Remember “Woke Kindergarten”, a lesson plan for teachers to use in instructing propagandizing students in Hayward, California (see posts here and here)? The program was designed by an extreme “progressive” named Akiea “Ki” Gross, who was given $250,000 in taxpayer money by the school. And, lo and behold, performance in English and math actually dropped after the wokeness was sprayed on the students. (To see how completely bonkers this program is, go here or to the program’s website here.) All power to the little people! Sadly, the program appears to be designed for black students and the students are 80% Hispanic.

After an article was published in the San Francisco Chronicle describing the program, there was a huge backlash from people who, properly, thought it was bonkers. So what did the school district do? Did they drop the program? There’s no indication of that. Instead, they did what defies common sense: they put one of the teachers who criticized the program in the article on leave (with pay) for unknown violations. They are actually defending Woke Kindergarten when they should be defunding it. I suspect, however, that we’ll see no more of the program. It’s simply too stupid, woke, and embarrassing.

At any rate, the Chronicle has a new article (click headline below, or find it archived here), discussing the firing and giving the school’s defense.

First, though, this is how the teacher critic was quoted in the first Chronicle article:

Tiger Craven-Neeley said he supports discussing racism in the classroom, but found the Woke Kindergarten training confusing and rigid. He said he was told a primary objective was to “disrupt whiteness” in the school — and that the sessions were “not a place to express white guilt.” He said he questioned a trainer who used the phrasing “so-called United States,” as well as lessons available on the organization’s web site offering “Lil’ Comrade Convos,” or positing a world without police, money or landlords.

Craven-Neeley, who is white and a self-described “gay moderate,” said he wasn’t trying to be difficult when he asked for clarification about disrupting whiteness. “What does that mean?” he said, adding that such questions got him at least temporarily banned from future training sessions. “I just want to know, what does that mean for a third-grade classroom?”

And from the new piece, his punishment for such heresy:

The East Bay teacher who publicly questioned spending $250,000 on an anti-racist teaching training program was placed on administrative leave Thursday, days after he shared his concerns over Woke Kindergarten in the Chronicle.

Hayward Unified School District teacher Tiger Craven-Neeley said district officials summoned him to a video conference Thursday afternoon and instructed him to turn in his keys and laptop and not return to his classroom at Glassbrook Elementary until further notice.

They did not give any specifics as to why he was placed on paid leave, other than to say it was over “allegations of unprofessional conduct,” Craven-Neeley said.

District officials declined to comment on his status or any allegations, saying it was a personnel matter.

A defense of Woke Kindergarten from the original article:

District officials defended the program this past week, saying that Woke Kindergarten did what it was hired to do. The district pointed to improvements in attendance and suspension rates, and that the school was no longer on the state watch list, only to learn from the Chronicle that the school was not only still on the list but also had dropped to a lower level.

Defenses in the second article. Yep, they refuse to say that adopting it was a bad move:

District officials declined to comment on their social media posts, given Gross was paid using taxpayer-funded federal dollars.

“We cannot comment on her personal political or social views,” Bazeley said.Some teachers have defended the Woke Kindergarten program, saying that after years of low test scores and academic intervention, they believed in a fresh approach. The training was selected by the school community, with parents and teachers involved in the decision.

“We need to try something else,” said Christina Aguilera, a bilingual kindergarten teacher. “If we just focus on academics, it’s not working. There is no one magic pill that will raise test scores.

“I’m really proud of Glassbrook to have the guts to say this is what our students need,” Aguilera said. “We didn’t just do what everybody expected us to do, and I’m really proud of that.”

Sixth-grade teacher Michele Mason said the Woke Kindergarten training sessions “have been a positive experience” for most of the staff, humanizing the students’ experiences and giving them a voice in their own education.

These are clearly teachers who want to keep their jobs. Finally, a bit about how Craven-Neeley was treated by his colleagues:

The Wednesday staff meeting, however, was tense, Craven-Neeley said, as he tried to explain that before going to the Chronicle, he approached school and district staff as well as the school board to raise questions about the program and the expense, with no response.

“There was so much anger toward me,” he said. “I was explaining my point of view. They were talking over me.”

. . . . Craven-Neeley said the meeting grew tense about an hour in, when another teacher stood up, pointed a finger in his face and said, “ ‘You are a danger to the school or the community,’ and then she walked out of the room.”

Not long after, a district administrator asked him to leave the meeting.

“I was shocked. This is my school. I didn’t do anything inappropriate,” he said. “I left. I was very shaky.”

Another Glassbrook teacher, who requested anonymity for fear of repercussions at the school, confirmed that a staff member put a hand in Craven-Neeley’s face and called him a disgrace and a threat to the school.

Craven-Neeley then had a video meeting with school officials and was told he’d be placed on paid leave pending an “investigation”. The university also “denied the district’s actions were related to Craven-Neeley’s participation in the story or his complaints about the program. The district spokesperson added, ‘We would not put any employee on leave as any sort of retaliation or squelch anyone’s free speech rights,” [Michael Bazeley] said’.”

Well that sounds like a flat-out lie to me. What Craven-Neeley said to the Chronicle was indeed free speech, and there’s no other indication of anything else for which he’d be punished. All I can say is that it looks as if Woke Kindergarten affected the teachers (if not the students). They’re all censorious and defensive!

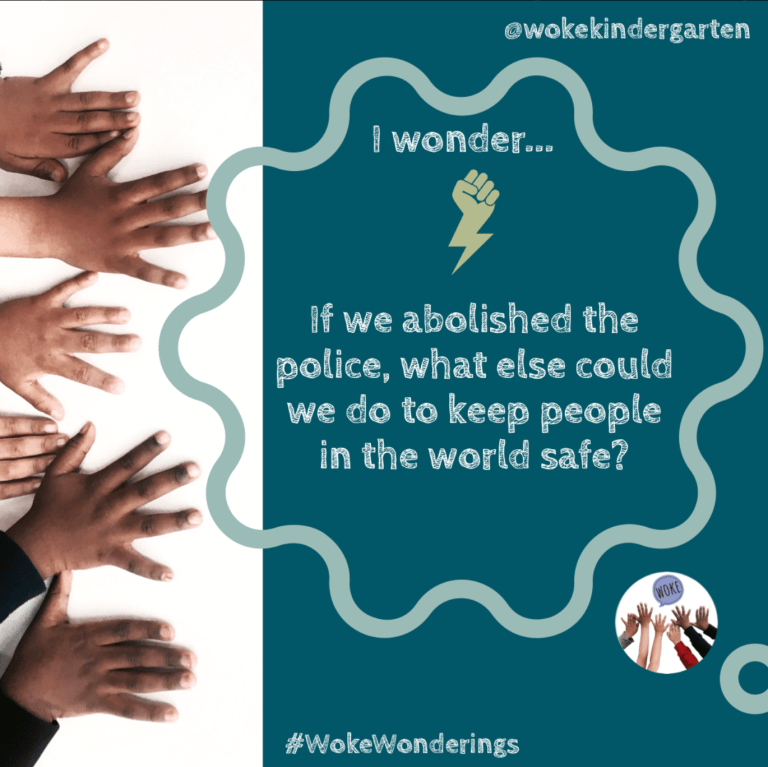

Remember the “woke wonderings” that were part of the program? Here’s one:

The answer, of course, is “not much!”