This article from Tablet describes “How the Gaza Ministry of Health Fakes Casualty Numbers“, and while I have a few quibbles with it (or rather, alternative but not-so-plausible interpretations), the author’s take seems pretty much on the mark. Abraham Wyner simply gives the daily and cumulative death-toll accounts of Palestinians taken from the Hamas-run Gazan Health Ministry between October 26 and November 10 of last year, and subjects them to graphical and statistical analyses.

The conclusion is that somebody is making these figures up. They aren’t necessarily inaccurate, but the article makes a strong case that there’s some serious fiddling going on. And the fiddling seems to be, of course, in the direction that Hamas wants.

I’ve put the figures Wyner uses below the fold of this post so you can see them (or analyze them) for yourself. As the author notes, “The data used in the article can be found here, with thanks to Salo Aizenberg who helped check and correct these numbers.”

Click on the link to read.

The data are the daily totals of “women”, “children”, and “men” (men are “implied”, which probably means that Wyner got “men” by subtracting children and women from the “daily totals”). Also given are the cumulative totals in the third column and the daily totals in the last column.

When you look at the data or the analysis, remember three things:

- “Children” are defined by Hamas as “people under 18 years old”, which of course could include male terrorists

- “Men” include terrorists as well as any civilians killed, and there is no separation, so estimates of terrorists death tolls vary between Hamas and the IDF, with the latter estimating that up to half of deaths of men could be terrorists

- A personal note: I find it ironic that Hamas can count the deaths to a person but also say they don’t have any idea of how many hostages they have, or how many are alive.

On to the statistics. I’ll put Wyner’s main findings in bold (my wording), and his own text is indented, while mine is flush left.

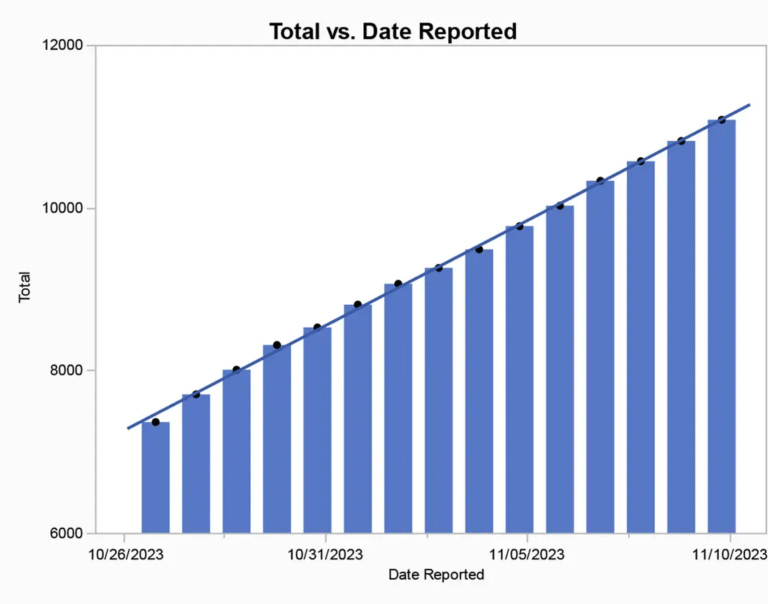

The cumulative totals are too regular. If you look at the cumulate death totals over the period, they seem to go up at a very even and smooth rate, as if the daily totals were confected to create that rate. Here’s the graph:

Cumulative totals will always look smoother than the daily totals, so this may be a bit deceptive to the eye. However, Wyner also deals with the daily totals, which are simply too similar to each other to imply any kind of irregular daily death toll, which one would expect in a war like this. As he says of the above:

This regularity is almost surely not real. One would expect quite a bit of variation day to day. In fact, the daily reported casualty count over this period averages 270 plus or minus about 15%. This is strikingly little variation. There should be days with twice the average or more and others with half or less. Perhaps what is happening is the Gaza ministry is releasing fake daily numbers that vary too little because they do not have a clear understanding of the behavior of naturally occurring numbers. Unfortunately, verified control data is not available to formally test this conclusion, but the details of the daily counts render the numbers suspicious.

The figures for “children” and “women” should be correlated on a daily basis, but aren’t. Here’s what Wyner says before he shows the lack of correlation:

Similarly, we should see variation in the number of child casualties that tracks the variation in the number of women. This is because the daily variation in death counts is caused by the variation in the number of strikes on residential buildings and tunnels which should result in considerable variability in the totals but less variation in the percentage of deaths across groups. This is a basic statistical fact about chance variability. Consequently, on the days with many women casualties there should be large numbers of children casualties, and on the days when just a few women are reported to have been killed, just a few children should be reported. This relationship can be measured and quantified by the R-square (R² ) statistic that measures how correlated the daily casualty count for women is with the daily casualty count for children. If the numbers were real, we would expect R² to be substantively larger than 0, tending closer to 1.0. But R² is .017 which is statistically and substantively not different from 0.

This lack of correlation is the second circumstantial piece of evidence suggesting the numbers are not real. But there is more. . .

This seems reasonable to me, although if a large number of “children” are really terrorists fighting the IDF and are not with women, this could weaken the correlation. But given Hamas’s repeated showing of small children in its propaganda, one would indeed expect a pretty strong correlation. In fact, the probability of getting this value of R² (actually, the proportion of the variation in daily women killed explained by the number of men killed) is a high 0.647, which means that if there was no association, you would get an R² this large almost 65% of the time. To be significant the probability should be less than 0.05: less than a 5% probability that the observation association would have happened by chance alone.

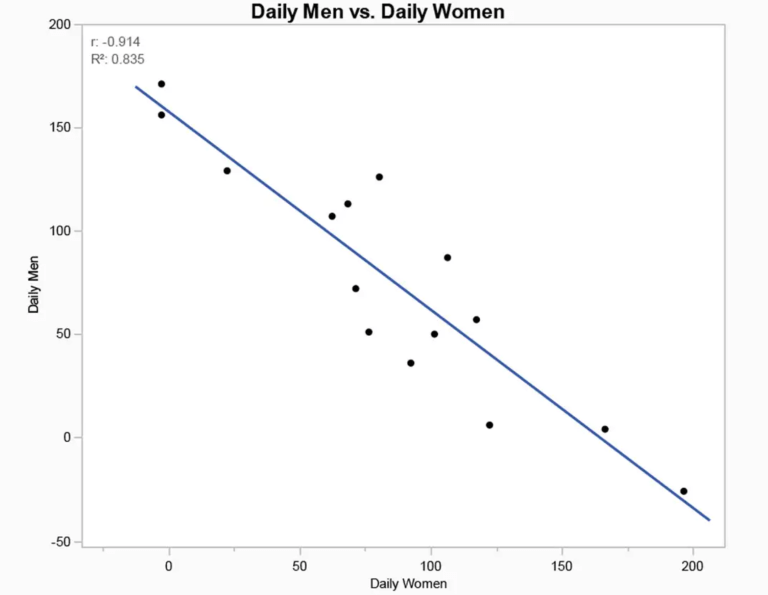

There is a strong negative correlation between the number of men killed and the number of women killed. The daily data plotted over time shows that this is a very strong relationship: the more women killed on a given day, the fewer men killed on that day. Below is the plot and what the author says about it.

The daily number of women casualties should be highly correlated with the number of non-women and non-children (i.e., men) reported. Again, this is expected because of the nature of battle. The ebbs and flows of the bombings and attacks by Israel should cause the daily count to move together. But that is not what the data show. Not only is there not a positive correlation, there is a strong negative correlation, which makes no sense at all and establishes the third piece of evidence that the numbers are not real.

The correlation between the daily men and daily women death count is absurdly strong and negative (p-value < .0001).

The figure is indeed strongly negative, and isn’t due to just one or two outliers. The R value itself (the Pearson correlation coefficient) is a huge -0.914 and what we would call “highly significant”, with a probability that a correlation this large have occurred by chance being less than one in ten thousand. It’s clearly a meaningful relationship.

Is there a genuine explanation for this, one suggesting that the numbers are not made up? I could think of only one: on some days men are being targeted, as in military operations, while on other days both sexes are targeted, as if Israel is bombing both sexes willy-nilly. But that doesn’t make sense, either—not unless the men and women are in separate locations (when a lot of women are killed on a given day, almost no men are killed). Look at the data below the fold, for example: on October 30 no women were reported killed but 171 men were killed. That could happen only if on that day Israel was targeting only men, which would mean they were going after terrorists. But that’s not Hamas’s interpretation, of course.

Conversely, on the next day 6 men were reported killed and 125 women. Was the IDF targeting women? None of this makes sense.

There are other anomalies in the data. Here’s one:

. . . . the death count reported on Oct. 29 contradicts the numbers reported on the 28th, insofar as they imply that 26 men came back to life. This can happen because of misattribution or just reporting error.

Indeed, as on October 29 there were 2619 deaths in the cumulative total of men (implied), but on the day before, October 28, there were more: 2645! Take a look at the chart below the fold.

One more anomaly:

There are a few other days where the numbers of men are reported to be near 0. If these were just reporting errors, then on those days where the death count for men appears to be in error, the women’s count should be typical, at least on average. But it turns out that on the three days when the men’s count is near zero, suggesting an error, the women’s count is high. In fact, the three highest daily women casualty count occurs on those three days.

Here’s how the author explains the data:

Taken together, what does this all imply? While the evidence is not dispositive, it is highly suggestive that a process unconnected or loosely connected to reality was used to report the numbers. Most likely, the Hamas ministry settled on a daily total arbitrarily. We know this because the daily totals increase too consistently to be real. Then they assigned about 70% of the total to be women and children, splitting that amount randomly from day to day. Then they in-filled the number of men as set by the predetermined total. This explains all the data observed.

After deciding that we can’t get any numbers other than these, and adding that we can’t differentiate civilians from soldiers, or accidental deaths caused by misfired Gazan rockets, Wyner leave us with this conclusion:

The truth can’t yet be known and probably never will be. The total civilian casualty count is likely to be extremely overstated. Israel estimates that at least 12,000 fighters have been killed. If that number proves to be even reasonably accurate, then the ratio of noncombatant casualties to combatants is remarkably low: at most 1.4 to 1 and perhaps as low as 1 to 1. By historical standards of urban warfare, where combatants are embedded above and below into civilian population centers, this is a remarkable and successful effort to prevent unnecessary loss of life while fighting an implacable enemy that protects itself with civilians.

People tend to forget this ratio, which is stunningly low for fighting a war in close quarters against an enemy that uses human shields. (The link to “historical standards” goes to PBS and an AP report, so it isn’t exactly from Hamas). Besides showing us that we can’t trust Hamas’s figures, which nevertheless are touted in all the media, it also shows that there is no indication that the Israelis are trying to wipe out the Palestinian people; that is, there is no genocide going on.

But it would be nice, if newer figures were available, to see if these anomalies are still there. This article is from March 6, so it’s pretty new.

Click “continue reading” to see the data

Continue reading “Hamas plays fast and loose with the casualty numbers from Gaza”