The virus that has long infected New Zealand—the argument that indigenous “ways of knowing” should be taught alongside science in the science classroom—has now spread to America, with the help of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) and its flagship journal, Science, often regarded as one of the world’s most prestigious venues.

But Science screwed up this time, publishing a tendentious, confusing, and virtually fact-free three-page “policy forum” argument that, yes, indigenous science should be taught alongside science in the classroom. This kind of defense is typical of what’s going on in New Zealand, where, ever since the “Listener Letter” (original version here) was published in 2021, there’s been an acrimonious debate about whether local ways of knowing—the Mātauranga Māori (henceforth MM) of the indigenous Māori people—should be taught as science in the science classroom.

I’ve written dozens of posts on this controversy and am pretty well acquainted with MM, so I can’t be accused of ignorance of the indigenous “ways of knowing”—a point the authors, both from New Zealand, frequently level at their opponents.

In general, my view is yes, there is indigenous knowledge and truth in the “ways of knowing” of indigenous people, whether they be from New Zealand, Australia, or North America. But the “way of knowing” of these groups is not at all the same thing as modern science, with its toolkit of ways to find truth. Indigenous “ways of knowing” incorporate much more than empirical fact, including (in MM and other such systems) morality, religion, spirituality, vitalism, and tips about how to live and get along with other groups in your “tribe.” Thus, while some empirical facts from indigenous people can be taught in science class, there aren’t many that would fit in, since they’re usually practical facts about gathering food or how to make implements. This is in contrast with modern science, which is more than just a collection of facts but a toolkit of ways to find those facts (see my book Faith Versus Fact). Thus, while one can incorporate indigenous “facts” into science class, they should occupy at best a few percent of the content. How much “indigenous physics” can be taught in a class on modern physics? To teach indigenous “ways of knowing” as just as valid as—or “equivalent” to—as modern science, something the authors recommend, will be deeply confusing to students and would hurt science education. Indigenous ways of knowing are not equivalent to science, and are inferior to modern science in the business of finding truth. To say that is to commit heresy.

In the end, this article appears to me to be a DEI-ish contribution: something published to advance “the authority of the sacred victim” by arguing that indigenous knowledge and ways to attain it is just as good as modern (sometimes called “Western” ) science, and that teaching it will empower the oppressed. Here’s one line from the paper supporting my hypothesis:

In addition to a suite of known benefits to Indigenous students, we see the potential for all students to benefit from exposure to Indigenous knowledge, alongside a science curriculum, as a way of fostering sustainability and environmental integrity.

In other words, the argument here is really meant to buttress the self image of indigenous people, not to buttress science. You can see this because there are hardly any examples given to support their thesis. Instead, there is a lot of palaver and evidence-free argument, as well as both tedious and tendentious writing.

The publication of this paper is somewhat of a travesty, for it shows that the AAAS is becoming as woke as New Zealand, where the claim that you should NOT teach MM in the science classroom can get you fired! If this kind of stuff continues, the authoritarians will eventually shut down anybody who makes counterarguments, as is happening in New Zealand, where counterspeech against the “scientific” nature of MM is demonized and punishable. Did the AAAS even get critical reviewers for this piece?

Click headline to read:

Let’s begin by defining three terms, as I define them in Faith versus Fact, taking them from the OED, my authoritative source

fact: “something that has really occurred or is actually the case; something certainly known to be of this character; hence, a particular truth known by actual observation or authentic testimony, as opposed to what is merely inferred. . .”

truth: “conformity with fact; agreement with reality, accuracy, correctness, verity (of statement or thought)”

knowledge: “The apprehension of fact or truth with the mind; clear and certain perception of fact or truth; the state or condition of knowing fact or truth.” I interpret this to mean “the public acceptance of facts”, so that “knowledge” becomes an apprehension, as Steve Gould argued, would be held by any person who is not perverse.

way of knowing: A system or group of procedures used to produce knowledge. (This is my definition since it’s not in the OED.)

My claim is that indigenous people can ascertain facts and truths, but whether these constitute “knowledge” to which all assent requires the participation of modern science. And I also claim that indigenous “ways of knowing” are not the best ways to find truth, as they’re usually polluted with things like spirituality, myth, and tradition. In fact, I’d say that science construed broadly (i.e. using the toolkit of science) is by far the best way to find truth, and that indigenous ways of knowing are inferior to modern science.

That conclusion is anethema to authors Black and Tylianakis, as they insist that indigenous ways of knowing are not inferior to modern science (that’s why they should be taught alongside modern science), and are just as valid in producing knowledge. Black and Tylianakis are wrong, and you can see this by realizing that indigenous knowledge has, at best, progressed only a small bit in the last 200 years or so, while science has increased our knowledge of the universe immeasurably in just a century. But I emphasize that indigenous “ways of knowing” are not useless, for they help us understand the thought of different cultures. They should be taught in sociology and anthropology class, but not in science class.

Okay, on to a few claims of the paper, which I’ll put under my own bolded headings. Quotes from the paper are indented:

Indigenous knowledge is of considerable value in enhancing and expanding science and should be taught as alongside science in the science class.

We argue that Indigenous knowledge can complement and enhance science teachings, benefitting students and society in a time of considerable global challenges. We do not argue that Indigenous knowledge should usurp the role of, or be called, science. But to step from “not science” to “therefore not as (or at all) valuable and worthy of learning” is a non sequitur, based on personal values and not a scientifically defensible position.

The problem throughout the paper is twofold. First, nobody ever said that indigenous knowledge is not valuable. Some of it is (many drugs like quinine came from indigenous knowledge), but I add that testing whether quinine really works required modern science: controlled, double-blind studies. Second, the authors give only one example I can see of how indigenous knowledge is supposed to enhance modern scientific knowledge—and that example is misguided. (See below.)

Indigenous knowledge is of equal value to modern scientific knowledge, but the former is often presented in “simplistic caricatures”. Bolding below is mine:

One attempt to provide policy protections and opportunities for Indigenous knowledge is the Aotearoa–New Zealand government’s decision to ensure that Indigenous knowledge (Mātauranga Māori) has equal value with other bodies of knowledge in the school curriculum, after lengthy advocacy from Māori educators to honor the Treaty of Waitangi, Aotearoa– New Zealand’s founding document.

. . . We suggest that many of the arguments used to “defend” science by presenting Indigenous knowledge as inferior are themselves rooted in logical fallacies. We also argue that the treatment of all Indigenous knowledge as myth is at odds with the literature, which emphasizes a continuum from empirical and science-like aspects of Indigenous knowledge to philosophical and metaphysical ones

. . . Moreover, we argue that there is a cost to rejecting Indigenous knowledge, in that framing it with simplistic caricatures misses the potential for complementarity between science and Indigenous knowledge.

This of course depends on what you mean by “equal value.” If we’re arguing about scientific value, which, given the article’s title, seems to be what the authors mean, I’d say that MM is less valuable by far than modern science, as evidenced by its scanty record of advancing knowledge. But as a way of understanding cultures, yes, one could argue that MM is comparable in sociological value to modern science (i.e., in understanding a culture’s “way of knowing.”)

I don’t know anyone who thinks that all indigenous knowledge is myth. If that were true, indigenous people wouldn’t be have been able to live. But it is inferior to modern science is finding knowledge.

And as for “simplistic caricatures”, well, I have tried hard to present MM as it really is, though of course I’m not Māori. But nobody who studies MM can doubt that it is not the same thing as modern science, for MM is imbued with religion and spirituality, conveyed by traditions and myths, and full of morality, ideology, and advice about how to live. Those are most definitely not things to be taught in science class.

A lot of the verbiage of this paper is confusing, for much is drawn from postmodernism. Look at this, for example:

Similarly, we argue that teaching Indigenous knowledge alongside science should not seek to usurp science (in the way that, for example, creationism seeks to undermine evolutionary theory because they are incompatible with one another), but rather it “provokes science, and can act as a mirror for science to see itself more clearly, reflected in a philosophically different form of knowledge” .

What does it mean to “provoke science” or “act as a mirror for science to see itself more clearly”? Could we have an example, please? Like many of the papers defending MM from criticism, there is a glaring dearth of examples to clarify the authors’ claims.

Indigenous knowledge can contribute to conservation. This is the oft-made claim that indigenous peoples were assiduous stewards of the land, careful to manage it so they could sustain ecosystems. This is debatable at best, and in the case of the Māori extremely debatable. Yes, it’s true that some factual knowledge of the environment can help modern conservationists preserve the land, but I would deny that indigenous “ways of knowing” sit alongside modern conservationism as ways 0f helping preserve the planet. A claim from the paper:

The timescales of knowledge generation are also complementary. For example, short-duration scientific research funding cycles can create institutional barriers to long-term data acquisition and study of large-scale (such as environmental) problems. By contrast, Indigenous knowledge can and has contributed empirically generated, intergenerational knowledge, making it an increasingly valuable tool in environmental management, particularly around rare but increasingly frequent natural events such as large-scale deadly bush fires that plague Australia and parts of North America. For at least 40,000 years, Indigenous Australians have been managing the landscape, leaving a deep human imprint, one that has been nearly erased from living memory. However, in parts of Australia, local authorities, scientists, and Indigenous communities are now coming together to revisit Indigenous fire management and reframing science through Indigenous knowledge to better understand these modern environmental dilemmas

Is it true that indigenous people managed the landscape better than modern conservationists? (I’ll freely admit that early European colonists didn’t manage the landscape at all, but rather clear-cut huge swaths of forest.) Here are a few counterexamples.

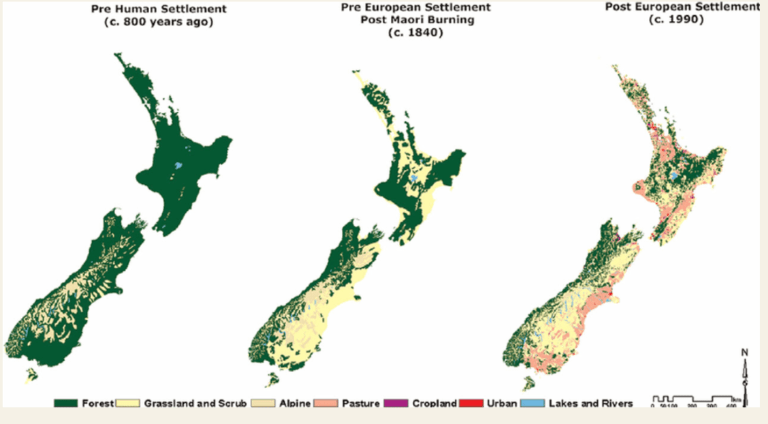

The fires set by indigenous people in North America and New Zealand (I don’t know about Australia) were not meant to conserve the land, but to produce clearings to hunt bison or simply to clear the forest. And in New Zealand the indigenous people clear-cut more forest than did the colonists; here’s something I wrote a while back:

I can’t help but add here that the idea that the Māori consider themselves part of the environment, stewarding it carefully as opposed to the “destroy it all” Europeans–isn’t correct. What we know is that between the arrival of Polynesians on the island (13th century) and the colonization by Europeans (18th century), the main method of Māori cultivation involved burning off the native forest. Māori burning was so extensive that it could be detected in Antarctic ice cores, and is estimated to have reduced the forest cover of the island from 80% to 15% (compare left with middle figures below). Europeans of course burned [additional] forest, and that you can see by comparing the middle figure to the right figure. They don’t like to talk about the Māori burnings in NZ, but researchers agree that a substantial part of the reduction in virgin forest cover was caused by the indigenous people. (They also, of course, drove the moas extinct by killing them for food.)

Here’s the result of forest removal by the and after European colonization (from Weeks et al. 2012)

I added that to put some perspective on the claim that Europeans were the people who really destroyed the forests of NZ while the Māori were taking good care of it. And, of course, NZ now has one of the world’s best conservation efforts—largely a product of Western science.

I no longer use the term “Western” science, for although modern science was developed in the West, it’s now the property of the entire world, and practiecd by people everywhere.

The Maori of course helped drive the nine species of native moas (large flightless birds) to extinction, killing them for food. Likewise, native people helped drive large native mammals to extinction in several places. Now the authors do raise the issue of the poor moas, but only to dismiss it:

Yet although Indigenous knowledge is also well known to be dynamic and continuously updated, critics do not afford it an equal right to correct itself. For example, “pity the moas were all eaten” is commonly used rhetoric to imply the failure of Māori knowledge around conservation of a giant endemic New Zealand bird in the 15th century. Yet this reasoning mistakenly conflates the validity of present-day Indigenous knowledge with 15th-century knowledge and decision-making.

If “do not kill moas” is now part of MM, I don’t know of it. But I jest (in part). The real implication here is that MM can revise itself in light of new facts. And that’s the case to some extent, for they’ve hit on new ways to catch seafood, for example. But “knowledge” based on spirituality and tradition is not subject to empirical revision. One example is the claim of some Māori authors (based on a mistranslation) that the Polynesians (their ancestors) discovered Antarctica in the seventh century A.D. (Part of the legend is that they used canoes made of human bones.) This is now uniformly refuted by all sentient anthropoids, who know that Antarctica was really discovered by the Russians in 1820. But the authors have never admitted they were wrong, and in fact persist in their claims (see my posts here, here, here, and here). And where are the revisions, in light of modern science, of the claims of some North American “first people” that their ancestors were always here and didn’t come over from Asia? Has anybody seen one admission of that?

Further, the Maori still cling to a very important component of their way of knowing: the vitalism or “life force” called mauri. As Nick Matzke has pointed out in a video, MM still largely rejects “methodological naturalism”, the view that natural laws are always at work, everywhere. In my analysis of Nick’s arguments (he doesn’t see MM as an equivalent to modern scientific “ways of knowing”), I said this:

In Māori culture, “Mauri” is defined this way:

life principle, life force, vital essence, special nature, a material symbol of a life principle, source of emotions – the essential quality and vitality of a being or entity.

And it has been invoked as something that was to be used in the chemistry curriculum for 14- and 15-year-old: particles and atoms were said to have their own “mauri”. To Nick (and to me) this is an unacceptable form of vitalism, given that science has found no evidence for vitalism or teleology in any aspect of science. Nick in fact wrote a letter to the New Zealand Herald highlighting this (see below). My own post on mauri and chemistry (and electrical engineering!) is here.

If MM is to be taught alongside science, a lot of its claims are going to have to be stripped away: yes, just those claims that conflict with modern science. In contrast, we don’t have to change what we teach as modern science in light of modern claims.

The knowledge produced through traditional science methods has resulted in many game-changing outcomes, such as the eradication of smallpox and the production of life-saving vaccines. However, it has also proven itself wrong (for example, phlogiston, aether, and phrenology) and produced catastrophic outcomes for humanity (such as the atomic bomb), while failing thus far to solve the most pressing challenges of our time (such as climate change). As scientists, we accept such scientific shortcomings on the basis that they are corrected as part of the scientific process, in which knowledge is updated as new information becomes available.

These are shortcomings not of science itself, but of scientists. But science itself also ensures that this knowledge is self-correcting. Where is the self-correction in MM that, say, will get the authors of the ridiculous Antarctica papers to admit that they were wrong? Or to get advocates of MM to admit that there is no mauri, no life force? Those corrections are part of the toolkit of modern science, but figure into traditional “ways of knowing” only insofar that a claimed observation about nature was later found to be wrong. There is no “toolkit” of indigenous knowledge that is agreed on by all observers: no double-blind testing, no wide use of hypothesis, no endemic doubt, use of predictions, and so on.

Diversity promotes innovation. If we’re talking about diversity of ideas here, I’m on board. But does diversity of “ways of knowing” advance science? Conceivably it could, by adducing new facts, but where are the examples? The authors give none:

Innovation draws from diversity

Innovation, like evolution, draws from diversity, so that diversity of knowledge sources and transfer among them are known to positively influence innovation (15). This value is exemplified by the move toward cross-disciplinarity, in which science can draw on inductive fields of research for hypothesis generation. Given this value of diversity, global challenges faced by humanity could benefit from inclusive science and maintenance of knowledge diversity more generally rather than insisting on assimilation into a single culture of knowledge generation. One path to preventing the extinction of Indigenous knowledge is its dissemination in classrooms, under Indigenous governance and management (supported by the International Bill of Rights and, specifically in New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi Act 1975 and the Waitangi Tribunal). Not only will this help to protect Indigenous knowledge holders and their culture, it has the potential to generate innovation more broadly.

This is, to me, a lot of hot air that would benefit from the authors giving at least one example. Instead, they insist that New Zealand adhere to the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi, which, gives Māori full rights as British subjects while also stipulating this:

- Article two of the Māori text establishes that Māori will retain full chieftainship over their lands, villages and all their treasures while the English text establishes the continued ownership of the Māori over their lands and establishes the exclusive right of pre-emption of the Crown.

This has been used to buttress the equivalency of MM with modern science, and to justify the two being given equal time in the classroom. But it says no such thing.

The paper ends with a clarion call for “evidence” instead of caricatures (of indigenous knowledge), which is ironic because the paper is almost completely evidence-free, and what evidence it does adduce is distorted. This is expected in a paper designed not to raise up science, but to raise up indigenous people. But the way to do that is to teach them modern science from the get-go, not to coddle their egos by arguing that their traditional “ways of knowing” are complementary rather than inferior to modern science.

In the end, this is not a science paper but a paper inspired (as is so much academic mischief) by DEI. And it ends with a gust of hot air:

Evidence, not caricatures

Indigenous knowledge can complement science-generated knowledge in the pedagogy landscape by providing acceptance and understanding and by contributing to the addressing of global challenges. We urge both education policy analysts and scientists engaging in this debate to draw on evidence rather than caricatures of Indigenous knowledge and a partisan approach to knowledge generation. Knowledge is produced in many traditions. The scientific method is one of those, Indigenous approaches are others, and these are not necessarily mutually exclusive. We need to respect Indigenous knowledge for its inherent value and the philosophical reflections it can provide science to improve outcomes, irrespective of how Indigenous knowledge is contextualized. Much of our time as researchers is spent challenging scientifically derived universal truths through work in local contexts, and Indigenous knowledge does the same but with a higher degree of connectivity between the researcher and what is “researched.” Arguably, the ignorance toward Indigenous knowledge and its application is only slightly greater than ignorance to science methodology. We think this is the strongest rationale for teaching them both in schools.

But there is no evidence to draw on, or at least none is cited in this paper. Tell us some ways that indigenous science has complemented or improved modern science and is in fact not inferior to modern science in producing knowledge! I’m ready to listen! But all we get is lame and probably incorrect claims about “stewardship of the land.” End of story.

In some ways I’m glad I retired, as I don’t have to participate in a system that values knowledge not by its correspondence with reality, but by its correspondence with indigenous “ways of knowing”.

Wouldn’t indigenous knowledge harm and other Denisovan, Neanderthal, Australopithecus, Habilis, and even more hominin cultures?

Look for Critical Indigenous Studies – coming to a university near you – or anywhere fine Critical Studies are sold.

/not-exactly-sarcasm

… Epic post, PCC(E)!

Typo Jerry, “now” not “not” in “… although modern science was developed in the West, it’s not the property of the entire world, …”. Thought I’d point this out since it changes the meaning.

Will fix, thanks.

In Scandinavian universities, there is a lamentable lack of attention to the scientific value of the Indigenous traditions documented in the Norse eddas and sagas. For example, Nordic medical schools never mention the treatment of illness with runic inscriptions on whalebone or wood. And there is no attention to the seidr Way of Knowing, once widely accepted in Norse society, explained below.

“The typical practitioners of seidr were wise-women (volvur or spakonur), who would sit within a magic circle and summon the spirits from whom knowledge could be gained. In the Saga of Erik the Red, a very good description of such a practitioner is preserved. Her name was Thorbjörg. She wore beads around her neck and had a hat of black lambskin. A small bag of magical paraphernalia was attached to her belt. She was reputed to live on kid’s milk, porridge, and the hearts of animals (which were felt to impart understanding). She practised seidr during the night and on this particular occasion, was able to say by the following morning that the famine which had ravaged the land was about to subside.

Just what Thorbjörg had in her magic bag we do not know. However Grøn has called attention to an old Norwegian law from the period just after conversion to Christianity that specifically names “hair, toad feet, and human nails” as used in witchcraft. “

When the savages are so noble, how can you not emulate them?

The authors of the article argue that “…teaching Indigenous knowledge alongside science should not seek to usurp science (in the way that, for example, creationism seeks to undermine evolutionary theory because they are incompatible with one another)….”

Given that there is no “should” in life, you can bet your bippy that many advocates for Indigenous knowledge will indeed seek to usurp science just as creationists continue to do same. There’s a religion to defend!

I had a friend who often belittled the word “should.”

I think “should” does have a place in life. If you want to accomplish something, or if you want to know something, one should do this or that.

What’s the problem with “should” in this context?

We all use the word “should” almost every day. It’s hard to avoid. But “should” is often a command met with a “Who are you to tell me what to do!” attitude. As such, it’s fair to say there is no “should” in life. People do what they feel they gotta do, no matter how stupid the doing is.

This suggested some questions – just to think on the spot about this, I’m not “going after” anyone/thing :

Should water be drunk in order that animals do not dehydrate?

Should heat be produced in order that animals not to freeze to death?

Should wisdom teeth be removed to avoid dental problems?

For each “should” there is a result that is expected. Compare:

Should wisdom teeth be removed?

Should water be drank?

Should heat be produced?

… not sure how that relates if at all to is/ought.

I shoulda coulda…

When I read, Indigenous knowledge is of equal value to modern scientific knowledge, I sense that the deeper meaning, perhaps believed subconsciously, is,

Indigenous people are of equal value to the rest of the population. Fair minded people can agree with the latter. It’s sad to think, of course, that the indigenous feel the need to find a way to express this so indirectly.

I infer other meanings. We used to believe that antibiotic treatment is superior to smudging or the medicine wheel because it works better. The statement that one thing works better than another is now denounced as a “microaggression” against proponents of the second thing. What is rejected is empiricism. We used to describe the empirical movement from primitive ineffective technologies to more effective ones as progress. Remember? But today, the individuals who call themselves “Progressives” are, remarkably, the very ones who deny that progress occurs in knowledge of the world.

“Microaggressions” themselves are made up bs, I think by a Dr. David Su (?), in 2008.

They have no empirical proof or basis. Just something some post-mod woke professor MADE UP. Again, like MM, NOT science.

Yet they’re spoken of like something that IS science.

Object to this every time you see “Microaggression” do the heavy lifting for woke nonsense. I do.

D.A.

NYC

Another detailed post by Jerry that I’ve forwarded to my wife’s son, a chemistry professor.

Recently I decided — for the first time — to vote for office-holders in AAAS. (I’m a subscriber-member in the category of “science advocate.”)

I found it relatively easy to spot the DEI-type statements and vote for the people who spoke only about science. It felt good to vote.

Excellent piece above, PCC(E).

The Waitangi Treaty has NOTHING to do with science. At all.

There is a professor Elizabeth Rata in NZ (U. AKL.) who is pushing back against a lot of the Treaty nonsense, in various areas including the law, history and education.

Excellent interview here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Pn9SZkw7FvQ&t=1000s

Heroine.

D.A.

NYC

Indigenous forms of knowledge were not just inferior to modern science. Compare also the scientific knowledge of the medieval Islamic world, where the sciences flourished during the Golden Age of Islam. The decline that followed has been much studied, and the decline may be ascribed to developments in religion. But indigenous forms of knowledge never matched either modern science or earlier medieval science.

Have you read this?

https://www.thenewatlantis.com/publications/why-the-arabic-world-turned-away-from-science

I often hear the argument that science is just another belief system, suggesting that somehow one is on the same level as the other. Wrong. Science is a system of disbelief – it is incompatible with all belief systems.

Similar to the “atheism is a religion” nonsense we have to put up with too often.

D.A.

NYC

(I’ll shut up now, roolz)

Crazy. After this DEI craze ruins science by creating a morass of confusion, who will be left to rely on in a time of crisis when we actually need scientific expertise? The AAAS seems willing to risk the entire scientific enterprise in the name of political correctness. It’s a dangerous game they play.

Back in the Before Times, about forty years ago, when I studied anthropology in college (I was studying to be an ethnomusicologist, path not taken), we were taught the emic and etic approaches to fieldwork. https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emic_and_etic

At that time, anthropology was pursued as a hard science. The emic approach was incorporated as a necessary counterbalance to the overly etic approach of the social sciences in the past. I disagree with some anthropologists who conceive of the emic and etic as the extremes of a spectrum of study. I conceive the emic as being subsumed under the etic, with the understanding that it would be a poor anthropological study that didn’t account for the emic. Today, though, it appears to be that the pendulum has swung too far to the countervailing extreme with the result that the emic has trounced the etic not only in the social sciences but, as we’re seeing with the controversies surrounding MM and other Indigenous dogmas, in the hard sciences as well. I advocate returning to a balanced approach incorporating the emic and etic in proper relationship to arrive at a cross-cultural body of knowledge, shared by all in the world.

Shame on AAAS! Maybe a way to point out the inanity of MM “science” is to point out how it conflicts with our own indigenous, “First Nations” claims of knowledge and truth in the US.

Whose science is true and for whom? Science is supposed to be objective, true everywhere, and unfettered by cultural relativism, even early culture.

If MM burn some local herb to drive evil spirits out of a location while the Navajo burn sage, let them write a grant for a study designed to determine which is more efficacious. As a grant reviewer, I would insist on them burning bull shit as a negative control. I’m sure Science would publish it.

One last comment, lest I bend Da Roolz too much. I underscore and bring to the fore Jerry’s term “toolkit,” which, of course, is the scientific method. I’m happy that my children learned the SM (not MM 😉) in school and from PBS, viz.,

https://youtu.be/LzGeKJzY5_w?feature=shared

Well it’s a ‘Policy Forum’ article, whatever that means. I don’t know if that means that editors at AAAS necessarily endorse it, beyond maybe publishing it in the spirit that broad points of view ought to be published in forums. Of course I know of the far leftward leanings of some AAAS editors, and so one is right to be suspicious.

The authors are from New Zealand, and I think they are advocating for their point of view in general, not just for the U.S, despite this publication being in an AAAS journal. So I guess N.Z. science is automatically enhanced by MM traditions, while American and European science, as if they were different, would be magically strengthened by Native American and I dunno maybe Norsemen traditions, respectively.

Scientists seek worldwide knowledge. Supernatural explanations, being local, cannot be considered knowledge under worldwide criteria.

“Methodological naturalism” is a term coined by creationists to make it appear that scientists are doing something wrong when all scientists are doing is acting with neutrality by omitting local bias. When the authors of the article speak of a “philosophically different form of knowledge” they play the creationists’ game. Indigenous knowledge, along with “other ways of knowing” and “different epistemologies,” cannot be considered knowledge till it passes the worldwide test of neutrality by discarding local bias.

And yes, science contains bias, but it’s the function of peer review to catch and remove that bias, though it may take decades to do so.

Galileo alone contributed more to physics than all the indigenous cultures that ever existed.

RE: “a lot of hot air”

It is far worse than mere hot air. It is possibly the worst point in the entire article. In the authors’ statement that “this [will] help to protect Indigenous knowledge holders and their culture”, they make clear that one serious concern they have is with the need for ‘protection’ of their MM advocates. Now, that is fundamentally opposed to a modern scientific approach. We do not protect modern scientists from dissent. We do not provide a ‘safe space’ where they are free from challenge. It’s important to see that it is not just the ‘scientific’ concepts and ideas which are important here. The claim in the article is that their people spewing their MM ideas must be made safe in ways in which modern scientists are not. They seriously want their holy men specially protected as holy men within a modern, secular, liberal democracy, — holy, sacred, above any criticism from outside. That is why the authors of the garbage papers you mention will not back down.

There’d be an interesting paper in comparing their expectation of safety-from-challenge with the old business of papal infallibility.

“…while failing thus far to solve the most pressing challenges of our time (such as climate change).”

It is not scientists who are failing to solve climate change. Many sound ideas have come out of scientific research, plus, there is lots of observation underpinning these ideas.

We are failing to address climate change because of RESISTANCE to these solutions, mainly from industries that benefit financially from the status quo.

L

Industries and their willing customers, which is all of us trapped in the collective-action problem. But you are right that it’s not a scientific problem. The scientific question is straightforward since the 1890s: stop emitting greenhouse gases and the earth will almost certainly stop warming eventually. Can’t blame science that not many people are willing to do that, nor are they willing to be compelled to.

An example of Indigenous stewardship of the land is the North American fur trade. While this was fostered by European and North American companies such as the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, that served a voracious market for pelts, it was the Indigenous people who did the trapping, for the trade goods they received in return. As a result of this, the North American beaver was nearly exterminated. There was no coercion here, nor could there have been – these companies dealt with autonomous, scattered groups across a huge expanse of land, and any attempt to force them to go out and trap would have been fruitless and counter-productive.

Real stewardship of the land would have involved conservation of the resource by those who lived on it. But there was none of that.

The beavers who were not quite trapped to extinction would surely be pleased by the following encomium to their species, from a craft gallery on Vancouver Island:

“The Beaver in Native American tradition teaches people to be productive and not limit their options. He teaches us to be persistent and to use available resources. The Beaver helps people understand the dynamics of teamwork and to appreciate each individual’s talents and contributions in order to accomplish anything. He is a builder of the mind, body, and soul and symbolizes creativity, creation, cooperation, persistence and harmony. The Beaver is also a hard worker and will not quit his job until he is done.”

Russian colonization east to Siberia was based on the fur trade also. I’m unsure of the extinction rate, if any. Seems the humans are outnumbered there.

Also northward expansion of Japanese power against the Ainu in Hokkaido was fur driven.

Furries all! (hehhhee!)

Those two expansions, Russian and Japanese, are interesting parts of history.

Despite speaking some (bad) Russian I’ve never been there and in Japan my residence and travels never got much further north than Tokyo. One day.

D.A.

NYC

“Furries all!” I like what you did there, David, the Ainu being among the most hirsute populations of humans.

“Money talks, beaver shite walks.”

In late 2023, New Zealand’s left wing Labour government was replaced, via general election, with a government described here in NZ as centre-right. I suspect that in much of the world it would be described as centrist. It was under the previous Labour government that a new curriculum was being prepared that included the teaching of MM in school science classes. I don’t recall any parties directly campaigning on that issue but there was significant backlash in NZ against a range of Labour policies that many felt were virtue signaling to minorities, wasteful and even undemocratic. I expect the idea of teaching MM as science in NZ is now dead.

So much of what I read in the DEI space reads like chatGPT or other automatic means of production.

Valorization of the indigenous is a facet of deep communism. The Soviets had an almost fetish like obsession with their NE Arctic/Yamal/Kamchatka tribes. Very “noble savage” stuff and wildly patronizing.

NZ is the latest example of this. There is SOME mild push back but it seems to be limited to a few brave souls. Which says something as by necessity of size the NZ intelligencia is small. And their quality is not shared by their shitty mass media where I’ve heard the best brains leave for Australia or the UK leaving the dross to report…. on things like the Maori discovery of Antarctica. (sigh)

D.A.

NYC

I often get the feeling that attempts to water down science by mixing it with religion, spirituality, or indigenous Ways of Knowing are motivated by people who most definitely do want morality, ideology, and advice about how to live infused into science — and everything else, because they believe that developing Good Character is more important than Being Right.

I mean, look at the Big Picture. Be nice, be kind, stop focusing on accurately understanding the world and start working on understanding yourself while you Play Well With Others. How could doing this possibly go wrong?

How could it be menacing?

It’s the ethos of the kindergarten class.

Indeed. By that argument we should recognise ‘the value’ of our Medieval ancestors folk medicine. It was another way of knowing after all.

Look at all the remedies for the Great Pestilence (Black Death). Prayer, breathing fumes of orange and cloves to fight off the miasma, flagellation, Four Thieves Vinegar (this Black Death cure from the Medieval Period mixed vinegar with garlic, herbs, and spices), blood letting, rubbing the buboes with onions. Plus snakes, chickens and leeches applied topically.

I’m unconvinced.

So much indigenous knowledge is limited to a narrow range of scales: they knew nothing about things smaller than an eyelash or larger than a coastline; or about events slower than a few lifetimes or faster than a few seconds. Cosmology, geology, evolution, quantum mechanics, molecular biology, embryology, microbial disease, the ecology of soils, the circulation of the oceans, and pretty much everything else that didn’t involve getting enough to eat and avoiding being killed (not to say colonized or enslaved) by another indigenous group just didn’t enter into indigenous “knowledge”.

But it happens that I teach topics in biology on those narrow and humane temporal and spatial scales. So if I wanted to I could “indigenize” my classroom and “decolonize” my teaching.

The problem is that the associate deans and assistant vice presidents who are pushing this shite at my university don’t want me to teach *all* indigenous knowledge. And they certainly don’t want me to teach Matauranga Mauri. They want me to teach the indigenous knowledge of “the Tsleil-Waututh (səl̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ), Kwikwetlem (kʷikʷəƛ̓əm), Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw) and Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) Nations on whose unceded traditional territories we work and play.”

I refuse to do this because the results are so fucking parochial. About half of my students are not white settler colonialists, and had no hand in the displacement and disenfranchisement of indigenous people 150 years ago. Those students have ~zero interest in what the Tsleil-Waututh (səl̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ), Kwikwetlem (kʷikʷəƛ̓əm), Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw) and Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) Nations thought about animals and ecology and evolution (of which they had approximately no notion). Why should I bore my Chinese, Korean, Indian, Iranian, and Pakistani students with this stuff?

And most of my white settler colonialist students are not going to stay here, including the ones who grew up on conquered Tsleil-Waututh (səl̓ilw̓ətaʔɬ), Kwikwetlem (kʷikʷəƛ̓əm), Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw) and Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) lands. They’re going to other cities & countries where the displaced and conquered indigenous people have a completely different set of myths and ideas about animals and ecology and evolution (a little, sometimes). It’s not Turtle Island all the way down, and teaching my students one set of local parochial myths and “knowledge” is hardly setting them up for success elsewhere. It’s merely teaching them to mouth some platitudes about the wise ewoks who lived here before us, and not rock the woke boat.

Edited to add: my copy-paste of the IPA characters for those indigenous nations is a WordPress tragedy. I can’t be arsed to fix it.

I’d love to get my hands on whoever (probably long dead) persuaded the Coast Salish First Nations Elders to adopt the IPA for their written language. No doubt this has been very convenient for linguists, but it’s a disaster for any hope of local adoption of the indigenous names.

That, Mike (comment #24), is THE best rant I’ve ever read against DEI/Indigenous “ways of knowing”. This stuff is just so pitiful and wrong-headed and, sadly, I don’t think most of us will live long enough to see it end. It’s going to require its rejection by a critical mass of people of the “right” color/ethnicity/minority who aren’t afraid of being associated with the “oppressors”.

This may make me sound like a conspiracy theorist but more and more I feel there is a malicious, deliberate divide and conquer force at work here. Some force that wants us bickering with one another rather than paying attention to the bigger picture. Am I alone in this thinking?

Thanks! I should have added (but comment was too long): my university administrators don’t ask me to teach a “Western” version of animal ecology that’s only based on local scientific knowledge because they know that would be ridiculous. So they’re content with me and my colleagues teaching the usual global synthesis of scientific knowledge.

They ask to teach alongside that a local version of indigenous knowledge for two reasons. One is obvious: this is a bone they want to throw to a marginalized group that includes a lot of individuals who really are suffering. The other goes unstated: it’s impossible to synthesize global indigenous knowledge into a companion for the global synthesis of science because those indigenous knowledges (ha ha) are mutually incompatible. Like the competing metaphysical claims by religions (that Jerry has written about so eloquently), competing epistemological claims by indigenous cultures can’t be reconciled with each other. At least not without some kind of arbiter like the scientific method.

So we get these mismatched efforts to teach science (global, synthetic, approaching truth) alongside indigenous knowledge (local, idiosyncratic, probably mostly wrong but who knows).

Thanks for the explication. Best wishes. I’d drown if I were trying to work in our current environment on campuses.

I feel that the great misstep of Postmodernism is that, in its effort to have voices heard that weren’t old white men, it also professes that all voices are equally valid.

The two idiotic roads this has led us down is the one where we need to listen to a whole load of garbage and the other one where voices with something intelligent to say don’t get enough airtime.

This is a loose-loose situation we’re in and also punishes brilliant non-old-white-males.

Thanks, Postmodernism.

Please, the two idiotic roads you mention are correctly referred to as the Two Row Wampum Belt. For details, consult Concordia University, on the unceded lands of the Société de Notre-Dame de Montréal, which was in turn on the unceded hunting grounds of the Mohawk.

Quinine as an example of indigenous empiric knowledge: even less than meets the eye. It’s not clear if the Incas recognized the disease malaria* and figured out that cinchona bark extract was good for it, or if it was used merely as a non-specific anti-pyretic, like willow bark. If most fevers in your locality are due to malaria, then your bark extract will work by happenstance, if you can give enough active ingredient to the sufferer. It is quite toxic — when better drugs were synthesized by the scientifically based chemical industry, quinine disappeared from use until resistance to these later drugs resuscitated its use in severe cases today. Publication of information about its use was entirely a European phenomenon thanks to writing and the sea-going ships that brought these literate observers to Peru in the first place.

The larger issue is that it was modern science that figured out what malaria was and what was in cinchona bark that made it work, and where it wouldn’t. Instead of giving it to everyone with fever, you give it, and its later replacements, only to people with fever who have malaria parasites visible in their blood cells. Then when you figure out the role of the mosquito in the parasite’s life cycle you have other avenues to prevent transmission, nets, DDT, vaccine development, and all that. I could imagine a primitive shaman doing a controlled trial of some empiric remedy if his culture allowed that kind of testing of beliefs. (And “slam-bang” effects don’t require controlled trials at all.) What I can’t see is his examining blood for malaria parasites and figuring out they caused the disease when his culture had never produced glass or metalworking to fashion a microscope with. Technology enables science as much as the reverse.

—————

* Established vivax malaria has a day on day off fever pattern but there aren’t written records to know if the Incas knew that and used cinchona bark specifically for this so called “tertian fever” long known in Europe.

Perhaps the offering of a few thousand still beating human hearts will make things better. It is indigenous knowledge when all said and done.

IMHO “Faith vs Fact”, the battle cry of secularization is a false dichotomy that puts too much value on science, which is already showing cracks in the intersection with politics. Anyone who looks into the foundations of mathematics like David Hilbert’s program to put math on a firm rational basis (It wasn’t, see Godel et al) or the problems with quantum mechanics (which is what the cat thought experiment is all about, sorry Einstein, Hawkings said effectively God does play dice with the universe) will find that rationality comes down to faith also – one that reveals a lot of useful truths about objective reality indeed, and creates a lot of technical ‘know how’ but what morality people have (survival of the fittest, like Russia, China or North Korea) that determines what they do with that know how, like how to build bigger bombs, create a high standard of living at environmental expense, etc. Anyway the secularization push since the Enlightement and US & French revolutions is creating this generation of highly secularized people so we’re seeing how that works out 🙂 I heard the same Faith -vs- Fact statement from Sheldon on Netflix the other night, don’t worry, it’s big in the social media popular mind and should overrun the old boomer rust bowl sticks in the mud, unless there is some kind of tech crash like in 1983 or 2000.

You mischaracterize Hilbert’s program which “…calls for a formalization of all of mathematics in axiomatic form, together with a proof that this axiomatization of mathematics is consistent. The consistency proof itself was to be carried out using only what Hilbert called “finitary” methods.” (https://plato.stanford.edu/Entries/hilbert-program/)

It can’t work, as Godel showed, but that’s a far cry from failing to be “rational”.

Even if everything Chuck wrote is true, and we have too much confidence in rationality and in our scientific understanding of the world, he still gives no reason why we should put more confidence in a religious understanding of the world. Which religion? Why should we accept it? How should we reconcile its metaphysical claims with those of other religions? This is a non-criticism of science and rationality.

I’m all in favour of teaching indigenous science here in the UK. Give the Welsh and the Cornish their due, I say.

*bangs head against wall in flabbergasted frustration*