Athayde Tonhasca Júnior has returned with a text-and-photo lesson in biology—in this case, strawberries. His narrative is indented and you can click on the photos to enlarge them.

Red Treasures

In the treasure trove of the garden’s heart,

strawberries play the sweetest part.

In their red, a work of art,

in their taste, a love to impart (anon.).The Dutch painter Hiëronymus Bosch (c. 1450–1516), the master of nightmarish landscapes and odd creatures, apparently had a thing for strawberries: the fruit is depicted thrice in his famed The Garden of Earthly Delights. The painting’s symbolism and the role of strawberries have been debated for a long time. The plant may be an allegory of sin and temptation, as it grows by creeping low on the ground, just like the Garden of Eden’s serpent. Strawberries were seen by some overimaginative medieval commentators as sensuous, erotic or virginal: Shakespeare’s Desdemona sported a handkerchief decorated with strawberries, a representation of fidelity. Others saw the fruit under a pious perspective, representing drops of Christ’s blood, while the plant’s tripartite leaves symbolised the Trinity. This religious angle explains the abundance of manuscripts, carvings, paintings and heraldic symbols decorated with strawberry fruits, leaves and flowers.

Detail of The Garden of Earthly Delights © Museo del rado, Wikimedia Commons.

Strawberries have a rich history of cultural symbolism in Medieval Europe, but they are scarce in culinary references. The main reason for that was the organoleptic shortcomings of the species available then, namely the woodland (Fragaria vesca), musk (F. moschata) and green (F. viridis) strawberries. These wild strawberries can be tasty, but also tangy, acidic, bitter, small, easily bruised and damaged by insects and diseases. So they were not on people’s lists of most desired fruits. All that changed in the 1700s, when European horticulturalists crossed two imports from the Americas, the Chilean (F. chiloensis) and Virginia (F. virginiana) strawberries. The resulting hybrid, Fragaria x ananassa, is the garden strawberry known to us today, and the source of all modern varieties cultivated around the world.

The garden strawberry has an agreeable balance between sweetness and acidity, and a complex blend of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) gives the fruit its distinct aroma and flavour. Other appealing traits such a hardiness, uniform shape and large size helped make the garden strawberry one of the most popular fruits in the world, and not only as a table staple: natural or synthetic strawberry extracts made their way into hundreds of products, from ice cream to cakes, jam, jelly, hard sweets, alcoholic beverages, non-alcoholic beverages, chewing gum, pharmaceuticals and cosmetics. The demand for fresh and frozen strawberries has been growing steadily for many years, and is not abating: strawberries are grown commercially in 76 countries, generating significant income for local economies. So, naturally, strawberry pollination has enormous importance. However, some of the plant’s morphological aspects renders this process less than straightforward.

Strawberries and cream feature at the Wimbledon Tournament since its debut in 1877. Each year more than 30 tons of strawberries are consumed in a fortnight © Paige orenze, Wikimedia Commons.

Strawberries, just like raspberries and blackberries, are aggregate fruits – or etaerios, if you want to be fancy – meaning that the succulent part we eat (the receptacle) develops from several ovaries fused together. In other words, each strawberry consists of one plump receptacle; the yellowish pips embedded on the strawberry’s surface, which are often assumed to be seeds, are in fact the fruits. Each one is an achene, a type of single-seeded, dry fruit. So, a strawberry is not a berry at all: berries are simple fruits, that is, they derive from one ovary that produces a single fleshy bit. A tomato is a berry, and so is a banana. Botany is complicated.

A close-up view of a strawberry’s achenes © rich caulton, Wikimedia Commons:

Strawberry flowers have male and female structures – they are hermaphroditic – and most varieties can self-pollinate: wind, rain and gravity take care of that. It may sound like the plant has its reproduction requirements sorted out, but that’s not so. The stigmas (the parts that receive the pollen) are usually ready before the anthers (the parts that produce the pollen), so that a plant may need to cross-pollinate with neighbours. But that’s the least of its difficulties.

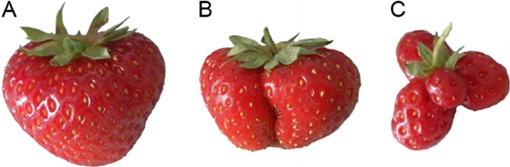

A large strawberry fruit holds about 200 achenes, and each one of them contains an ovule. Most of them must be fertilised so that the tissue around the achenes develops fully to form the enlarged receptacle. Unfertilized ovules do not stimulate tissue growth, and if there are too many of them, the result is a misshapen strawberry. These malformed fruits are perfectly healthy and edible but have little commercial value.

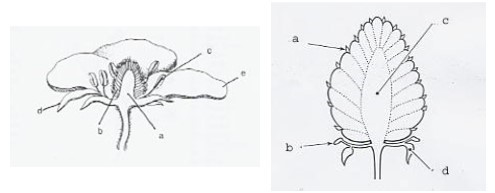

Left: Main parts of the strawberry flower – a: receptacle; b: pistils; c: anther; d: sepal; e: petal. Right: Structural features of the fruit – a: achene; b: stamen; c: receptacle; d: sepal © Poling, 2012.

The large number of ovules requiring pollination is a challenge because wind, rain and gravity take care of 60 to 70% of them. The rest must be done by bees and other insects. So, a fully formed, marketable strawberry is the result of autogamy (self-pollination) and allogamy (cross-fertilization) where insects are the vectors. But insects do much more to a strawberry than just pollinate it.

A: Fully formed fruit. B, C: Malformed fruits resulting from poor pollination © Klatt et al., 2014.

Fertilised achenes produce auxins and gibberellic acids, plant hormones that stimulate growth and thus are responsible for increasing the fruit’s size and weight. But these hormones also slow down the process of tissue-softening, so the fruit is firm for longer. This delay increases shelf life, which is hugely important for strawberry commercialisation: more than 90% of the harvested fruits can become non-marketable after four days in storage because of excessive softness, which induces fungal infections and mechanical injuries (Klatt et al., 2014). About one-third of the global food produced for human consumption is wasted during handling, transport and storage (Gustavsson et al., 2011); by increasing the number of pollinated achenes, insects do their bit to reduce these losses.

A strawberry flower. Most of the pistils (grouped inside the circle) must be pollinated for a fully formed fruit © Wikimedia Commons:

There’s a considerable range of strawberry varieties grown under different agronomic practices, but overall, Gudowska et al. (2024) estimated that insects contribute to 25% of fruit weight, a benefit worth US$ 5.4 billion per year to the producers worldwide. This ecological service is often attributed to the European honey bee (Apis mellifera), but bumble bees, honey bee-mimicking drone flies (Eristalis spp.) and the green bottle fly (Lucilia sericata) are among the most efficient pollinators of strawberry. And some other visitors could be even better: in Canada, MacInnis & Forrest (2019) observed that flower visitation by Augochlorella spp. and Lasioglossum spp. sweat bees resulted in fruits ~40% heavier when compared to flowers visited by honey bees. Here, insect sizes made all the difference: the relatively small sweat bees (5–7 mm in length) forage for pollen and nectar without disturbing the anthers, whereas the larger honey bees (>10 mm), which are after nectar only, often bend the anthers towards the stigmas. By doing so, honey bees may accidentally promote self-pollination, which may reduce fruit set when compared to cross pollination.

A Lasioglossum sp. sweat bee © David Cappaert, Invasive.org:

The garden strawberry is a case study of the role of pollination for crop production. It’s not an indispensable service in most cases, but without it, yields, produce quality and revenue can suffer significantly. A bowl of strawberries would not be as tasty, visually appealing or affordable without insects.

The Sweety Viper is most thankful to insect pollinators © Sin Amigos, Wikimedia Commons:

FROM JERRY: Athayde forgot to mention the very quintessence of strawberry products: Tiptree “Little Scarlet” Strawberry Conserve: the best jam in the world, made with tiny wild strawberries grown on the Wiklin & Sons property. It was a favorite of James Bond. It’s not always available in the U.S., but you can buy it now on Amazon for only $9.69 per jar. Take my word for it: you won’t find a better jam (or”preserves” as the Brits call it).

“Breakfast was Bond’s favourite meal of the day. When he was stationed in London it was always the same. It consisted of very strong coffee, from De Bry in New Oxford Street, brewed in an American Chemex, of which he drank two large cups, black and without sugar. The single egg, in the dark blue egg cup with a gold ring round the top, was boiled for three and a third minutes.

It was a very fresh, speckled brown egg from French Marans hens owned by some friend of May in the country. (Bond disliked white eggs and, faddish as he was in many small things, it amused him to maintain that there was such a thing as the perfect boiled egg.) Then there were two thick slices of wholewheat toast, a large pat of deep yellow Jersey butter and three squat glass jars containing Tiptree `Little Scarlet’ strawberry jam; Cooper’s Vintage Oxford marmalade and Norwegian Heather Honey from Fortnum’s. The coffee pot and the silver on the tray were Queen Anne, and the china was Minton, of the same dark blue and gold and white as the egg-cup.”

Ian Fleming, Chapter 11, From Russia, With Love (1957)

I must admit that wild strawberries put the commercial waterlogged giant offerings to shame: they are full of flavour and well worth the considerable effort of picking. The edges of our woods are loaded with them.

My taste buds are excited!

Can confirm the Tiptree – bought it on PCC(E)’s recommendations. Quite unlike grocery store stuff.

Interesting stuff about strawberries. Little Scarlet is good!

I always enjoy reading these brief treatises. Thank you very much.

Super interesting. We had some tiny wild strawberries on our property on Orcas Island. The strawberries themselves were about a centimeter in diameter and were absolutely delicious, both to us and to the deer.

Why is it that the giant plum-sized strawberries we occasionally receive (or give) as gifts—often with chocolate on them—are so tasteless? They look beautiful, their huge size generates oohs and aahs, but they have almost no taste, except for a bit of sourness. Why? Do they absorb so much water that the water overwhelms whatever flavor chemicals they have inside? Inquiring minds need to know.

I would guess aging on the vine is key to flavor. As it is with tomatoes.

But just yesterday we had a birthday cake with huge strawberries, and I’d say they were excellent.

Yes! Haven’t we all been fooled by the flawless strawberry found in the grocery store? Such a disappointment! It’s a shame that the misshapen fruits are rendered “unmarketable” . I’ve pretty much quit buying fruit in the stores. The “ugly” specimens that come out of my Syrian neighbor’s yard (here in Tucson) have ruined me for store-bought produce. Even the stuff marked “organic” (do you think it really is?) is tasteless.

Another fascinatingly informative lesson in biology, Athayde. Thank you

Thank you for this. I live in a strawberry growing region but knew almost nothing about their biology.

As always, an interesting post! Thanks!

Another great post! I had looked up and learned that the commercial interspecies hybrid is also octoploid — having 8 sets of chromosomes. That may be the reason they are so big.

Fascinating, as always. Many thanks!

Athayde, I always love your very interesting posts! Do you mind my asking where you’re originally from? I’m very interested in languages, and have never heard your name before. I’m assuming Spanish or Latin American? (I have a Salvadoran sister-in-law who lives with my brother in Antigua, Guatemala🌞

I remember my (botanist, amateur, but very good – “Valhalla” class in the BSBI) father pointing out an “original” strawberry one day while walking across the “Juniper Pot” escarpment of Ingleborough. “That,” pointing at a tiny blob of a few mm diameter, “is what your supermarket strawberries descend from”. Increased 1000+-fold (10 times on each axis) – that is breeding.

Oddly, the 60m drop into a gaping chasm of “Juniper Pot” hadn’t appealed to him, even after I’d pointed out the important anchors. It is a … thought-provoking entrance. It’s only a minute or so of commitment to the rope. And the bolts.

Wonderful post! Our wild strawberries are flowering now. I will be watching for the pollinators.

Brilliant stuff, as always. Whenever I see one of your posts I sigh, because I know any other tasks I need to do will suffer while I read your post!