a means to those ends. We lack meaning, we lack community, in the past religion has (or so the story goes) inspired meaning and facilitated community. ERGO, we need religion! Is there a God? Was Moses his messenger? Was Jesus his son? (Excuse me, Son.) Was Mohammad his prophet? Are the Shaivites right about the three-headed dominion of the Trimurti, or do the Puranas describe only various forms of Vishnu? Why did Bodhidharma come from the West? To the religious consequentialists, this is all fine print. As I will not stop saying, in its own way this is a bigger insult to religion than anything Richard Dawkins could cobble together; it treats religion as less than wrong. Dawkins and those like him evaluate the truth claims of the world’s religions and say, no, these are not correct. Hirsi Ali is so busy marching towards Armageddon that she scarcely has time to get to know what the truth claims of Christianity even are. New Atheism, truly a dead letter in 2023, took religion immensely seriously. Those who instrumentalize religion do not, and they don’t even arrange themselves on a field of argumentative contestation where that fact could be pointed out.

. . . Why do religions comfort? They comfort because the stories they tell involve divine beings who know everything and who can, often, save us all from the horror of death. We live in a world of intractable and painful moral questions that we feel that we can never resolve; religion says that there are divine beings who know the right answers, and that’s comforting. We miss our loved ones who have died terribly; many religions say that we will one day be reunited with them, and that’s comforting. We’re terrified of death and the prospect of our inevitable non-existence, if we’re being honest; religions offer various ways in which we can escape that awful fate and thus, maybe, the fear. The point is that I get why religion is comforting and offers meaning and solace in a cold world, under the belief that God/gods are real. If you think God’s magic exists, if you think that divine justice exists, then yeah, sure, I get going to church. Sadly, divine justice does not exist because there is no old guy living in the clouds deciding what’s good and what’s bad and controlling everything and being everything but also letting pain and evil exist for some reason. If you disagree with me, though, I get chasing the certainty and the meaning and the belief. If you agree with me that there’s no God, though, and you still want people to go to church because eating bread and drinking grape juice together is good for our cortisol levels, brother… I don’t know. Why not urge people to get into Dungeons & Dragons instead? In what sense is that a less meaningful version of indulging a fantasy?

In the end, why does it matter that Hirsi Ali chooses to call herself a Christian because it fills the God-shaped hole that used to be filled with booze? It matters because she was an idol of many for giving up Islam because of its inimical consequences and poor treatment of humans, and embraced atheism because there was no evidence for Allah. Didn’t she realize that there was equally little evidence for Judaism or Christianity?

It matters because others may also now reject atheism on the grounds that they find Christianity comforting, regardless of the lack of evidence for its tenets.

It matters because the rejection of rationality in favor of comforting stories means the withering away of our organs of reason. And that can only cause trouble in the world.

If you dispense with the need for reason, and choose to believe in what you find comforting or mentally compatible, then you open the Pandora’s Box of unreason that is the basis for at least one malign influence: wokeness. Believing in God because it makes you feel good is not much different in believing that “sex is a spectrum” because it aligns with your gender ideology. One tenet of the Enlightenment is that if you’re faced with a choice of beliefs, you choose the one supported by the most evidence. That’s also how science, one of the best products of the Enlightenment, works too.

***********

UPDATE: Now Andrew Sullivan has joined the critics. Click to see if you can read it:

Sullivan, of course, being a Catholic, is softer on faith than the critics above, but he’s still not so keen on the manner of Hirsi Ali’s conversion. One excerpt:

And Ayaan is right that Western elites have been far too sanguine about the collapse of Christianity in the West, and have overlooked its role in inculcating the virtues essential for liberal society to work. The God-shaped hole left by Christianity’s demise has been filled by the cults of Trump and wokeness, or the distractions of mass entertainment and consumption, in our civilizational heap of broken images.

All of which is well taken. But none of it is a reason for an individual soul to convert to Christianity. Such a person would be more suitable, perhaps, as Zohar Atkins writes, for converting to Judaism, which is more based on earthly goals and achievements. But for a Christian? Jesus rejected exactly that kind of Judaism (which is why anyone who uses the term “Judeo-Christian,” as Ayaan does, misses the entire point). Ross Douthat, in turn, notes the absence of supernatural magic in Ayaan’s vision, key to his view of Christianity, even in post-modernity. Shadi Hamid is even more dismissive toward what he sees as “political conversions”: