This article by Erec Smith was first published in the Boston Globe, where you can find an archived link here, but has also been published unpaywalled by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank where author Erec Smith is a research fellow (he’s also “an associate professor of rhetoric and composition at York College of Pennsylvania, and cofounder of Free Black Thought”).

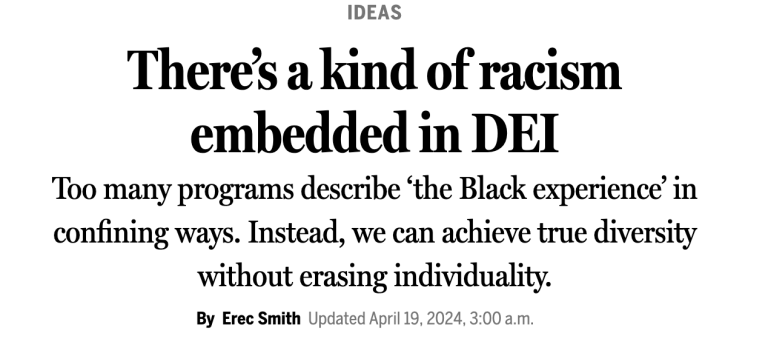

Smith’s thesis is that DEI is racist because it rests on prescribing “approved ways” that black people should behave and think, ways that he instantiates by giving two quotes. The first is a now-deleted tweet by Nikole Hannah-Jones:

And from President Biden:

“If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, you ain’t Black.”

That, says Smith, is “a statement that implicitly prescribes how Black voters should think.”

Smith developed this take because as a black kid in a white school he was expected to “act black,” yet when he moved to a mostly black school he was criticized for “acting white”—speaking “white English” and so on. DEI, he avers, practices “prescriptive racism” by expecting black people to have the opinions that other “progressive” black people have, so that there is an approved and proper way of Thinking While Black promoted by DEI. Smith also criticizes right-wing racists for their past practice of criticizing “uppity Negroes” who didn’t act like black people should, though we don’t see much of that these days.

When Smith got to college and then became a faculty member, he saw this same tendency in DEI, except that the “uppity Negroes” are now those blacks who don’t conform to the prescribed progressive ideology. You can think of some “uppity” blacks, including people like John McWhorter, Glenn Loury, Coleman Hughes, and Thomas Sowell, all worth reading or listening to.

Click to read:

I’ll give a few excerpts:

Unlike traditional racism — the belief that particular races are, in some way, inherently inferior to others — prescriptive racism dictates how a person should behave. That is, an identity type is prescribed to a group of people, and any individual who skirts that prescription is deemed inauthentic or even defective. President Biden displayed prescriptive racism when he said “If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, you ain’t Black,” a statement that implicitly prescribes how Black voters should think.

. . .prescriptive racism casts a broader net, disadvantaging people for not abiding by a long list of things a Black person shouldn’t do. A prescriptive racist may not mind that a Black person has a master’s degree, but he may scoff at the sight of a Black man watching the Masters — especially if Tiger isn’t playing. A white prescriptive racist would look at a Black person speaking standard English the way a Black person would look at a white person wearing a dashiki. Lest you think that last statement is mere speculation, I have met several people who have voiced derision and irritation upon hearing standard English come out of my mouth. My use of language was an affront to their expectations and sensibilities.

Many prescriptive racists are often people of the same minority group. A Black person lambasting another Black person for acting in ways deemed racially inauthentic — for example, speaking in dialects coded “white” — is engaging in prescriptive racism.

And how it enters DEI:

And prescriptive racism is not just a social phenomenon; it is now being institutionalized. More and more, it is erroneously labeled diversity, equity, and inclusion, and it is winning out over initiatives more in line with the civil rights movement and classical liberal values like individuality, free speech, reason, and even equality. It is becoming policy in academia, corporate America, and even the military. To put it another way, contemporary DEI is prescriptive racism.

In academia, I’ve found, Blackness is a role, a “pre‐script,” to which Black people are expected to conform if they want to be accepted or, sometimes, acknowledged at all. A Black scholar cannot simply study and write about Plato; she has to write about Plato from a Black perspective. Nobody shows much interest in a Black graduate student drafting a dissertation on American Transcendentalism that isn’t focused on its relevance to the Black experience. In this sense, applying for graduate school or a professorship is akin to auditioning for “Black person” in some live‐action role‐playing event.

I hadn’t realized the expectations outlined in the second paragraph, but I’m sure they’re true, for nearly every black academic I know of is engaged in writing about the connection between their discipline and “blackness”. (This also applies to “studies” programs, in which white people also conform to DEI expectations by imbuing scholarship with ideology approved by DEI.) What is clear is that DEI is racist in expecting groups to behave in certain approved ways and to hold certain approved views. John McWhorter, for instance, has not done that, and he’s suffered for it. As he says, he’ll never be invited to another linguistics meeting nor get an invitation to speak about linguistics at another university. What a pity for such a smart guy! But that’s what you suffer for thinking independently—for being “heterodox.”

One more quote on “political blackness”:

Political Blackness made much more sense several decades ago. Both Malcolm X and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. could have been construed as politically Black. Why? Because, when these men lived, whether Black Americans were gay or straight, Islamic or Christian, working class or middle class, none of them could sit at the front of the bus in the Jim Crow South. However, in this third decade of the 21st century, the efficacy of political Blackness has waned significantly. Though things are not perfect and racist environments still exist, policy changes have afforded Black Americans opportunities and resources traditionally denied them. As a result, “the Black experience” has become so varied that the use of “the” is questionable.

The idea of an indefinite abject oppression that justifies essentialism and political Blackness does not reflect reality. The facts that roughly 80 percent of Black Americans are working class or higher and that the number of Black immigrants has skyrocketed (strongly suggesting that the United States isn’t a fundamentally anti‐Black country) are just two of many things that illustrate this. But activists who still want power must fabricate an insidious specter of oppression, and an essential victimhood has to be prescribed, whether they are homeless or Oprah Winfrey. If you are a Black American who does not abide by this prescription, be you liberal or conservative, you are seen as weakening the political power of Black Americans.

The inherent paradox of contemporary social justice is the essentialism that says “you are bad if you stereotype other people, but you are also bad if you don’t.”

Smith goes on to say that he and others have founded a new organization to combat prescriptive racism:

I and a few others have cofounded Free Black Thought, a nonprofit newsletter and podcast representing “the rich diversity of Black thought beyond the narrow spectrum of views promoted by mainstream outlets as defining ‘the Black perspective.’” We come from a classical liberal standpoint, meaning we believe people should be treated as sovereign individuals and not deindividuated members of a group. In other words, we’re sticking it to the prescriptive racists.

The “free” in Free Black Thought is both an adjective and a verb. We want to promote thought free from the tyranny of prescription, which means we publish and promote a wide array of ideological points and artistic expression, highlighting Black artists and thinkers typically neglected in mainstream media. But we also seek “to free” Black thought by offering alternatives to K‑12 curricula informed by critical social justice, like BLM in Schools and Woke Kindergarten, to let schools know that other ways to promote true DEI do exist.

Another sin laid at the door of DEI, which I’m hoping is on the way out. Note that I said “hoping”, not “predicting.”