Over 100 universities have adopted some version of the University of Chicago’s Principle of Free Expression, also called the “Chicago Statement”: a strong version of free speech, pretty much adhering to the First Amendment. But the same doesn’t hold for another mainstay of our free-speech program: the Kalven Principles. This is the principle of institutional neutrality: that the University is, with very few exceptions, to make no public statement about politics, ideology, or morality. (The exceptions involve issues which directly affect the mission and workings of the University.)

“Kalven,” as we call it, is an important part of ensuring free expression, for it avoids “chilling” our community’s speech by avoiding official positions that might inhibit opponents from expressing themselves. For example, any statement taking a position on the Mideast War, if it were to come from the President of the University or from a department, might inhibit junior professors or students from arguing contrary positions for fear of losing their job, angering their department, or losing tenure. Thus our statement on the Mideast war is lean and anodyne, merely saying that it might cause people difficulties and giving a list of resources for help.

Kalven holds not just for the administration, like deans, the President, and the Provost, but for all official units of the University, including departments. (Note that, as expected, faculty and students are encouraged to excercise freedom of speech as individuals, or even as unofficial groups, so long as they don’t express an “official” university position.) Likewise, our investments are kept secret from the community so that people can’t demand that we take a political position on how the University endowment is handled.

Although some units can’t seem to avoid trying to make Kalven-violating statements, they are prohibited from doing so officially, and it’s worked pretty well. People speak freely and we don’t get in the Congressional trouble that Penn, Harvard, and MIT did. (Had they adhered to a Kalven statement instead of sometimes making political statements and sometimes avoiding them, their waffling wouldn’t have caused such a fracas.) In contrast, we got in no trouble because we hardly make any statements about anything. Ergo we’ve lost no donors, for all potential donors know that we’re not going to take positions that will anger them.

Why, then, have only a few universities followed our Kalven principles while over 100 have followed our free expression principles? After all, they are mutually reinforcing: both parts of a unified program to keep expression free and flowing. The only universities that have adopted Kalven-esque principles, besides us, number two: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and Vanderbilt University. (Vanderbilt’s Chancellor, Daniel Diermeier, is a free-speech advocate who was Provost here before he moved south.) Some professors at Northwestern University have urged adoption of institutional neutrality, but so far little seems to have happened.

Why have universities resisted institutional neutrality? I think it’s because some people, in or out of a university, think that it’s immoral for an institution of higher learning not to weigh in on politics or ideology if they think the “moral” position is clear. During the Red Scare of the Fifties, the University held to institutional neutrality despite calls for us to denounce communism and fire communist professors (this was before Kalven, but the principle, though uncodified, began with president Robert Maynard Hutchins). It seemed clear to many at the time that Communism was bad, but of course not to everyone, and taking an anti-Communist stand would simply inhibit discussion. Try to think of any political position that can be held by a University without potentially inhibiting speech!

But I digress. I want to note that another university has just joined the three having official institutional neutrality. And that is Columbia University, as I learned from this announcement:

From the Columbia Academic Freedom Council:

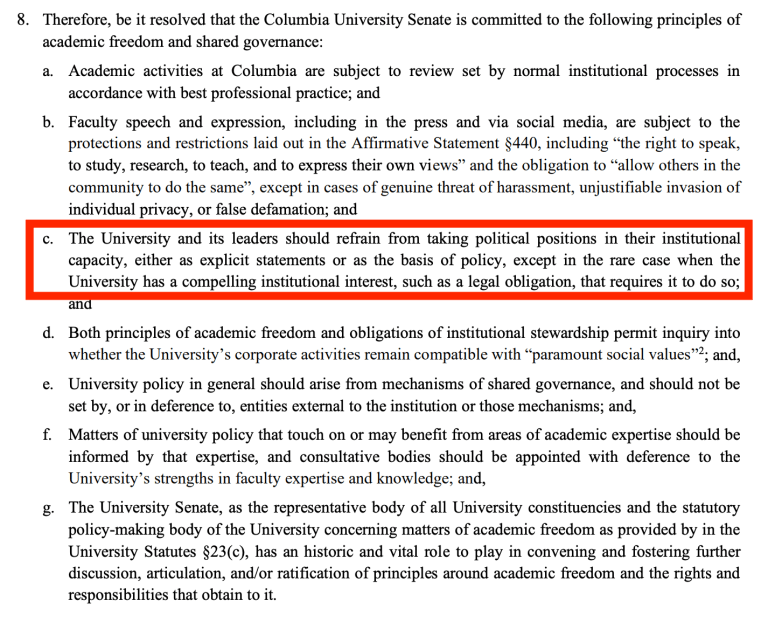

The Columbia University Senate today passed a resolution for the University to adhere to a standard of institutional neutrality as envisioned by the Kalven Committee. The specific language is attached and is as follows:The University and its leaders should refrain from taking political positions in their institutional capacity, either as explicit statements or as the basis of policy, except in the rare case when the University has a compelling institutional interest, such as a legal obligation, that requires it to do so.This language heavily mirrors the language on our Statement of Responsibilities.

Now this isn’t yet perfect, but it’s very close to Kalven. Columbia still needs to clarify what they mean by “The University and its leaders”. Do departments count? Presumably. What about other units, like Museums and the like? We enforce Kalven for them, too, but that was clarified only through challenges.

Finally, (d) is unclear. What does it mean to “permit inquiry into whether the University’s corporate activities remain compatible with paramount social values”? What are those values? Does this mean that the University can take political positions on investments (“corporate activities”)? That needs clarification.

Still, this was adopted by Columbia’s University Senate, and it’s a good start.

I’m not sure if this new principle applies to Barnard College, which is affiliated with Columbia University but still somewhat independent. Still, surely Barnard should follow Columbia by adopting institutional neutrality. If it does, it wouldn’t be able to make statements like the following, which is a clear violation of institutional neutrality. I won’t go into detail why it does violate neutrality, but such a statement would be prohibited at the university of Chicago. This one is from Barnard’s Africana Studies Department. Click to read, and if you see the problem affecting free speech here, put it in the comments:

I haven’t prowled Columbia’s website looking for violations, but this site came into my hands via a reader.

Another thing Columbia needs to do, which caused a bit of an issue here, is how, exactly, violations of institutional neutrality will be reported, adjudicated, and dealt with. Still, all universities should take heed. The benefits of institutional neutrality far outweigh its few problems.

At many (most?) universities, the faculty Senate does not have the authority to enact such a policy. I don’t know about Columbia, but I suspect some further authority there would need to accept or endorse the Senate action.

(As the Secretary of the Faculty at my own institution, I am a student of university governance procedures.)

GCM

Columbia’s faculty senate seems to be pretty empowered:

https://secretary.columbia.edu/sites/default/files/content/University%20Statutes_January2022.pdf

“Unless Trustee concurrence is required, acts of the University Senate under Sections 22 and 23 shall become final on passage. In all matters involving a change in budgetary appropriations, involving the acquisition or disposition of real property, affecting contractual obligations of the University, or as required by law, such concurrence shall be required. In all other matters, the action of the University Senate will be final unless the President shall advise the University Senate not later than its next regularly scheduled meeting that Trustee concurrence is necessary.”

I’ve reviewed a bit of Columbia’s charter and statutes, and the Senate does seem to have considerable authority– good on them! However, without knowing how these statutes have been interpreted and applied (the “common law” of practice and experience), I can’t say for sure how much the adopted resolution is definitive.

GCM

Great news

Regarding the benefits of institutional neutrality:

As Jerry writes, one of them is that it mostly insulates universities from political attacks.

Recently in the news:

Florida Eliminates Sociology as a Core Course at Its Universities. New York Times, Jan 24, 2024

In December, Florida’s education commissioner wrote that “sociology has been hijacked by left-wing activists.”

https://archive.is/OEiqz

Jukka Savolainen: Florida’s Shunning of Sociology Should Be a Wake-Up Call. Wall Street Journal, Dec. 7, 2023

The field has morphed from scientific study into academic advocacy for left-wing causes.

https://archive.is/XIktH

Mr. Savolainen is a professor of sociology at Wayne State University (Detroit, Michigan).

The academic fields where political diversity is minimal are: anthropology and sociology, communications, social work, and gender & queer studies (closely followed by various other ethnic studies).

As Jonathan Haidt put it at the Academic Freedom Conference (Stanford University, November 4 & 5, 2022):

https://youtu.be/KIsN71aTICA?si=rrsjwBGFtzMzGj31&t=950

It was the UNC’s Board of Trustees, rather than its faculty, which adopted the Chicago principles of institutional neutrality. As of 18 months ago, this had not much reduced the widespread rule of DEI doctrine, particularly in the schools of medicine and public health, and in some individual departments (https://www.city-journal.org/article/which-way-for-chapel-hill ). If the Columbia Senate’s new resolution is a hopeful straw in the wind, we look forward to more such resolutions by faculty senates, and maybe by admins.

I could not find a clickable link to the Faculty Statement, but Googled it. There is not even a pretense of neutrality; they are the moral and just, teaching others to join them on the right side of history.

I noticed the statement was on behalf of faculty and administrators. Is it the norm to include the administration? I really don’t know.

Which faculty statement are you talking about (there are 2 in this article)? The Barnard one? If so, then I agree.

Yes, the one from Barnard’s Africana Studies Faculty.

It’s fixed now. Usually departmental statements are just from the department, which doesn’t include the administration but does include chairs. I think in this case they means perhaps a chair and vice-chair, but it could also include staff, though I’ve never seen staff as signers of such a statement.

Claremont McKenna has also endorsed the Kalven Report:

https://www.cmc.edu/free-expression/institutional-nonpartisanship