by Greg Mayer

While Jerry’s traveling, I thought it would be a good time to post the second installment of southern trees. In the first, I showed mostly the epiphytes that grow on trees, and now it will be the trees themselves.

The northeastern US– roughly around the Great Lakes, New England, and the mid-Atlantic– is dominated by broad-leaved, deciduous, hardwood forests (think oaks, maples, hickories), grading to evergreen coniferous forest to the north, tall grass prairie to the west, and southern forest to the south. Interestingly, a big swath of the American south, like the far north, is dominated by coniferous forest: very tall pines, with a short, shrubby understory. As you get far enough south, the understory becomes palms.

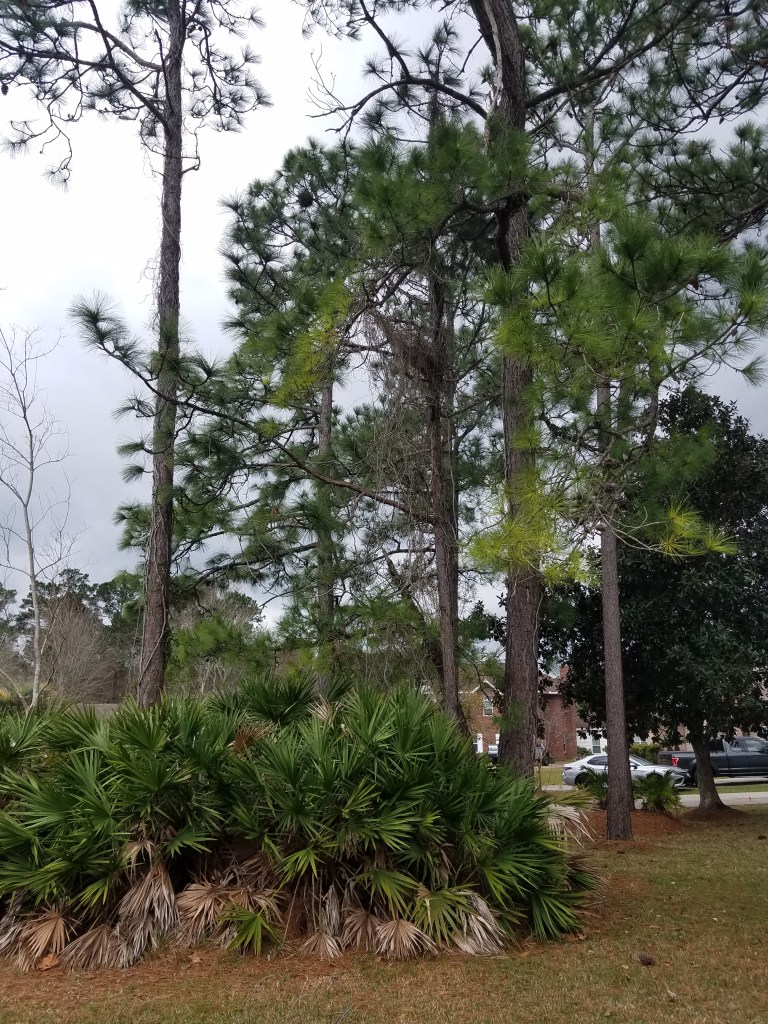

The above photo is of a suburban front yard, but as either a remnant of the pre-development forest, or as a planted recreation, it gives a fair impression of a tiny bit of this southern conifer forest. We see about five pines, a thick palmetto (?Sabal sp.) understory, and to the left front and right background, two broad-leaved trees, deciduous on the left, evergreen on the right.

The pines have very long needles, many over a foot long, and longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) is one of the characteristic species. But there are several other pines with long needles, and I’ve never been able to convince myself that I can tell them apart. I think there are two species in this little stand, one with short cones and the other with long cones.

But cones vary both within a tree, related to age and cone-specific effects, and among trees of the same species, so I’m not sure. Here’s some of the range of variation in the long cones:

and among the short cones:

Many of the long cones were damaged, the scales being torn or chewed off. I’m not sure what does this, or why. Gray squirrels (Sciurus carolinensis) are common at this site, but I don’t think pine cone scales are edible or nutritious.

There also seemed to be differences in the bark. The short cone pine has a more blocky texture to the bark:

While the long cone pine had longer, more flattened ridges; but, again, I’m not sure how much individual variation there is within species.

The broad-leaved trees included evergreen magnolias (Magnolia sp.):

with loads of their seed pods nearby. These pods were not under the magnolia, but over a fence and under one of the pines, so must have been moved– by squirrels?

This is the live oak of some sort (Quercus sp.) from my epiphyte post. Astute readers were able to identify the clumps of leaves higher in the tree as mistletoe.

The tree had lost most of its leaves, but still had some, including non-lobed, “live oaky” leaves”:

and slightly-lobed, much more, at least to a northerner, “oaky” leaves:

We’ll finish with the red maple (Acer rubrum) a tree I am very familiar with from the north, that in Florida seems to be semi-deciduous– losing most, but not all of its leaves in the winter. This row of trees is clearly planted:

And, though mostly leafless, there were some leaves still on the trees:

As with the previous post on this, please weigh in with plant identifications!

This is a nice follow up!

I really get a kick out of the fact that pine cones can open or close in different humidity / conditions – e.g. if one is brought indoors, it can change it’s shape / envelope. This can be explored a bit, very easily.

Beat me to it.

Yes, but i don’t get the point of the 4 cones from same tree picture – they seem very similar in size but only different in state of openess as flowers from same plant might be.

Pine species hybridize easily and frequently, It may be impossible to correctly identify a tree to species of Quercus.

I have observed squirrels eating the seeds from pine cones by tearing the scales from the cones and spitting them to the ground. The squirrels left the ground under trees with ripe cones covered with destroyed and unripe cones. (Jacksonville, Texas)

Seen the same in southern louisiana

Great pictures. I am reminded, yet again, to our shame, how much of our original forest cover we have lost in the UK.

Stripped cones: crossbills?

Well, yes. But we did strip the original growth forests back in the Neolithic, as the “farming package” from the continent was adopted and land cleared for agriculture. For the 4000 years since then the forests have receded and advanced (under differing degrees of management) repeatedly. There are probably records of Roman administrators bemoaning the Britonculi and their poor forest management.

We had a national bout of concern over timber management when board for shoring trenches in WW1 was in short supply : consequence – the tax structures that have coated the hillsides in almost sterile monocultures of fast-growing conifers. (The prospect of not having the material for a human hecatomb was not acceptable.) We had another, worrying about timber for the navy, in the 16th & 17 centuries (with a side effect of requiring all farmers above a certain acreage to plant a minimum area of hemp – for rope (the species name “cannabis” as an indicator of rope-making fibres was discussed here recently). There was a spreading of forests in the population decrease following the Black Death – but that didn’t last very long.

Complaining about forest cover was a popular topic of conversation under Guillame Le Bâtard (a.k.a. William 1) – so he set aside a considerable amount of land as “royal forests” – though hunting and Saxon-control was probably more of an issue than the timber resource per se. A navy wasn’t really a big strategic concern for the Norman invaders.

An experiment that I enjoy watching directly are the results of is the hecatomb of sheep and deer on the highlands of the Cairngorms National Nature Reserve. Spreading from the few remaining pockets of “natural” Caledonian pine forest in the NNR, we’re seeing far more seedlings sticking up through the heather – and not getting immediately eaten by a deer or sheep. Already the bare mountainsides are starting to get a bit fuzzy as the trees are coming back. Of course, that’s very labile – a change in government policy, or a shift of policy-making back abroad, could see the huntin’ shootin’ fishin’ brigade come back in greater numbers. Though if the wolf-people get their plan to re-introduce the wolf in effect, maybe the HSF will remain scared down to the (utterly artificial) grouse moors of the Pennines.

Interesting post, Greg!

I grew up in upstate New York, where deciduous trees dominated. Then I lived for a number of years in the valley and ridge province of the Appalachians at an elevation of about 2000 feet. The flora there was very different from upstate New York! The deciduous trees were oak and hickory, with large maples being a minor component, unlike in New York. And in Virginia, pines were indeed abundant. On our property in Giles County we had mostly Pitch Pines (Pinus rigida). White Pines were seen only occasionally in our area. A bit further south, the Pitch Pines were joined by Loblolly Pines (Pinus taeda). Both are shallowly rooted and prone to pulling out of the ground in storms. (Two Pitch Pines fell on my wife’s car during an ice storm in 1991 and almost destroyed it. We were cowering in the house and watched it happen.) It’s easy to tell the Pitch and Loblolly species apart, but that’s not the case for some of the more scrubby pines we encountered, such as the Virginia pine (Pinus virginiana). From what I understand it takes significant expertise to tell the various pines apart.

On Long Island, NY, where I grew up, and in at least some other more northern parts of the US, red, white, and pitch pines can be readily distinguished. There seem to be more species, and more morphologically similar species, as you head south.

GCM

Loblolly pines seem to strictly adhere to the coastal plain. In Giles county you would have pitch, shortleaf, Virginia, table mountain, and white pines. Virginia (2 needles) and table mountain pines (2-3 needles and prickly cones) have shorter needles than the others. Sorry to be a smart ass.

Being a northerner (Ottawa, Canada) I am familiar with what we know as “Oak” trees. Large, old, heavy deeply lobed green leaves that turn golden brown in tbe fall and are the last of the deciduous leaves to come down in the fall before the snow. I would like to know what is a “live oak”. Is that a different species altogether?

I thought it was just one species, “Live Oak” but it is apparently several species. They’ll grow at least as far N as Williamsburg VA, since there are a number of them around the Wren Bldg, but they’re more likely not seen in the wild till you get down into coastal N Carolina.

In eastern Canada and the northeastern US, there are a number of species of oaks, some common, some rare, but most or all fall into one of two species groups– red oaks, whose lobes are bristle-tipped; and white oaks, whose lobes lack bristles. The red oak group includes red, pin, and black oaks. The white oak group includes white, burr, and swamp white oaks. Both groups should be found around Ottawa, and are the lobed, deciduous oaks you describe.

Live oaks are another group of several species of oaks that have unlobed leaves with what are called entire margins– no lobes, teeth, serrations, etc. I’m not sure if live oaks are a taxonomic group, or just a vernacular term for oaks with this kind of leaf. They tend to be evergreen. I’ve seen them in California (where most or all of the oaks I’ve seem were live oaks of some sort) and in the south (Mississippi, Florida, etc.), where “regular” oaks are also frequently encountered. To northerners (and Canadians, I suppose), live oaks are weird, and don’t seem to be oaks at all, until you notice the acorns. Some live oak leaves are slightly lobed, like the leaf pictured, on which bristles can also be seen.

GCM

Here in the Maritimes (NS) on our property we have quite a selection of deciduous and evergreen, lots of Birch, Spruce, Maple and my favourites, Hemlock, some of our Hemlock are more than 100 years old and have survived as we live in a small valley with a brook running through and this has protected the big trees from the worst of the winds including many hurricanes. So far they are free of the “Wooly Adelgid” which is affecting a lot of these beautiful old trees. We also have a number of willow which grow well because of the proximity of the brook and natural drainage, however they are big favourites of the beavers which we also have and I have protected some with wire fences. One quite large willow is regularly cropped but surprisingly survives and renews I call it Beaver pollarding and we love to see this iconic symbol of Canada particularly with their young and the call of the Beaver is so unique who could resist losing some trees, there are plenty to go around.

An aside about live oaks: Walt Whitman has a poem “I saw in Louisiana a Live-oak Growing” in which he says it “was uttering joyous leaves of dark green.” I like the idea of trees uttering leaves, and that the leaves are joyous. The poem is really nice for other reasons too.

Was sorry there was no picture of the leaf of a Sycamore. So large it would only take one for Adam’s loin cloth.

I did see fallen sycamore leaves, but not the trees from which they had come.

GCM

That magnolia is most likely Magnolia grandiflora. I have a couple in my yard near Pittsburgh, planted by my predecessor who loved magnolias. They’re not supposed to survive this far N, but they’ve soldiered on for the last 30+yrs.

A deciduous magnolia that he also planted is a Magnolia acuminata aka “Cucumber tree.” Fun factoid with them is that in the Victorian era, when exotic magnolias were being discovered elsewhere, they’d be grafted to cucumber tree rootstock and were then popular plantings at cemeteries.

Either in short order or eventually, those grafts mostly failed, and were replaced by cucumber tree shoots from the roots, So it is apparently relatively common to find lone cucumber trees in old cemeteries. There’s one near me, which may be what’s pollinating my tree, since they don’t self-pollinate.

Great post, Greg! I am a dendrophile and enjoy learning about trees. Thank you!

I live in NY state bordering VT, about halfway up. One day I was walking in the village and looking down I saw a tulip tree leaf. I didn’t think they grew this far north. I picked it up and said aloud “This is from a Tulip tree” A passerby got a little nervous, guy talking to leaves and made a comment and left hurriedly. I looked across the street and saw the tree the leaf had come from. It wasn’t like the huge ones I used to see all over DC. It was part of a floral display and they have since removed it, unfortunately.

Upstate NY is mostly north of the range of tulip trees, though they can be common further south in NY (e.g. Long Island, part of the coastal plain), but not as common as even further south– I’ve been in tulip tree forests in Maryland. Outside their native range, I have seen planted tulip trees that survived in Massachusetts and Wisconsin. The Wisconsin ones seem to have reproduced, but I would not say they have become naturalized.

GCM

There are planted tulip trees in the Los Angeles area.

Thank you! This educational post reminded me of tree ID questions I’ve been meaning to study up on…..

Weren’t “magnolia” (in a loose sense) some of the very earliest angiosperms to leave a fossil trace, in the …. mid-Cretaceous (?, say 100 Myr ago). I seem to remember the palynology (resistant organic debris, including pollen in particular) lecturers saying that pollen identifiable as various genera of angiosperms was found for a good few million years before then (they’re tough fossils), but leaf or flower/ seed structure fossils took a while to become common enough to notice.

I got curious if pollen and palynology share a root, but they don’t. Pollen is Latin, pollen (fine powder) and palynology comes from Greek palunein, to sprinkle.

And then not to be confused with palinology – study of female politicians refractive to intelectual discourse, a field currently focused on Bobert and MTG.

The “sprinkle” derivation of “palynology” is appropriate. By the time you’ve disaggregated your sample with acid+hydrogen peroxide (the bubble production really helps with separating clay grain from silica from organic particles), then floated-off the organics, what remains is indeed, a “sprinkle” of dark-brown to black fragments which you can float onto a microscope slide to produce a 1-grain thick preparation for examination.

Pollen grain analysis is a field within palynology – and an important one. But your palynological preparation may also include (but not limited to) organic tests of foraminifera and a lot of other phyla of microbes ; fragments of plant (leaves, stems, roots) ; charcoal (wildfire frequency has changed a lot over the geological record) … all sorts of other stuff.

A palynologist covers a wide range of disciplines. Very often the samples collected at the wellsite will go through several other hands offsite before the final report is complete and a date estimate is available. And an environmental diagnosis, if that was also requested.

The specialism is also used – a lot – in archaeology. It can be very sensitive for environmental diagnoses, especially if recent enough that the specimens found have identifiable modern analogues.

Any resemblance between fine organic sludge and Sarah Palin is purely accidental. I wouldn’t denigrate fine organic sludge with the comparison.

Southern trees better keep your head

Don’t forget what your good book said