In today’s politically polarized country, however, the notion that standardized tests are worthless or counterproductive has become a tenet of liberalism. It has also become an example of how polarization can cause Americans to adopt positions that are not based on empirical evidence. —David Leonhardt

Glory be—the New York Times has published an article that should put to rest a fundamental tenet of wokeness: that standardized tests are socially harmful because they don’t help predict college or later-life success, and also discriminate against racial minorities. In fact, they turn out to be the best single predictor of success regardless of ethnicity or socioeconomic status, according to NYT columnist and author David Leonhardt (a Pulitzer winner). Nor are they “racist” in any way that is meaningful, so racial gaps in college admissions cannot be imputed to the nature of standardized tests. Those tests are, in fact, much better predictors of school and life success than are grade point averages.

I’ve put a quote from Leonhardt above to show how ingrained this idea has become among “progressives” (a point he repeatedly notes). There are several lessons from his piece, which is based on substantial data. Here’s my summary which is mine. And here it is (it’s coming now):

1.) Standardized tests have repeatedly been shown to be the best single predictor of “success”, not only in college grade-point averages, but of the ability to get into a good graduate school and of the likelihood of being hired by a “desirable company”.

2.) Grade-point averages (GPAs), which many tout as being a better replacement for standardized tests, are not nearly as tests like the SAT for predicting “success” as defined above. This is largely because GPAs have steadily risen due to grade inflation, so they don’t carry the discriminatory power of standardized tests.

3.) Contrary to progressive opinion, the tests don’t appear to be “racist.” Further, the correlation between GPA and success is just as high for students coming from “disadvantaged” schools as those from “advantaged” schools. For a given SAT score, your average GPA is going to be the same regardless of whether your parents were rich or poor.

4.) The debate about the value of SATs doesn’t apply to most colleges, in which the majority of applicants are admitted. Rather, it centers on “elite colleges” (Leonhardt names Harvard, MIT, Williams, Carleton, UCLA, and the University of Michigan. These are colleges that most pride themselves on being meritocratic, though they are of course also concerned with diversity.

5.) Many colleges and universities have gotten rid of standardized tests like the SAT on the grounds that they keep minority students out and reduce “equity.” This is the case if tests are the only criterion used for admission. However, by adding criteria like “overcoming adversity”, one can achieve more racial balance (MIT is Leonhardt’s example of this). One reason is that tests can help identify promising students from minority groups who might otherwise be overlooked because they’re from schools that aren’t well known or because they have mediocre grade-point averages.

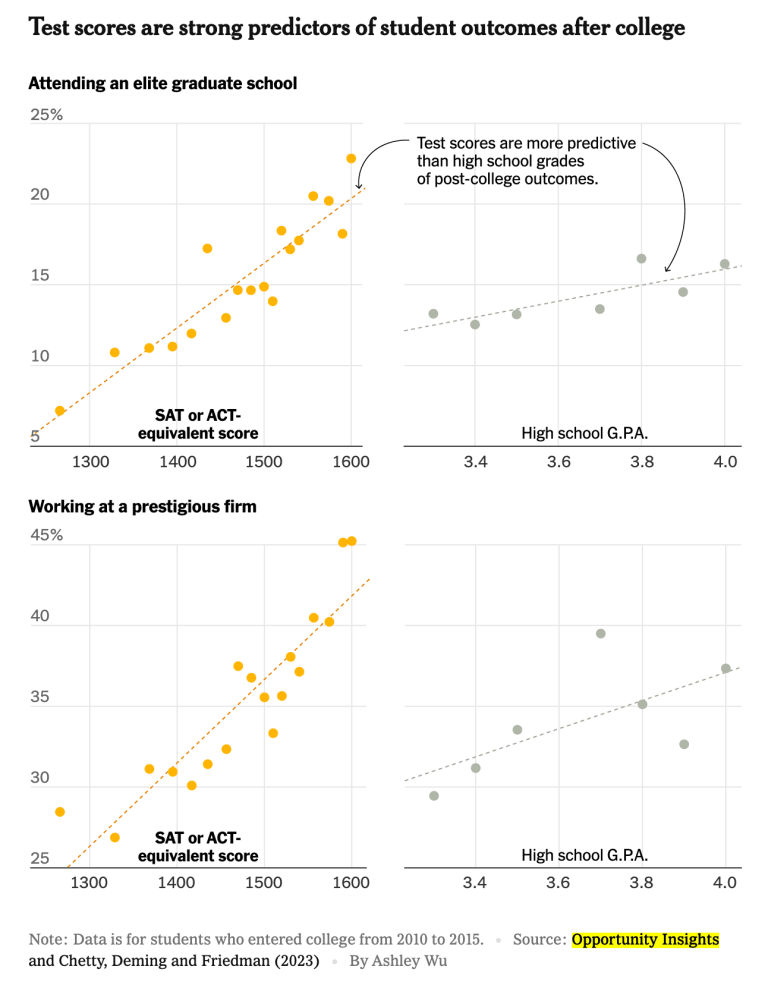

6.) Around 40% of Americans, regardless of ethnicity, think standardized tests should be a major factor in college admissions. Around 45% think it should be a minor factor, and 10-20% think it should not be a factor at all.

The lesson is that the progressives have been wrong: SATs are not only the most useful way to predict both college and life success for applicants, but, when used as part of a mixed-criteria system, can also help achieve greater racial balance. The many schools that have ditched such tests on the grounds of equity need to reinstate them. My own view is that SATs should be mandatory but that other criteria, based not on simple race but on things like “overcoming adversity” (for which there are many signs: socioeconomic class, being handicapped, and so on) should be used, and together these may get us where we want.

You can read the article by clicking below, or find it archived here.

I’ve divided the content into short sections for your ease in reading (or read the original). Headings are mine, excerpts from Leonhardt’s piece are indented

Why tests were deep-sixed:

After the Covid pandemic made it difficult for high school students to take the SAT and ACT, dozens of selective colleges dropped their requirement that applicants do so. Colleges described the move as temporary, but nearly all have since stuck to a test-optional policy. It reflects a backlash against standardized tests that began long before the pandemic, and many people have hailed the change as a victory for equity in higher education.

. . .When I have asked university administrators whether they were aware of the research showing the value of test scores, they have generally said they were. But several told me, not for quotation, that they feared the political reaction on their campuses and in the media if they reinstated tests. “It’s not politically correct,” Charles Deacon, the longtime admissions dean at Georgetown University, which does require test scores, has told the journalist Jeffrey Selingo.\

In 2020, the University of California system went further than most colleges and announced — despite its own data showing the predictive value of tests — that it would no longer accept test scores even from applicants who wanted to submit them. In recent months, I made multiple requests to discuss the policy with university officials. They replied with an emailed statement saying that “U.C. remains committed to maintaining a fair admissions process that reviews every applicant in a comprehensive manner and endeavors to combat systemic inequities.” University spokespeople declined to discuss the policy by telephone or to schedule an interview with an administrator.

This is part of the eternal conflict between universities seen as meritocratic institutions and universities seen as institutions engaged in social engineering by creating equity among their students. The goals are in conflict for sure, but according to Leonhardt a mixed-criterion strategy can achieve a decent compromise. If this has satisfied MIT’s administration (see below), as it has, then it’s ok by me.

Leonhardt’s summary of why we need tests:

Now, though, a growing number of experts and university administrators wonder whether the switch has been a mistake. Research has increasingly shown that standardized test scores contain real information, helping to predict college grades, chances of graduation and post-college success. Test scores are more reliable than high school grades, partly because of grade inflation in recent years.

Without test scores, admissions officers sometimes have a hard time distinguishing between applicants who are likely to do well at elite colleges and those who are likely to struggle. Researchers who have studied the issue say that test scores can be particularly helpful in identifying lower-income students and underrepresented minorities who will thrive. These students do not score as high on average as students from affluent communities or white and Asian students. But a solid score for a student from a less privileged background is often a sign of enormous potential.

“Standardized test scores are a much better predictor of academic success than high school grades,” Christina Paxson, the president of Brown University, recently wrote. Stuart Schmill — the dean of admissions at M.I.T., one of the few schools to have reinstated its test requirement — told me, “Just getting straight A’s is not enough information for us to know whether the students are going to succeed or not.”

An academic study released last summer by the group Opportunity Insights, covering the so-called Ivy Plus colleges (the eight in the Ivy League, along with Duke, M.I.T., Stanford and the University of Chicago), showed little relationship between high school grade point average and success in college. The researchers found a strong relationship between test scores and later success.

Likewise, a faculty committee at the University of California system — led by Dr. Henry Sánchez, a pathologist, and Eddie Comeaux, a professor of education — concluded in 2020 that test scores were better than high school grades at predicting student success in the system’s nine colleges, where more than 230,000 undergraduates are enrolled. The relative advantage of test scores has grown over time, the committee found.

“Test scores have vastly more predictive power than is commonly understood in the popular debate,” said John Friedman, an economics professor at Brown and one of the authors of the Ivy Plus admissions study.

The data on the predictive power of tests.

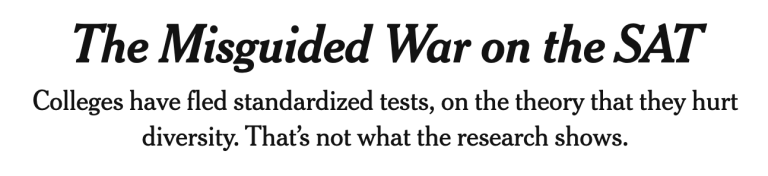

First, test scores themselves are very good predictors of college GPA, much better than are high-school GPAs (the regression of college GPA is much stronger and tighter in the former than in the latter case). The graph below shows that.

Here’s a plot showing the correlation between SAT scores (the test is taken in high school) and college GPAs, separated by “advantaged” vs. “disadvantaged” high school (the division is apparently made not by race, but by socioeconomic class, though I’m not sure). Note that for a given GPA, it doesn’t matter whether you’ve come from an advantaged vs. disadvantaged school—your predicted GPA is about the same. That means that, if you choose students solely on how their college grades will turn out, you should go solely by standardized test scores and not by “advantaged” or “disadvantaged” educations. But of course there are other measures of “success” that we’ll see below, measures that haven’t been assessed by dividing up the students by their “advantage”:

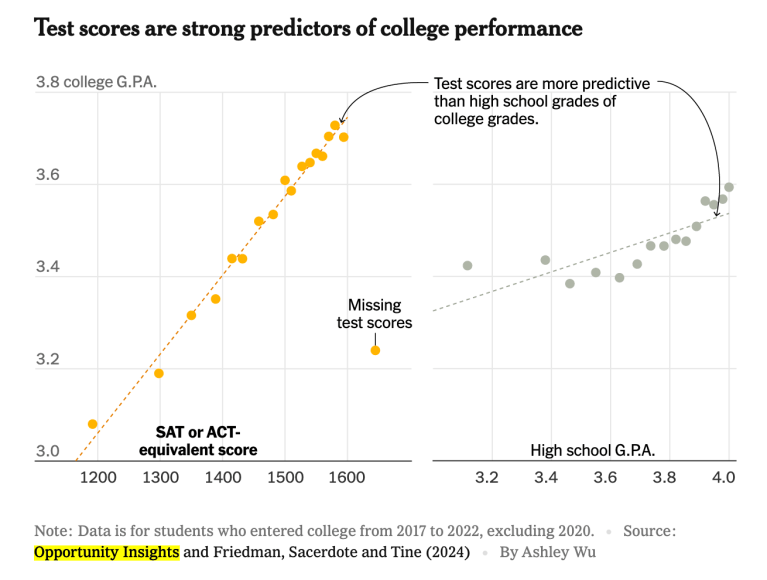

If your sole criterion for “success” is college GPA, you don’t need to take into account “advantage” or “disadvantage” educations, whether the sign of that be race, socioeconomic class, or reputation of the school. But there are other criteria for success, like the two below. Both are highly correlated with SAT (or ACT-equivalent) scores, but the outcomes haven’t been separated by socioeconomic class or race. It is possible that “overcoming adversity” could add to the predictability for getting into grad school or getting a good job above just using SAT scores. (Click to enlarge all graphs.)

It’s possible that if you had an expansive definition of “advantaged” education, which surely relies somewhat on socioeconomic class but also on other types of potential disadvantages (physical handicaps are one, but there are others), you could show that disadvantaged students with the same SAT score as advantaged students would nevertheless do better in life. Or, if you prize some kind of “experiential diversity” or “thought diversity” in colleges, then you might want to use criteria other than SAT scores or grades. In fact, that’s what many college-admissions essays are about: “Tell us about your life—what you’ve done, have you done anything unusual” etc. etc.

As far as rich white kids being able to do better because they can afford tutoring, music lessons and the like, Leonhardt says this with regard to the inequities that do exist among racial admissions:

The [SAT-like] tests are not entirely objective, of course. Well-off students can pay for test prep classes and can pay to take the tests multiple times. Yet the evidence suggests that these advantages cause a very small part of the [racial] gaps.

It’s a long article, but the point is this: SATs predict a lot about success, but there are still huge inequities among races in how they do, though that’s more a problem for elite schools than non-elite ones. If we’re concerned about more than just merit, but in things like thought diversity, experiential diversity, and (in my view) educational reparations, then what can we do?

First, here are the data on different ethnic groups in America, and how they think standardized tests should be counted in college admissions. It’s not that different among groups:

What is the solution to get students who will succeed while maintaining a decent racial balance?

We can use a “mixed strategy”:

But the data suggests that testing critics have drawn the wrong battle lines. If test scores are used as one factor among others — and if colleges give applicants credit for having overcome adversity — the SAT and ACT can help create diverse classes of highly talented students.

This has apparently worked at MIT, which dropped the test requirement for a couple of years and then reinstated it. The reinstatement brought improvement:

M.I.T. has become a case study in how to require standardized tests while prioritizing diversity, according to professors elsewhere who wish their own schools would follow its lead. During the pandemic, M.I.T. suspended its test requirement for two years. But after officials there studied the previous 15 years of admissions records, they found that students who had been accepted despite lower test scores were more likely to struggle or drop out.

Schmill, the admissions dean, emphasizes that the scores are not the main factor that the college now uses. Still, he and his colleagues find the scores useful in identifying promising applicants who come from less advantaged high schools and have scores high enough to suggest they would succeed at M.I.T.

Without test scores, Schmill explained, admissions officers were left with two unappealing options. They would have to guess which students were likely to do well at M.I.T. — and almost certainly guess wrong sometimes, rejecting qualified applicants while admitting weaker ones. Or M.I.T. would need to reject more students from less advantaged high schools and admit more from the private schools and advantaged public schools that have a strong record of producing well-qualified students.

“Once we brought the test requirement back, we admitted the most diverse class that we ever had in our history,” Schmill told me. “Having test scores was helpful.” In M.I.T.’s current first-year class, 15 percent of students are Black, 16 percent are Hispanic, 38 percent are white, and 40 percent are Asian American. About 20 percent receive Pell Grants, the federal program for lower-income students. That share is higher than at many other elite schools.

“When you don’t have test scores, the students who suffer most are those with high grades at relatively unknown high schools, the kind that rarely send kids to the Ivy League,” Deming, a Harvard economist, said. “The SAT is their lifeline.”

Leonhardt ends his piece with the quote at the top, followed by this:

Conservatives do it [ignore the data] on many issues, including the dangers of climate change, the effectiveness of Covid vaccines and the safety of abortion pills. But liberals sometimes try to wish away inconvenient facts, too. In recent years, Americans on the left have been reluctant to acknowledge that extended Covid school closures were a mistake, that policing can reduce crime and that drug legalization can damage public health.

There is a common thread to these examples. Intuitively, the progressive position sounds as if it should reduce inequities. But data has suggested that some of these policies may do the opposite, harming vulnerable people.

In the case of standardized tests, those people are the lower-income, Black and Hispanic students who would have done well on the ACT or SAT but who never took the test because they didn’t have to. Many colleges have effectively tried to protect these students from standardized tests. In the process, the colleges denied some of them an opportunity to change their lives — and change society — for the better.

If there’s any lesson in this, it’s that the “progressives” have been misguided in their call for dropping standardized tests. Doing so causes confusion and also leaves out many worthy students who have no other way of being identified. Standardized tests like the SATs should be required for all students, particularly in “elite” colleges, as a useful form of predicting who will do well and who won’t. But there are other criteria that should be considered, too. Readers are welcome to answer this question:

If you want a pure meritocratic admissions process, one that ensures that students get good grades in college, that can be done by relying almost entirely on SAT scores and not GPAs. But perhaps you’d prefer some criteria beyond those necessary to judge “probablility of success”. If so, what would you look for? (Remember, the Supreme Court has rule that race itself cannot be a criterion for admission.