In today’s politically polarized country, however, the notion that standardized tests are worthless or counterproductive has become a tenet of liberalism. It has also become an example of how polarization can cause Americans to adopt positions that are not based on empirical evidence. —David Leonhardt

Glory be—the New York Times has published an article that should put to rest a fundamental tenet of wokeness: that standardized tests are socially harmful because they don’t help predict college or later-life success, and also discriminate against racial minorities. In fact, they turn out to be the best single predictor of success regardless of ethnicity or socioeconomic status, according to NYT columnist and author David Leonhardt (a Pulitzer winner). Nor are they “racist” in any way that is meaningful, so racial gaps in college admissions cannot be imputed to the nature of standardized tests. Those tests are, in fact, much better predictors of school and life success than are grade point averages.

I’ve put a quote from Leonhardt above to show how ingrained this idea has become among “progressives” (a point he repeatedly notes). There are several lessons from his piece, which is based on substantial data. Here’s my summary which is mine. And here it is (it’s coming now):

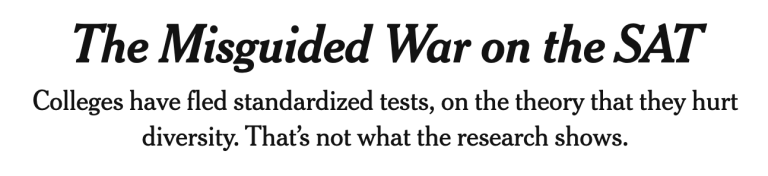

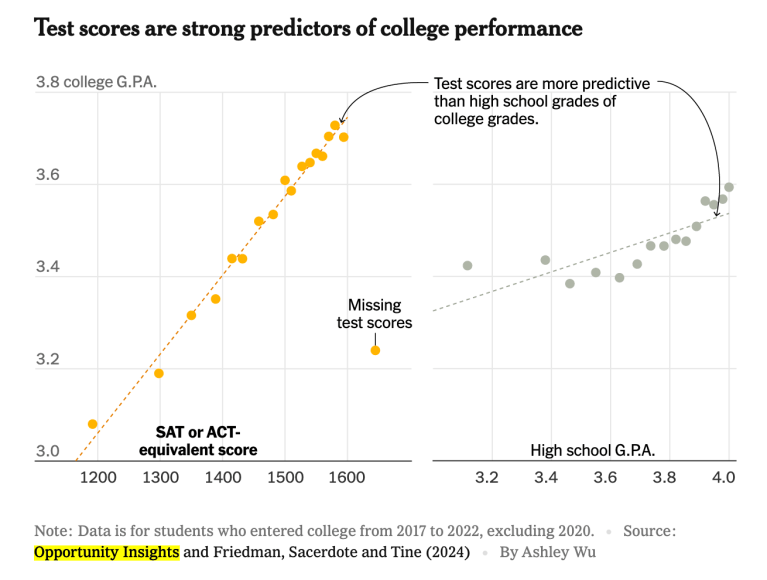

1.) Standardized tests have repeatedly been shown to be the best single predictor of “success”, not only in college grade-point averages, but of the ability to get into a good graduate school and of the likelihood of being hired by a “desirable company”.

2.) Grade-point averages (GPAs), which many tout as being a better replacement for standardized tests, are not nearly as tests like the SAT for predicting “success” as defined above. This is largely because GPAs have steadily risen due to grade inflation, so they don’t carry the discriminatory power of standardized tests.

3.) Contrary to progressive opinion, the tests don’t appear to be “racist.” Further, the correlation between GPA and success is just as high for students coming from “disadvantaged” schools as those from “advantaged” schools. For a given SAT score, your average GPA is going to be the same regardless of whether your parents were rich or poor.

4.) The debate about the value of SATs doesn’t apply to most colleges, in which the majority of applicants are admitted. Rather, it centers on “elite colleges” (Leonhardt names Harvard, MIT, Williams, Carleton, UCLA, and the University of Michigan. These are colleges that most pride themselves on being meritocratic, though they are of course also concerned with diversity.

5.) Many colleges and universities have gotten rid of standardized tests like the SAT on the grounds that they keep minority students out and reduce “equity.” This is the case if tests are the only criterion used for admission. However, by adding criteria like “overcoming adversity”, one can achieve more racial balance (MIT is Leonhardt’s example of this). One reason is that tests can help identify promising students from minority groups who might otherwise be overlooked because they’re from schools that aren’t well known or because they have mediocre grade-point averages.

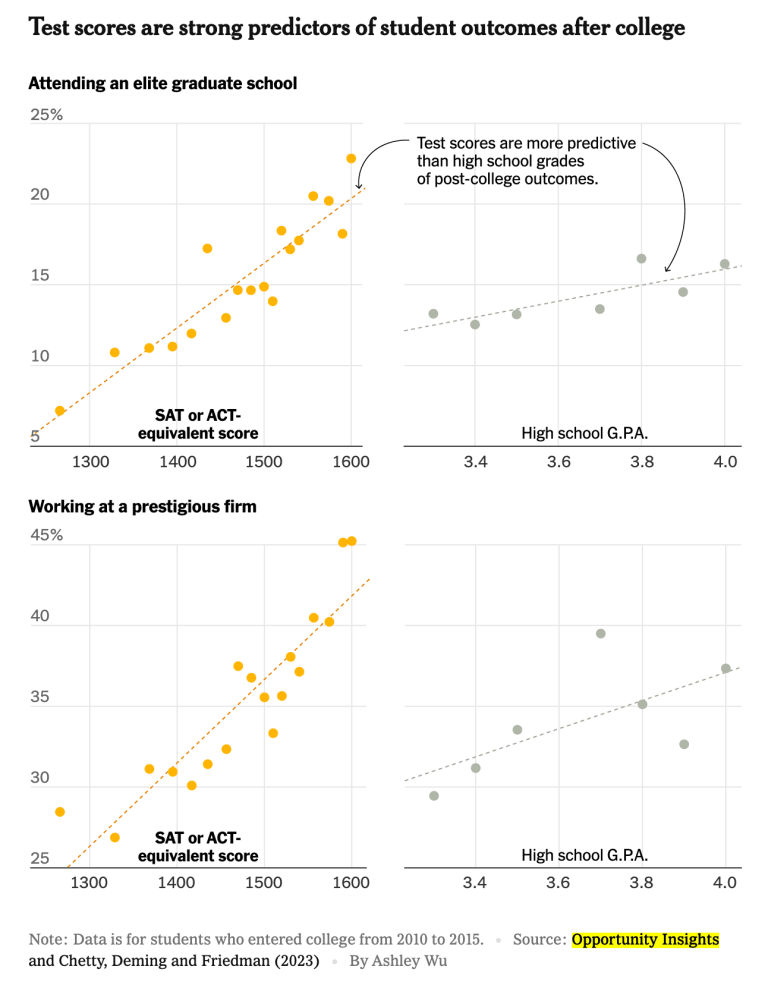

6.) Around 40% of Americans, regardless of ethnicity, think standardized tests should be a major factor in college admissions. Around 45% think it should be a minor factor, and 10-20% think it should not be a factor at all.

The lesson is that the progressives have been wrong: SATs are not only the most useful way to predict both college and life success for applicants, but, when used as part of a mixed-criteria system, can also help achieve greater racial balance. The many schools that have ditched such tests on the grounds of equity need to reinstate them. My own view is that SATs should be mandatory but that other criteria, based not on simple race but on things like “overcoming adversity” (for which there are many signs: socioeconomic class, being handicapped, and so on) should be used, and together these may get us where we want.

You can read the article by clicking below, or find it archived here.

I’ve divided the content into short sections for your ease in reading (or read the original). Headings are mine, excerpts from Leonhardt’s piece are indented

Why tests were deep-sixed:

After the Covid pandemic made it difficult for high school students to take the SAT and ACT, dozens of selective colleges dropped their requirement that applicants do so. Colleges described the move as temporary, but nearly all have since stuck to a test-optional policy. It reflects a backlash against standardized tests that began long before the pandemic, and many people have hailed the change as a victory for equity in higher education.

. . .When I have asked university administrators whether they were aware of the research showing the value of test scores, they have generally said they were. But several told me, not for quotation, that they feared the political reaction on their campuses and in the media if they reinstated tests. “It’s not politically correct,” Charles Deacon, the longtime admissions dean at Georgetown University, which does require test scores, has told the journalist Jeffrey Selingo.\

In 2020, the University of California system went further than most colleges and announced — despite its own data showing the predictive value of tests — that it would no longer accept test scores even from applicants who wanted to submit them. In recent months, I made multiple requests to discuss the policy with university officials. They replied with an emailed statement saying that “U.C. remains committed to maintaining a fair admissions process that reviews every applicant in a comprehensive manner and endeavors to combat systemic inequities.” University spokespeople declined to discuss the policy by telephone or to schedule an interview with an administrator.

This is part of the eternal conflict between universities seen as meritocratic institutions and universities seen as institutions engaged in social engineering by creating equity among their students. The goals are in conflict for sure, but according to Leonhardt a mixed-criterion strategy can achieve a decent compromise. If this has satisfied MIT’s administration (see below), as it has, then it’s ok by me.

Leonhardt’s summary of why we need tests:

Now, though, a growing number of experts and university administrators wonder whether the switch has been a mistake. Research has increasingly shown that standardized test scores contain real information, helping to predict college grades, chances of graduation and post-college success. Test scores are more reliable than high school grades, partly because of grade inflation in recent years.

Without test scores, admissions officers sometimes have a hard time distinguishing between applicants who are likely to do well at elite colleges and those who are likely to struggle. Researchers who have studied the issue say that test scores can be particularly helpful in identifying lower-income students and underrepresented minorities who will thrive. These students do not score as high on average as students from affluent communities or white and Asian students. But a solid score for a student from a less privileged background is often a sign of enormous potential.

“Standardized test scores are a much better predictor of academic success than high school grades,” Christina Paxson, the president of Brown University, recently wrote. Stuart Schmill — the dean of admissions at M.I.T., one of the few schools to have reinstated its test requirement — told me, “Just getting straight A’s is not enough information for us to know whether the students are going to succeed or not.”

An academic study released last summer by the group Opportunity Insights, covering the so-called Ivy Plus colleges (the eight in the Ivy League, along with Duke, M.I.T., Stanford and the University of Chicago), showed little relationship between high school grade point average and success in college. The researchers found a strong relationship between test scores and later success.

Likewise, a faculty committee at the University of California system — led by Dr. Henry Sánchez, a pathologist, and Eddie Comeaux, a professor of education — concluded in 2020 that test scores were better than high school grades at predicting student success in the system’s nine colleges, where more than 230,000 undergraduates are enrolled. The relative advantage of test scores has grown over time, the committee found.

“Test scores have vastly more predictive power than is commonly understood in the popular debate,” said John Friedman, an economics professor at Brown and one of the authors of the Ivy Plus admissions study.

The data on the predictive power of tests.

First, test scores themselves are very good predictors of college GPA, much better than are high-school GPAs (the regression of college GPA is much stronger and tighter in the former than in the latter case). The graph below shows that.

Here’s a plot showing the correlation between SAT scores (the test is taken in high school) and college GPAs, separated by “advantaged” vs. “disadvantaged” high school (the division is apparently made not by race, but by socioeconomic class, though I’m not sure). Note that for a given GPA, it doesn’t matter whether you’ve come from an advantaged vs. disadvantaged school—your predicted GPA is about the same. That means that, if you choose students solely on how their college grades will turn out, you should go solely by standardized test scores and not by “advantaged” or “disadvantaged” educations. But of course there are other measures of “success” that we’ll see below, measures that haven’t been assessed by dividing up the students by their “advantage”:

If your sole criterion for “success” is college GPA, you don’t need to take into account “advantage” or “disadvantage” educations, whether the sign of that be race, socioeconomic class, or reputation of the school. But there are other criteria for success, like the two below. Both are highly correlated with SAT (or ACT-equivalent) scores, but the outcomes haven’t been separated by socioeconomic class or race. It is possible that “overcoming adversity” could add to the predictability for getting into grad school or getting a good job above just using SAT scores. (Click to enlarge all graphs.)

It’s possible that if you had an expansive definition of “advantaged” education, which surely relies somewhat on socioeconomic class but also on other types of potential disadvantages (physical handicaps are one, but there are others), you could show that disadvantaged students with the same SAT score as advantaged students would nevertheless do better in life. Or, if you prize some kind of “experiential diversity” or “thought diversity” in colleges, then you might want to use criteria other than SAT scores or grades. In fact, that’s what many college-admissions essays are about: “Tell us about your life—what you’ve done, have you done anything unusual” etc. etc.

As far as rich white kids being able to do better because they can afford tutoring, music lessons and the like, Leonhardt says this with regard to the inequities that do exist among racial admissions:

The [SAT-like] tests are not entirely objective, of course. Well-off students can pay for test prep classes and can pay to take the tests multiple times. Yet the evidence suggests that these advantages cause a very small part of the [racial] gaps.

It’s a long article, but the point is this: SATs predict a lot about success, but there are still huge inequities among races in how they do, though that’s more a problem for elite schools than non-elite ones. If we’re concerned about more than just merit, but in things like thought diversity, experiential diversity, and (in my view) educational reparations, then what can we do?

First, here are the data on different ethnic groups in America, and how they think standardized tests should be counted in college admissions. It’s not that different among groups:

What is the solution to get students who will succeed while maintaining a decent racial balance?

We can use a “mixed strategy”:

But the data suggests that testing critics have drawn the wrong battle lines. If test scores are used as one factor among others — and if colleges give applicants credit for having overcome adversity — the SAT and ACT can help create diverse classes of highly talented students.

This has apparently worked at MIT, which dropped the test requirement for a couple of years and then reinstated it. The reinstatement brought improvement:

M.I.T. has become a case study in how to require standardized tests while prioritizing diversity, according to professors elsewhere who wish their own schools would follow its lead. During the pandemic, M.I.T. suspended its test requirement for two years. But after officials there studied the previous 15 years of admissions records, they found that students who had been accepted despite lower test scores were more likely to struggle or drop out.

Schmill, the admissions dean, emphasizes that the scores are not the main factor that the college now uses. Still, he and his colleagues find the scores useful in identifying promising applicants who come from less advantaged high schools and have scores high enough to suggest they would succeed at M.I.T.

Without test scores, Schmill explained, admissions officers were left with two unappealing options. They would have to guess which students were likely to do well at M.I.T. — and almost certainly guess wrong sometimes, rejecting qualified applicants while admitting weaker ones. Or M.I.T. would need to reject more students from less advantaged high schools and admit more from the private schools and advantaged public schools that have a strong record of producing well-qualified students.

“Once we brought the test requirement back, we admitted the most diverse class that we ever had in our history,” Schmill told me. “Having test scores was helpful.” In M.I.T.’s current first-year class, 15 percent of students are Black, 16 percent are Hispanic, 38 percent are white, and 40 percent are Asian American. About 20 percent receive Pell Grants, the federal program for lower-income students. That share is higher than at many other elite schools.

“When you don’t have test scores, the students who suffer most are those with high grades at relatively unknown high schools, the kind that rarely send kids to the Ivy League,” Deming, a Harvard economist, said. “The SAT is their lifeline.”

Leonhardt ends his piece with the quote at the top, followed by this:

Conservatives do it [ignore the data] on many issues, including the dangers of climate change, the effectiveness of Covid vaccines and the safety of abortion pills. But liberals sometimes try to wish away inconvenient facts, too. In recent years, Americans on the left have been reluctant to acknowledge that extended Covid school closures were a mistake, that policing can reduce crime and that drug legalization can damage public health.

There is a common thread to these examples. Intuitively, the progressive position sounds as if it should reduce inequities. But data has suggested that some of these policies may do the opposite, harming vulnerable people.

In the case of standardized tests, those people are the lower-income, Black and Hispanic students who would have done well on the ACT or SAT but who never took the test because they didn’t have to. Many colleges have effectively tried to protect these students from standardized tests. In the process, the colleges denied some of them an opportunity to change their lives — and change society — for the better.

If there’s any lesson in this, it’s that the “progressives” have been misguided in their call for dropping standardized tests. Doing so causes confusion and also leaves out many worthy students who have no other way of being identified. Standardized tests like the SATs should be required for all students, particularly in “elite” colleges, as a useful form of predicting who will do well and who won’t. But there are other criteria that should be considered, too. Readers are welcome to answer this question:

If you want a pure meritocratic admissions process, one that ensures that students get good grades in college, that can be done by relying almost entirely on SAT scores and not GPAs. But perhaps you’d prefer some criteria beyond those necessary to judge “probablility of success”. If so, what would you look for? (Remember, the Supreme Court has rule that race itself cannot be a criterion for admission.

Tests of any sort are also a great way for individuals to learn. Perhaps the only way.

I add this because, frankly, tests seem stigmatized, generally.

Leonhardt’s 6 points and his analysis is spot on. The SAT should be the primary method for admissions, with GPA, looking at essays and outside interests factored in.

There is a kind of diversity that can usefully be factored in, and that certainly used to be factored in at many selective colleges and universities drawing applicants from schools in Boston, New York and Philadelphia and their suburbs, and from private high schools. That an applicant comes from a high school in rural Michigan (for example) can be factored in. It’s a good thing for kids from good high schools in the east coast cities and from private high schools to share a college experience with kids with a very different background. College admissions departments may reasonably consider this.

During college, I had a part-time job tutoring kids. Since I had scored pretty well on standardized tests, I was put in charge of “test prep”…i.e. helping high school kids improve their ACT/SAT scores.

And…it was extremely difficult. The only students that ever benefitted from our services were kids who were already strong on verbal tests but needed to improve their math/science scores…those kids we could help somewhat.

But students who had poor verbal skills and/or were scoring in the bottom quartile overall were hopeless; it was virtually impossible to get any material improvements.

My takeaway was that these tests are much more than party tricks, and are as much a test of what you have absorbed in a decade or so of schooling up to that point as they are an aptitude test. A few prep courses can’t make up for years of underachievement.

All the preparation any test taker needs can be obtained on the cheap. There are books one can buy (for about $30) that explain the tests in detail (SAT, GRE = Graduate Record exam, for graduate study), and contain lots of sample tests. So the idea that rich parents can give a substantial advantage to their kids by paying for expensive test prep courses is completely false. Such courses can do no more for you than can be achieved by buying a test prep book and then studying it carefully.

Let’s go further: No need to buy a test prep book, go to your local public library and check it out. Public libraries also offer free test prep programs from time to time.

“But perhaps you’d prefer some criteria beyond those necessary to judge “probablility of success”. If so, what would you look for?”

First : all postmodern interpretation of this question should be ruled out.

But it is a great question, that I don’t know how to answer. I think expectation becomes important. Perhaps trajectory — a student starts low, finishes high – seems to matter.

But of course, it doesn’t beat the juggernaut student.

This is an excellent post on an important topic.

The reason why colleges and universities eliminated standardized tests is not because they are inaccurate or ineffective, but precisely because they *are* effective. They eliminated objective measures so they they can apply whatever criteria they like. It’s good to see data brought to bear on this issue, particularly in the NYT, where the article will be widely read.

Yes. Colleges and universities should reinstate SAT scores as the primary criterion of admission. It’s heartless and demoralizing to admit students who will inevitably fail. Starting with SAT scores can ensure that students they admit have a fighting chance of success. Beyond that, there is a range of other criteria to use: community service, evidence of leadership, desire for racial and ethnic diversity, economic diversity, viewpoint diversity, geographic diversity, etc. I have nothing new to add regarding the ancillary criteria that are already in use. But these criteria should be ancillary, not primary. The primary criterion—the one that should be weighted most highly—should be the probably of graduating successfully. This means bringing back the SAT.

The main remaining question is how much each of these criteria are weighted. I would call for a high weighting for the SAT, say, 75%, with the rest taking on lesser weightings. Also, I would really like to see colleges and universities post their criteria and weightings publicly. Students and parents should not be faced with a smokescreen of vagueness when choosing which colleges or universities to attend. “We take a holistic approach” is meaningless and should not be tolerated.

“… not because they are inaccurate or ineffective, but precisely because they *are* effective. […] It’s heartless and demoralizing to admit students who will inevitably fail. ”

^^^^ (bold added.)

If they did this, the percentage of Asian students at elite institutions might approach 70%, which is about what it is at the Stuyvesant High School in NYC. At this school, black students are, gulp, only 1.4% of the student body! Despite political pressure, Stuy still relies primarily on top scores on an objective test to determine who is accepted.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stuyvesant_High_School

I couldn’t give a fig about this, but there is no way Harvard, Yale, or the rest would allow these demographics.

I suggest that administrators of the U. Cal. system scrapped the SAT for a perfectly simple reason: SAT results provide empirical evidence against DEI handwaving. Where the latter procedure used to depend on ignoring the SAT quietly, now the SAT is ignored officially, and so there is nothing to discuss. As the article reports: “University spokespeople declined to discuss the policy by telephone or to schedule an interview with an administrator.”

One problem with Leonhardt’s piece is spotlighted in a hard-hitting news piece from The Onion News Network:

Are Tests Biased Against Students Who Don’t Give A Shit? Sept 2010, 2 mins

lol

Also relevant:

Frederick M. Hess: Why Are Elite Colleges Enabling This Dubious Racket? December 19, 2023

https://www.aei.org/op-eds/why-are-elite-colleges-enabling-this-dubious-racket/

The author has a Ph.d. in political science from Harvard. He is Senior Fellow and Director, Education Policy Studies (at the American Enterprise Institute)

(Quoting the quote): ” “holistic” ”

… dialectic.

Lots of literature with these two ideas in close proximity.

I suggest a tiered, lottery approach. First, the most rigorous schools could set a minimum SAT score for admission, maybe 1350. Second, since those with higher SAT scores are likelier to succeed, schools could scale their charge for courses, such that those with the highest SATs pay the least. Those with lower scores would then need to bite the bullet and work their tails off. Third, schools could waive the higher cost for those with lower scores based on lower socioeconomic status, such that those from working-class backgrounds (e.g., household income $30,000) receive a discount. Fourth, admit only 5 to 10% of applicants from which 75% have super-high SAT scores and 25% have lower SAT scores. Anonymize names in the selection process to prevent inference based on immutable characteristics. Eliminate legacy admissions. Do away with admissions essays, since these are markers of class, race, and political affiliation. Require 80% of admissions be US citizens to avoid over enrichment of students from other counties. Weight first-generation college applicants higher.

State schools could adopt a similar approach with a lower threshold score for admission, and, of course, a more generous admissions rate.

With this lottery approach, some very smart people would end up at state schools, and there would be less political bias at the Ivies.

As Leonhardt points out, contrary to the recommendations of their own expert task force, the University of California dropped standardized tests for admission. The report can be found at here: https://senate.universityofcalifornia.edu/_files/underreview/sttf-report.pdf.

Some pertinent conclusions are:

Test scores [from standardized tests such as the ACT & SAT] are predictive for all demographic groups and disciplines, even after controlling for HSGPA. In fact, test scores are better predictors of success for students who are Underrepresented Minority students (URMs), who are first-generation, or whose families are low-income: that is, test scores explain more of the variance in UGPA and completion rates for students in these groups. One consequence of dropping test scores would be increased reliance on HSGPA in admissions. The STTF found that California high schools vary greatly in grading standards, and that grade inflation is part of why the predictive power of HSGPA has decreased since the last UC study.”

… When added to a statistical model relating first-year GPA to HSGPA, test scores increase predictability of freshman GPA by 29% for Caucasian students, by 60% for Asian students, by 77% for Hispanic students, and by 96% for African- American students. Standardized test scores increase predictability of graduation GPA by 22% for Caucasian students, by 39% for Asian students, by 61% for Hispanic students, and by 56% for African- American students

… Figure 3C-5 (left column, top row) shows even more clearly that UC comprehensive review policy effectively compensates for most group differences in the SAT scores, by plotting the admission rate of each racial/ethnic group by SAT score. It shows that less advantaged racial/ethnic groups are admitted at higher rates for any given SAT score. This finding is inconsistent with claims that UC considered SAT in a way which fails to take into account disadvantage. … To give one striking example: for students with SAT scores of 1000, admission rates are about 30% for whites but roughly 50% for Latino students.

How high do SAT scores need to be for whites to have the same 50% admission rate as Latino students with scores of 1000 do? The answer is that whites do not reach admission rates of 50% until they reach an SAT score of 1200.

How likely is it that the schools that have already dropped them will ever reverse course?

I only got in to UCLA due to SAT scores. Grades from my inner city school were too low. I graduated Magna Cum Laude and got my PhD from UC Berkeley. I gave liberally to both UC schools for most of my lifetime, but since they scrapped the SAT I stopped giving to them.

I knew the value of the SAT from my own experience.

One comment: from this physicist’s seat, the plot which supposedly shows a small gap between “advantaged” and “disadvantaged” ones.. may not demonstrate even that. The fluctuations look too small to make any such claim worth taking seriously. From what is plotted the gap appears to be statistically indistinguishable from zero, unless we want to live in replication-crisis land where one makes “discoveries” thanks to two sigma “signals.”

Oh, let’s just ignore statistical significance, and we can all amuse ourselves with the observation that GPA dips as one approaches a 1600 SAT.

The rumor at Caltech years ago was that GPA was positively correlated with math SAT but that the correlation with verbal SAT was more complicated (and was negative above a certain level).

I’m glad you made that point. In medical research we do settle for two-sigma statistical significance as matter of convention. (It is true that many landmark clinical trials do considerably better than this but then the researchers are accused of making the study unnecessarily large, not stopping soon enough, or of low-balling the hypothesized effect size; the study was “therefore” unethical or wasteful of resources that could have gone to an academic rival’s research.) The two trials of Covid vaccines reported 95% (1.96-sigma) confidence intervals for prevention of infection and did not detect a death-prevention signal. (There were no deaths in control or vaccine arms in either trial. The trials were powered to detect reduction in infection and stopped as soon as infections in both arms combined crossed a stopping barrier. Given that expected case fatality in the samples not vaccinated was < 1% — nursing home residents and people expected to die soon of other causes were excluded — a truly enormous trial would have been needed to reject an H-null of no reduction in deaths even at the modestly ambitious 2-sigma level.)

Nonetheless, the stats textbook I started with was published in 1970* — actually it was my mother's for her grad-school work but I had unusual reading habits for a high-schooler. It operated under the convention that for most social-science research — the focus of the text — statistical significance would usually be 0.01 but, in a pinch, 0.05 might be acceptable. If we have "slipped" to 0.05 routinely without really ever acknowledging it, and I have read sociology papers that rejected H-null at 0.10, then clearly we are going to have a lot of Type 1 errors that will fail replication, if anyone ever even bothers. This is particularly likely for hypotheses that seem not very likely to be true a priori. And that’s all before you look at flaws in study design that make statistical inference unjustified in the first place.

Given the large variances in human samples — larger now because granting agencies want “diverse” samples to improve generalizability for oppressed groups — rejecting H-null at even 2.6 sigma is very expensive, particularly given the small effect sizes expected with modern medical innovations. There aren’t very many slam-bang innovations like antibiotics left to discover; much of what we are finding now is noise in the sampling error or is “life-saving” treatment based on testimonials for which trials are claimed to be unethical.

—————–

* Henry E. Klugh. Statistics: The Essentials for Research. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1970.

https://capitolweekly.net/the-sat-is-helping-minorities-succeed/

The correlation with SAT has been known for decades.

Thanks for this detailed discussion.

Missing words? “are not nearly as tests” in 4th paragraph, i.e. Point #2 in a numbered list of points. Seems that it is meant to say “are not nearly as GOOD AS tests”.

“…In fact, they [SATs] turn out to be the best single predictor of success regardless of ethnicity or socioeconomic status, according to NYT columnist and author David Leonhardt (a Pulitzer winner).” – J. Coyne

Leonhardt’s data might refute him, but according to Michael Sandel (an eminent political philosopher), there is a fly in the ointment, i.e. in the meritocratic ethics of college admission, because…

“From the standpoint of fairness, however, it is hard to distinguish between the “back door” and the “side door.” Both give an edge to children of wealthy parents who are admitted instead of better-qualified applicants. Both allow money to override merit. Admission based on merit defines entry through the “front door.” As Singer put it, the front door “means you get in on your own.” This mode of entry is what most people consider fair; applicants should be admitted based on their own merit, not their parents’ money.

In practice, of course, it is not that simple. Money hovers over the front door as well as the back. Measures of merit are hard to disentangle from economic advantage. Standardized tests such as the SAT purport to measure merit on its own, so that students from modest backgrounds can demonstrate intellectual promise. In practice, however, SAT scores closely track family income. The richer a student’s family, the higher the score he or she is likely to receive.

Not only do wealthy parents enroll their children in SAT prep courses; they hire private admissions counselors to burnish their college applications, enroll them in dance and music lessons, and train them in elite sports such as fencing, squash, golf, tennis, crew, lacrosse, and sailing, the better to qualify for recruitment to college teams. These are among the costly means by which affluent, striving parents equip their progeny to compete for admission.

And then there is tuition. At all but the handful of colleges wealthy enough to admit students without regard for their ability to pay, those who do not need financial aid are more likely than their needy counterparts to get in.

Given all this, it is not surprising that more than two-thirds of students at Ivy League schools come from the top 20 percent of the income scale; at Princeton and Yale, more students come from the top 1 percent than from the entire bottom 60 percent of the country. This staggering inequality of access is due partly to legacy admissions and donor appreciation (the back door), but also to advantages that propel children from well-off families through the front door.”

(Sandel, Michael J. /The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good?/ Dublin: Penguin, 2021. pp. 10-1)

I usually start with the fact that these elite colleges such Harvard and Yale invented the Gentleman’s C grade, since for nearly 300 years they were primarily part of the reproduction of a social class system in which “merit” was not understood to be academic achievement, but simple social class standing.

I’ve been interested in what I might call the social history of merit when it comes to college admissions. One possible starting point might be the end of WWII and the use of the GI Bill to provide social class mobility for veterans: free college as part of the reward for their service; entry into the middle class. Studies of social mobility since the late 1950s, however suggest that the rapid expansion of the middle class stalled for decades, as children of those new middle class parents remained middle class, and fought to maintain barriers to the entry of lower and working class folks into the middle class — and much of that has a racial dimension as well, with, to take only one example, discriminatory housing policies that restricted the ability of minority home buyers to accumulate significant equity that could be converted into, for example, college tuition for their children. My impression is that by the time some of those barriers were being eliminated, a push for the exclusive use of “merit” newly understood as academic achievement began. And so on.

We usually associate the debate with affirmative action and its descendants, such as “diversity.” But I wonder if the dominance of academic “merit” by Asian-Americans is going to produce a backlash among non-Asian White families who are increasingly finding themselves the losers in a game they rigged in favor of themselves in 1944?

“But I wonder if the dominance of academic “merit” by Asian-Americans is going to produce a backlash among non-Asian White families who are increasingly finding themselves the losers in a game they rigged in favor of themselves in 1944?”

It already has. The primary beneficiaries of eliminating the SATs are not people of color, who make up a small portion of the population and therefore can never be a majority at any university, but mediocre white kids with rich parents. No way that Connor or Madison can get into Harvard with their 1300 SAT…but if objective tests are eliminated in favor of being “well-rounded”, they have a chance against Lucy Chen of Queens, NY with her 1590 SAT.

That’s an interesting thought, Jeff. I had, until now, assumed the abandonment of the SAT was part of the relatively recent reluctance to consider it valid, like its close relative the IQ test, because it shows clear racial differences in scores. That is not permitted in the world of the blank slate.

My view is that good brains must not be wasted, no matter what colour skin houses them, or the social class of the owner, and we make inefficient use of the limited number of places at good universities if we give some of them to individuals who show on their SAT they are unlikely to succeed, despite that education. It doesn’t bother me if most of the kids at those schools are Asian or Ashkenazy: human progress benefits in the end. The result is far less beneficial if we fill seats according to quotas, and even worse if we produce graduates in quotas. After all, what is education for? The individual might say personal growth, but policy should be about what works best for society as a whole.

The University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine back in the 1970s looked about like Stuyvesant High School, allowing for the other alternatives for high school that white families presumably have who can afford to live in Manhattan, but who happily send their kids to medical school. In those days, U of T used only the applicant’s undergrad GPA and the score on the science portion of the MCAT (and in today’s age of interviews and personal statements still weights MCAT heavily and race not at all.) No place for “well-rounded” dumb kids in med school, nor in the other professional schools where they drop out, and can do actual harm if they graduate.

And there has been no backlash from well-off white parents*, any more than from wealthy hockey parents who have to resign themselves that their little Bantam isn’t going to make it to the NHL.

——————

* There has been agitation from the smallish black community, resentful that the medical schools have not adopted the American definition of diversity.

I’m glad that no one is lobbying for underqualified people to be doctors.

But Stuy and similar schools were/are under significant pressure to change admissions standards to be “more holistic”, and to weight GPA much higher. This was particularly evident during the reign of progressive mayor DiBlasio.

My point is that although efforts to change the admission standards of places like Stuy tend to be led by people of color (black and latino), mathematically it will be white kids that will benefit most. Again, if schools are supposed to represent the population at large in terms of ethnic/racial distribution, then a majority white country will have a majority white student body.

White parents are effectively using people of color (black and latino) as both a battering ram and a shield for their own interests.

As someone who writes the items for these kinds of tests and develops the forms, I can say we spend a lot of effort on fairness, sensitivity, and bias in order to remove obstacles and give every student the best opportunity to interact with the items and show what they know or their thinking ability.